Celebrating 60 Years Of The Omega Speedmaster Becoming NASA Flight Qualified

As I landed in Zurich last Monday, I wondered what flying must have been like 60 years ago. Besides the cigarette smoke, one of the most significant differences would’ve been the vital role that analog tools played in guiding the plane to its destination and doing so safely and on time. Today, it feels as trivial as jumping on a train. But six decades ago, long before the digital era we live in today, it must have been a vastly different experience. The plane glided smoothly onto the Swiss tarmac in Zurich at exactly 13:32:55 local time after spending precisely one hour, 22 minutes, and 40 seconds in the air. I knew all this thanks to my trusty Speedmaster. Back in the ’60s, that would have been the only method of obtaining that information.

I then began to wonder what it was like to fly into space 60 years ago. Today, we see images of the celebs du jour taking Bezos’s rocket into the upper atmosphere. It’s not quite space, but the fact that this is just a joyride for the rich and famous says a lot about how far we’ve come. In the early ’60s, it was exclusively for the brave few — the Armstrongs, Aldrins, and Cernans of this world. Alongside the right personnel, every piece of equipment played a vital role in getting astronauts to space and safely back home again. One such piece of equipment, meticulously selected by NASA, was the Omega Speedmaster. In 1965, just four years before its lunar debut, it received official NASA Flight Qualified status. This has been engraved onto the back of just about every Moonwatch made since. But how exactly did this come to pass?

A watch for Astronauts

On Monday, September 21st, 1964, Flight Crew Operations Director Deke Slayton issued an internal memo stating that the Gemini and Apollo flight crews needed a highly durable and accurate chronograph. This request came from astronauts who approached Slayton, saying they needed a watch they could use during training and flight. This memo landed on the desk of NASA engineer James Ragan, who then put together a request for quotation and sent it to about 10 watch manufacturers, including Omega, Rolex, Longines, Hamilton, and Lucien Piccard.

Of the 10, only four responded — Rolex, Longines-Wittnauer, Hamilton, and Omega. NASA immediately disqualified Hamilton because the company sent a pocket watch instead of a chronograph wristwatch. Perhaps something in the brief was lost in translation. Still, it was not the brand’s proudest moment. Longines-Wittnauer sent a reference 235T chronograph, Rolex US sent its reference 6238 chronograph, and Omega US sent the Speedmaster 105.003. The Rolex 6238 and Longines-Wittnauer 235T each used a Valjoux 72 movement, while the Speedmaster relied on the Lemania-based caliber 321.

Test requirements

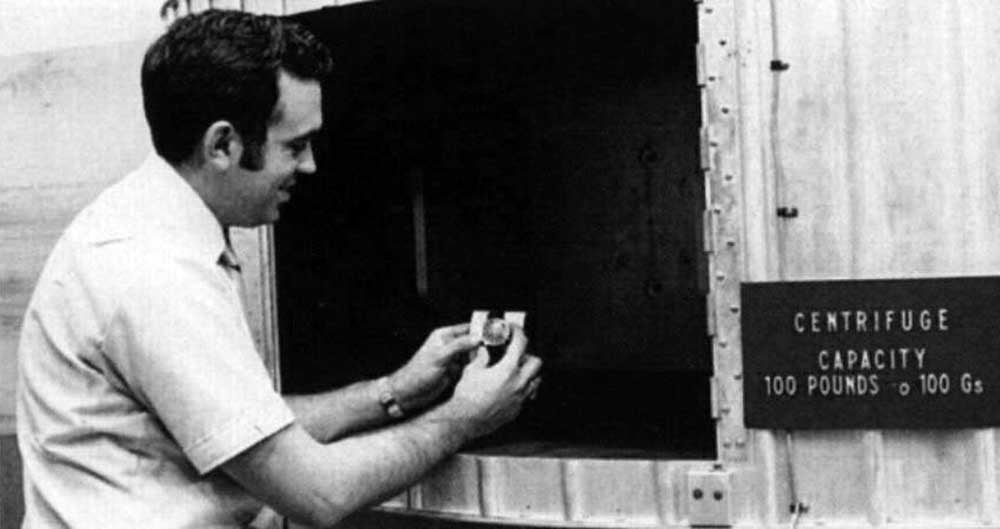

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) engineers developed a series of tests to evaluate these watches and ensure their suitability for astronauts’ in-flight use. They were as follows:

- High-temperature test: 70 °C for 48 hours and then 93 °C for 30 minutes in a partial vacuum.

- Low-temperature test: -18 °C for four hours.

- Vacuum test: heated in a vacuum chamber and cooled to -18 °C for several cycles.

- Humidity test: ten 24-hour cycles in >95% humidity with temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 70 °C.

- Corrosion test: an atmosphere of oxygen at 70 °C for 48 hours.

- Shock-resistance test: six shocks at 40 g in six different directions.

- Acceleration test: progressive acceleration to 7.25 g for about five minutes and then to 16 g for 30 seconds on three axes.

- Low-pressure test: pressure of 10.6 atmospheres at 70 °C for 90 minutes and then at 93 °C for 30 minutes.

- High-pressure test: air pressure of 1.6 atmospheres for 60 minutes.

- Vibration test: random vibrations on three axes between five and 2,000 Hz with an acceleration of 8.8 g.

- Sound test: 130 decibels at frequencies from 40 to 10,000 Hz for 30 minutes.

Earning NASA Flight Qualification

NASA’s standards allowed each watch a maximum average deviation of six seconds per day during normal use after testing. According to official documentation we’ve seen from Omega’s archives, the Rolex 6238 failed the humidity test, with the movement simply having come to a stop. In addition, the watch failed the high-temperature test. The Longines-Wittnauer 235T also failed the high-temperature test because the crystal warped and compromised its seal with the case.

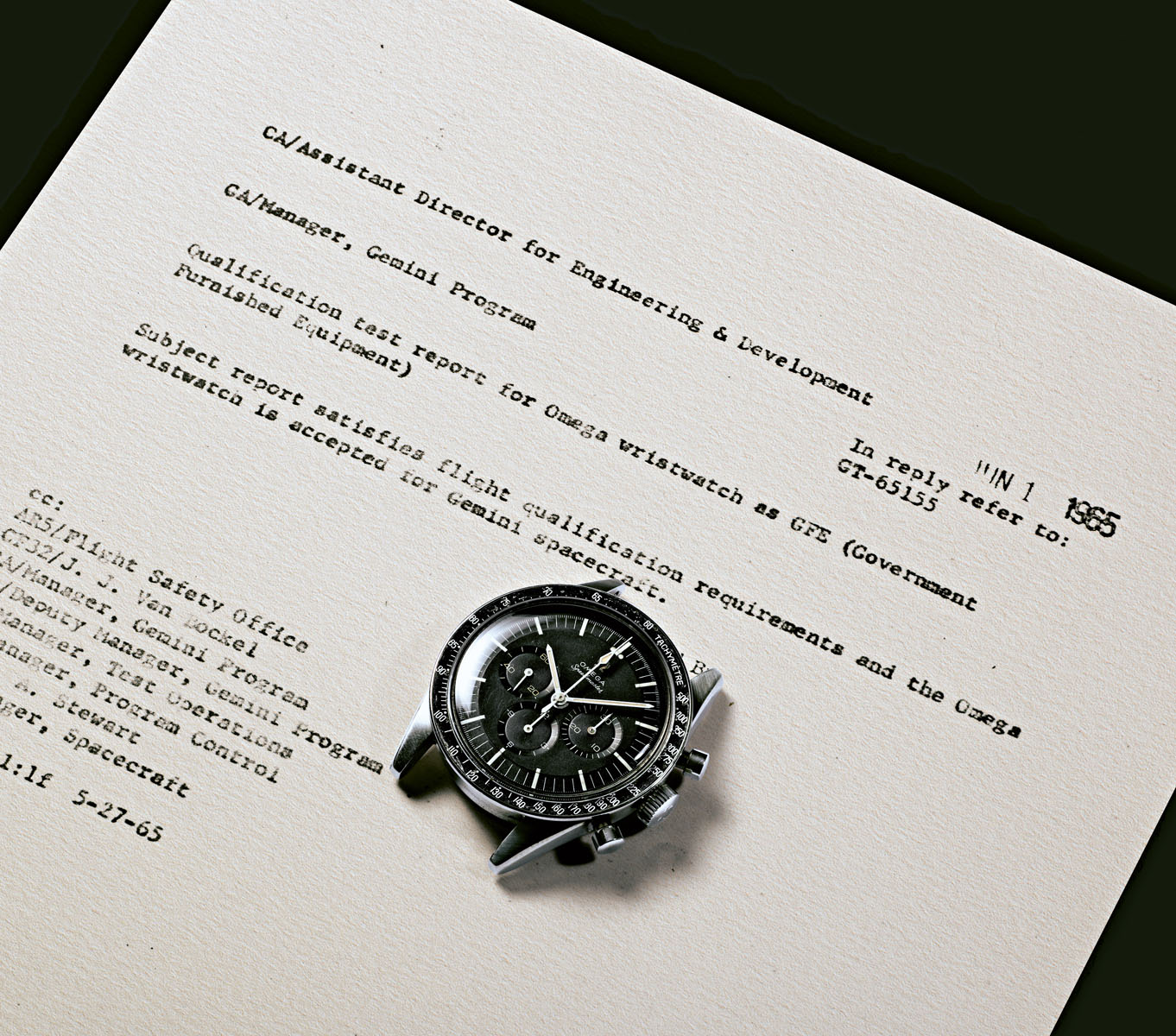

NASA completed all these tests on March 1st, 1965. Funnily enough, on March 23rd, 1965, the Speedmaster 105.003 went into space on the wrists of astronauts Virgil Grissom and John Young. Only a few months later, on June 1st, the Omega Speedmaster 105.003 received its qualification (not certification — NASA doesn’t certify anything) to become the chronograph used for all manned space missions. Two days later, on June 3rd, NASA astronaut Ed White wore not one but two Speedmaster 105.003 watches over his space suit during the first spacewalk performed by an American. If you want to read the full story on how the Speedmaster became the Moonwatch, you can find RJ’s full write-up here.

Celebrating 60 years of the Omega Speedmaster becoming NASA Flight Qualified

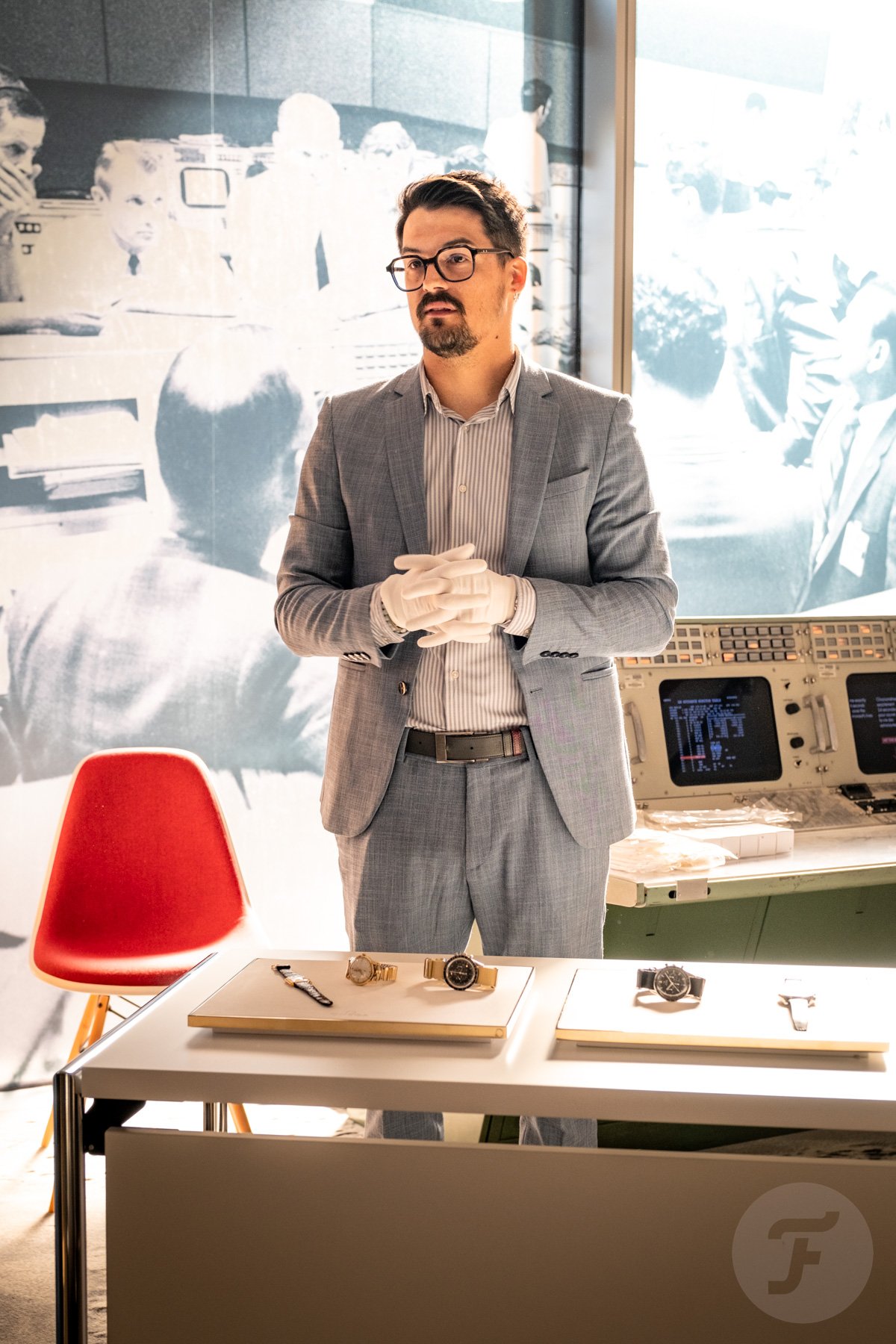

Omega hosted a visit to its museum in Biel to mark the occasion, giving us unique access to a handful of very special watches. These museum pieces had close ties to Omega’s involvement in the Space Race and the brand’s collaboration with NASA.

Loïc Voumard, Omega’s head of brand heritage, accompanied us into the museum before taking his place. This was behind a table covered in truly incredible watches and in front of one of the original NASA desks once used at mission control in Houston. After providing a brief introduction to each watch, Loïc passed us some pairs of white gloves and encouraged to get up close and personal with all of them.

I had the unique opportunity to see, hold, and photograph these watches, and I wanted to share the experience with you today. So, let’s take a closer look at five of them (of which only three are Speedmasters). We’ll discover who they belonged to and the role each played in the story that led to putting man on the Moon and to the Speedmaster becoming qualified for all space flight.

John F. Kennedy’s Omega Slimline OT3980

We begin with a watch that belonged to former President John F. Kennedy. Grant Stockdale (a supporter, friend, and later US ambassador to Ireland) gifted it to him in 1960, when Kennedy was still a senator. The back boldly predicted Kennedy becoming the 35th president of the United States with an engraving. Fittingly, the watch was on Kennedy’s wrist during his inauguration on January 20th, 1961. Four months later (on May 25, 1961), addressing Congress, President Kennedy declared: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

He echoed this sentiment in front of 40,000 people during his famous “We choose to go to the Moon” speech, which he delivered on September 12th, 1962, at Rice University in Houston, Texas. This was not exactly met with the enthusiasm we might imagine today. Regardless of the challenge, Kennedy supported NASA, committing to provide them with the resources necessary to achieve this goal. The rest, as you know, is history. Omega created a faithful reissue of this watch in 2005 in a limited run of 261 pieces.

Gordon Cooper’s Omega Seamaster

Before we get to the Speedmasters, I thought I’d highlight something that looked somewhat out of place on the table at first glance. This dressy 34mm Seamaster chronometer belonged to one Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr. After serving in the US Air Force as a fighter pilot, he graduated to test pilot in 1956 and officially became an astronaut in 1959. Among the many accolades to his name, Cooper was the first American to spend an entire day in space, the last American launched on a solo orbital mission, and the first astronaut to make a second orbital flight. Cooper achieved that last feat during the Gemini 5 mission, in which he and Pete Conrad set a new space endurance record by traveling 3,312,993 miles (5,331,745 km) in 190 hours and 56 minutes.

This nearly eight-day mission proved that astronauts could survive in space long enough to get to the Moon and back. This piece exemplifies the kind of watch that astronauts would wear when not working. Ultimately, Speedmasters were used as tools and only later worn outside missions. It co-existed alongside a Bulova Accutron and an Omega Speedmaster CK2998. Speaking of which…

Walter “Wally” Schirra’s Speedmaster CK2998-4

With that, we arrive at the first Speedmaster. And how fitting that it should be not just a CK2998-4, a reference known as the “first Omega in space,” but also the actual first Omega in space. Astronaut Wally Schirra — one of the original seven astronauts, the first to go to space three times, and the only astronaut to have flown into space in the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs — owned and wore this very watch on the Mercury Sigma 7 mission in 1962, three years before NASA officially qualified the Speedmaster for space flight.

This nine-hour flight was the longest US crewed orbital flight achieved at that point in the Space Race. Its focus was mainly on technical aspects of the Mercury spacecraft, which confirmed its durability ahead of the longer, one-day Mercury-Atlas 9 mission in 1963. Interestingly, the second Omega in space would be Gordon Cooper’s aforementioned CK2998-4.

The gold Speedmaster intended for Richard M. Nixon

On the table in front of Loïc were four gold Speedmasters, including those that once belonged to astronauts Gordon Cooper, Wally Schirra, and Thomas Kenneth Mattingly. However, one that caught my interest was one not engraved with an astronaut’s name but, rather, the name of former President Richard M. Nixon. Politics aside, two facts make this golden Speedmaster particularly interesting. The first is that the watch never officially belonged to Nixon. He had to decline it since it would not have been legal to accept a gift of such high value from a foreign company. Former Vice President Spiro Agnew also declined his gifted gold Speedmaster.

The second fact is that Nixon’s was the very first of these gold Speedmasters made. These watches were all numbered, and the one intended for the former president was watch number one (number two being the one made for the former vice president). If you want to read about these commemorative Speedmasters and their presentation, you can find more information in RJ’s articles here and here.

Gene Cernan’s Moon-worn Speedmaster 105.003

We finish things off with a truly remarkable watch. To stand out in a crowd made up of some of the watches we’ve just seen takes something truly special. Gene Cernan’s Speedmaster 105.003 is just that. Not only was this watch worn in space on the wrist of an astronaut, but it’s also one of the few known Speedmasters to have been worn on the Moon. This specific watch holds the title of the last Speedmaster (and last watch, for that matter) worn on the Moon. And, as you can see, Cernan wore this watch well. The case is scratched, the bezel is gone, and the crystal is cracked. It’s plain as day that it was used as a tool, not a toy.

When asked to theorize about the bezel’s absence, Loïc explained that some astronauts were not fans of the tachymeter and its earthly ambitions. Some did away with it in favor of 60-minute scales. Why Cernan’s bezel is missing remains a mystery. Another interesting fact explained the use of the distinctive JB Champion bracelet. Supposedly, its main feature was its versatility in terms of size. It could fit on the wrist and over the sleeve of a flight suit. Astronauts also liked that these bracelets would easily break when snagged, due to their delicate construction. This gives insight into the pragmatic nature necessary to achieve the many impressive feats mentioned alongside these watches today; it’s better to lose a watch than a hand.

Final thoughts

If you ever find yourself in Biel, I highly recommend visiting the Omega Museum. What we looked at today is just a fraction of what you’ll find on display there. For more information, check out the Cité du Temps website.