A Brief History of Time: Audemars Piguet’s Complete Brand History — Part One: 1875–1967

If someone were to ask you to name the watch world’s most famous one-trick pony, how many of you would answer, “Audemars Piguet?” To be honest, until just a few weeks ago, I would probably have been one of those people. As a collector with a modest budget, historically, I always had a tendency to learn mostly about brands I could actually afford. Because of this, I had remained ignorant of Audemars Piguet for far too long. And what a mistake that was.

Sure, looking at the current catalog alone, it could seem like there’s nothing much to brand other than the Royal Oak. However, while you wouldn’t be totally unjustified to make that assumption (just mostly), everybody knows what happens when you assume. When tasked to look into the history of the brand, little did I know just how much I had actually been missing!

The history of Audemars Piguet is a long and illustrious one. Indeed, it is one marked by both insane horological achievements and revolutionary ventures that have shaped the industry to this day. So, I hope you’ll join me in the first of another two-part installment of A Brief History of Time. Today, we’ll discover some of the greatest moments and watches in the history of a true timekeeping titan, Audemars Piguet.

The early days

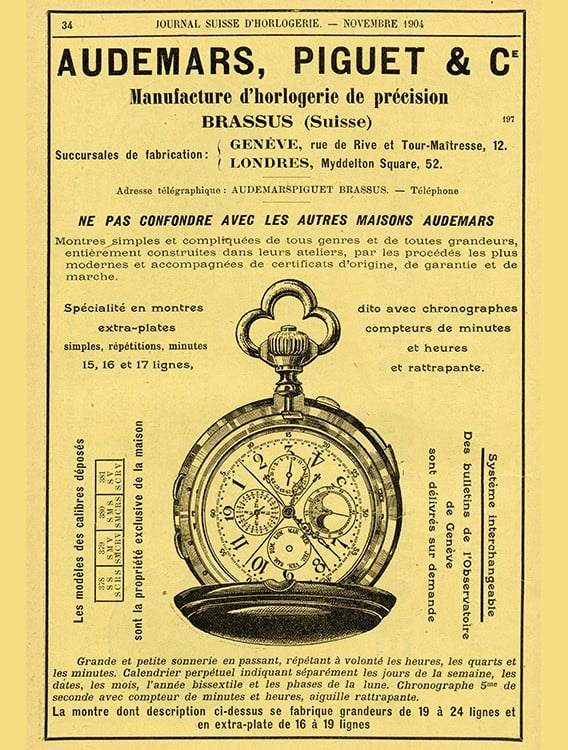

In 1875, 24-year-old Jules-Louis Audemars and his friend, 22-year-old Edward-Auguste Piguet, first joined forces. The pair established their first watchmaking workshop on the Audemars family farm in their hometown of Le Brassus, Switzerland. This small town in the Valleé-de-Joux remains the home of the brand to this day. Both men were professional watchmakers. Audemars specialized in the manufacturing of complicated movements, and Piguet was particularly adept at regulating them. In 1881, the duo officially registered their business as Audemars Piguet & Cie., Manufacture d’Horlogerie. It turns out that Piguet also had a particular knack for business, so the duo split responsibilities. Audemars would lead production, and Piguet would become head of sales and management.

The technical mastery that Jules Audemars displayed even in his younger years cannot be overstated. Even prior to joining with Piguet in 1875, Audemars had already produced a truly amazing horological opus. Created as a sort of “graduation project” for watchmaking school, the young master had presented an incredible, complicated pocket watch. It featured not only a perpetual calendar with day, date, 48-month, and moonphase displays, but also dead beat seconds and a quarter repeater complication. This was an amazing accomplishment for someone so young and just finishing his education at watchmaking school.

Springing off the back of this creation, Audemars Piguet immediately set to work producing complicated pocket watches. It wasted no time at all in establishing itself as the go-to specialist in this field. In addition to making its own watches, Audemars Piguet also produced movements for brands that lacked the expertise to realize their horological visions.

Audemars Piguet becomes an international brand

With Audemars steadily building his reputation as a master horologist, Piguet focused on the company’s expansion. While remaining headquartered in Le Brassus, Piguet also opened a workshop in Geneva in 1885. This allowed the brand to be closer to many of its end clients. Geneva also served as a more suitable hub for European and international distribution. In 1888, Piguet opened another branch in London. One year later, Audemars Piguet increased its international presence even further, establishing branches in New York, Buenos Aires, Berlin, and Paris.

Incredible feats of horology

By 1889, Audemars Piguet had also already begun authoring what would become an impressive list of world firsts. That year, Audemars Piguet presented the first wristwatch movement with a minute repeater complication. Even in those days, the industry relied heavily on collaboration. Audemars Piguet built the movement on commission by Louis Brandt (later Omega), with his own complication atop a LeCoultre ébauche. Housed in a 35mm 18k gold case with an actuating lever at three o’clock, the watch was presented as a finished product by Louis Brandt in 1892. It resides in the Omega museum today.

Rounding out the 19th century, Audemars Piguet reached another brand milestone by producing its most complex watch thus far. While the brand had already produced its first grand complication pocket watch in 1882, it had featured “only” a chronograph, split-seconds hand, minute repeater, and a perpetual calendar. In 1899, AP took that creation took that to the next level. The latest watch featured a head-spinning array of complications: grande and petite sonnerie for chiming hours and quarters automatically, a repeater for chiming hours, quarters, and minutes on command, dead beat seconds, alarm, perpetual calendar, chronograph with jumping seconds, and a split-seconds hand. The brand presented this incredible creation at the World Fair in Paris in 1899. Union Glashütte then bought the movement, cased it, and sold it as the Universelle.

Audemars Piguet solidifies its reputation

By the early 1900s, Audemars Piguet had increased its collaborative efforts, working with famous jewelry and watch retailers abroad. From Bulgari in Rome and Cartier in Paris, to Tiffany & Co. in New York, Audemars Piguet produced watches for the luxury maisons of the western world. The dials of these timepieces bore either solely the retailer’s name or a double branding. The quality they exuded helped further cement Audemars Piguet’s reputation within the affluent circles of high society. This reputation among the wealthy would serve them well in times of economic hardship. Thanks to these loyal, wealthy clients, to this day, the brand has never completely ceased production of its mechanical marvels.

In the hands of the next generation

Between 1918 and 1919, both Jules Audemars and Edward Piguet passed away. The pair left the company to their sons, Paul Louis Audemars and Paul Edward Piguet. Both men were well-trained watchmakers, prepared to carry on the legacy of their forebears. The second-generation leaders of Audemars Piguet continued to innovate with more world firsts. Indeed, 1921 saw not one, not two, but three of these. First, as thin was “in,” Audemars Piguet pioneered the slimmest pocket watch movement at the time, caliber 17SVF#5, at only 1.32mm in thickness. Soon after, Audemars Piguet introduced the world’s smallest repeater movement at 15.8mm in diameter. Cased in a platinum pendant, the entire watch was just 21.1mm in diameter and was produced especially for the then president of Tiffany & Co.

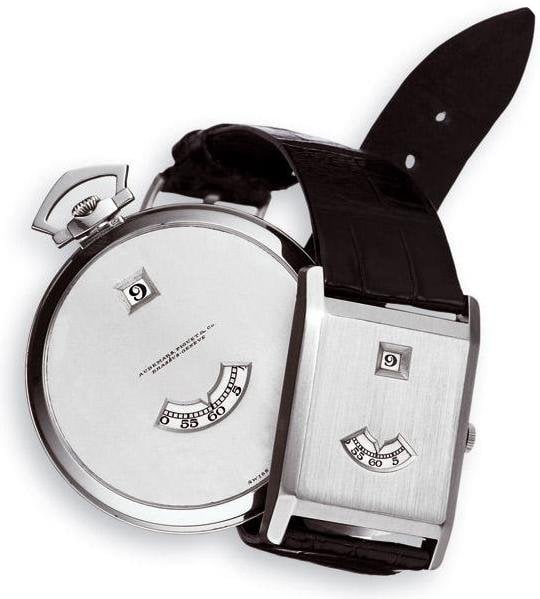

To cap off 1921’s achievements, AP also released the world’s first jump hour wristwatch. Launched alongside a pocket watch counterpart, both timepieces employed the caliber HPVM10. They featured mostly solid case fronts, apertures for jumping hours, and scrolling minute discs. Within just a few years, the brand was also producing wristwatches with more traditional dials, minute hands, and jump hour indicators at 12 o’clock.

While other famous makers such as Patek Philippe, Rolex, and Cartier followed suit in that decade, by the 1930s, many brands on the more “pedestrian” end of the market had also adopted the jump hour display. This showed that Audemars Piguet had been a true stylistic visionary ahead of its time. Along with jump hour watches, the manufacture also focused on minute repeater wristwatches. Audemars Piguet repurposed many movements from its ladies’ pendant repeaters into men’s wristwatch cases during this time.

Dark times

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and Great Depression, however, meant the beginning of extremely tough times for the manufacture. Having lost some of its most important clients in the US, sales around the world also plummeted. With such little demand for luxury goods, in 1929, Audemars Piguet was nearly forced to close its doors. The company laid off almost all of its employees, with only three watchmakers remaining and building only one watch. Unfortunately, the history of the brand during this time is not extremely well-documented. It is said that throughout the Great Depression, Audemars Piguet produced just three watches in total. Cameron Weiss, a former watchmaker at Audemars Piguet, has gone on record stating that the brand has produced at least one grand complication watch every year since its debut. Perhaps it was this most honorable horological pursuit that kept the brand alive in its darkest days.

Audemars Piguet is widely credited with creating the first skeletonized wristwatch in 1934. Unfortunately, I am unable to find photographic evidence of that particular piece. Nevertheless, the brand definitely pioneered skeletonization in its wristwatches throughout the following decades. At the time, wristwatches were truly taking over. The wearer now had far fewer chances to appreciate the craftsmanship of the movement than he or she may have with an easily opened pocket watch. While many pocket watches had either hinged or easily removable case backs, most wristwatches simply did not. It was not until 1982 that Chronoswiss would release the first wristwatch with a front dial and display case back. Thus, a skeletonized wristwatch would be a fitting reminder to the wearer of the artistry within Audemars Piguet’s mechanical masterpieces. To this very day, the skeletonization technique remains a specialty of the brand.

Audemars Piguet’s thinnest movement for a pocket watch, caliber 17SVF#5. Image credit: www.PuristSPro.com

Ultra-thin innovations

After 1935, the markets began to stabilize, and Audemars Piguet’s production picked up steam once again. During this time, customers began to value the elegance of thin, svelte timepieces. As you may recall, AP had already begun making its mark on the world of ultra-thin watches back in the early ‘20s with its 1.32mm-thick pocket watch caliber. The size of a pocket watch, however, was really only limited by the size of one’s pocket. With more horizontal space to spread out components, it was no longer too challenging to make slim pocket watch movements. By the late ‘30s, however, wristwatches were not going anywhere. As such, the battle for who could most masterfully miniaturize movements had begun.

In 1938, Audemars Piguet released its 9ML caliber. At just 1.64mm thick, the movement was the thinnest wristwatch caliber at the time. The brand placed the movement both in wristwatches and gold coin watches. The 9ML caliber would also serve as a base for collaboration with Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin over the coming decades.

Chronographs in times of crisis

In 1939, war struck again, and the brand faced the second worldwide calamity in a decade. But while sales dropped, Audemars Piguet thankfully did not suffer as badly as it had during the Great Depression. On the contrary, it was actually quite a productive time for the brand. During these years, Audemars Piguet focused on producing more chronograph wristwatches.

As Patek Philippe and others would also do, AP utilized a variety of 13-ligne, VZ series base calibers from Valjoux to power these chronographs. While modern Valjoux movements have become ubiquitous, VZ calibers are still known as some of the finest chronographs of the era. Available with both mono- and dual pushers, in double- or triple-register layouts, and with and without complications, the calibers were modified to AP’s standards. The brand housed them mostly in gold cases with a few two-tone gold/steel exceptions. While Audemars Piguet produced only 286 chronographs in total throughout the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, the brand actually produced a whopping 210 of them in the six-year span of World War II from 1939 to 1945.

Another area of development in AP’s production in the ‘40s was high-precision watches. These timepieces also used the same base Valjoux chronograph calibers, but with the chronograph functions removed. This allowed further modification for increased accuracy. Removing the chronograph functions resulted in much less friction among the components, and therefore, more power. The additional energy, the calibers’ strong mainsprings, and the ¾ plate architecture meant that the timepieces could be not only thin and elegant but also sturdy and highly precise. Many of these models even used repurposed dual-register chronograph dials. Running seconds remained at nine- o’clock, and a “Precision” designation graced the sub-dial at three o’clock. Other variants even had an early “world time” display. More of a reference than a true complication, world cities’ relative time differences to the wearer’s time zone were simply printed within the sub-dial.

In 1953, Audemars Piguet released the ultra-thin, manually wound caliber 2003. Produced in a collaborative effort with Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin, the new caliber was based on Audemars Piguet’s previous record-setting slim caliber 9ML from 1938. The new caliber 2003 retained the 9ML’s 1.32mm thinness. A reduction in the number of bridges, however, made this new movement more robust. Having provided the 9ML base, Audemars Piguet was able to get a two-year head start on the movement’s production. In 1955, Vacheron Constantin was at last able to put utilize it, giving it the moniker 1003. Jaeger-LeCoultre, dubbing it the 803, curiously never actually used the caliber in its own timepieces. The new ultra-thin movement proved reliable, and under Audemars Piguet, it remained in production for 50 years. This beneficial collaboration would pave the way for further ventures in the following decade.

Revolutionizing the perpetual calendar

The next pioneering moment in the manufacture’s history, however, came in 1955. That year, Audemars Piguet released the world’s first perpetual calendar wristwatch with a leap year indicator. It cannot be overstated how important an evolution this was. Thirty years prior, Patek Philippe had released the reference 97975, the first perpetual calendar wristwatch. A leap year indicator, however, had not appeared on that watch, nor any other perpetual calendar since. Thus, for the calendar and to be set correctly, either for the first time or after an unknown interval of disuse, the watch needed to be adjusted by a watchmaker. This all changed, however, with the release of Audemars Piguet’s reference 5516. At long last, the user himself could set the calendar on his watch, without worrying if it would handle the quadrennial 29th of February properly or not.

The brand produced three examples of the first 5516 reference in 36.5mm yellow gold cases, utilizing the caliber 13VZSSQP. If the “VZ” sounds familiar, it’s because this caliber, as its chronograph and high-precision brethren before it, was built using a (heavily) modified Valjoux 13-ligne base movement.

The 5516’s first iteration featured a pointer date, moonphase at 12:00, day at 9:00, annual month at 3:00, and 48-month and leap year indicator at 6:00. While this layout was effective, the bottom sub-dial was rather text-heavy. In the second iteration of the 5516, Audemars Piguet switched the positions of the moonphase and leap year indicators, doing away with 48-month indications completely. This design was cleaner and much more legible, and it further highlighted the leap year indicator the brand had pioneered. It would take Patek Philippe 20 more years to include a leap year indicator on a perpetual calendar.

In the 1960s, Audemars Piguet began experimenting, to some degree, with the design of its cases. While many pieces from the decade remained quite traditional in their design, others were more flamboyant. Many were characterized by wide bezels (with or without texture) and more adventurous shapes than previously seen from the brand. However, exceptional elegance nevertheless remained the focus of the brand’s offerings.

Thus, when Jaeger-LeCoultre, seeking to develop the world’s thinnest centrally-wound automatic movement, approached Audemars Piguet for collaboration, the brand was happy to aid in the continued quest for elegance. Partnering also with Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe, the group produced the world’s thinnest automatic caliber with a central rotor. The result was a movement that all the contributors would share. Audemars Piguet named it caliber 2120.

The future calls: 2120 in 1967

At just 1.12mm thicker than the brand’s ultra-thin manual caliber 2003, the new 2120 movement came in at just 2.45mm thick. The caliber’s full rotor was remarkably engineered. With much of its mass concentrated along its outermost edge, the majority of the rotor remained extremely slim. While this weight distribution strategy could have caused imbalance and inefficient winding, the designers preemptively counteracted this through the use of ruby roller supports on the underside of the rotor. These rollers ran along a metal enclosure that surrounded the rest of the caliber’s moving components. This allowed the edge of the rotor to be in the closest possible contact with the mainplate itself. The time-only 2120 caliber then saw the addition of a date wheel in its 2121 variant. This added a mere 0.6mm in thickness, for a total of 3.05mm.

In addition to automatic winding, the 2120 and 2121 further improved upon AP’s previous ultra-thin calibers in two important ways. First, the addition of Patek Philippe’s free-sprung Gyromax balance offered the opportunity for a more precise rate adjustment. In addition, a new shock protection system ensured a level of robustness not previously seen in the brand’s earlier ultra-thin movements. The caliber was not only slim and elegant but also better equipped to withstand the rigors of a more active, sporty lifestyle. As fate would have it, a caliber such as this would prove to be exactly what the doctor ordered. Just five years after its 1967 release, Audemars Piguet would choose the 2121 to power the brand’s most industry-shaking icon.

And that, dear Fratelli, is where I leave you: on the cusp of a revolution in watchmaking that would both redefine the entire industry and ensure the survival of our beloved mechanical marvels against all odds. We hope you have enjoyed Part One of this history of Audemars Piguet. We will see you back here in two weeks for Part Two of the brand’s incredible story.