A Brief History Of Time: Rolex’s Complete Brand History — Part One: 1905-1945

Rolex is a name that has truly transcended the watch industry itself. Though it is neither the oldest nor the most prestigious watch manufacture in the world, Rolex is undoubtedly the most well-renowned. In fact, it’s nearly impossible to find an adult on this earth who has not heard the name. Due to this legendary reputation, Rolex watches of both the past and the present almost serve as their own global currency. But it wasn’t always this way.

While Rolex has always strived for excellence, the brand didn’t set out to make the most expensive, prestigious timepieces in the world. Rather, since its founding over 120 years ago, the brand had one ultimate goal: to make the most functional, reliable timepieces possible. Throughout its history, Rolex’s innovations have served as a means to that end. Today, we’ll explore how the brand got started. We’ll discover all of the most important developments in its early history. Most importantly, we’ll see how these early innovations laid the foundation for the brand’s present-day status. So join me today, on a journey through time, as we discover the early history of Rolex.

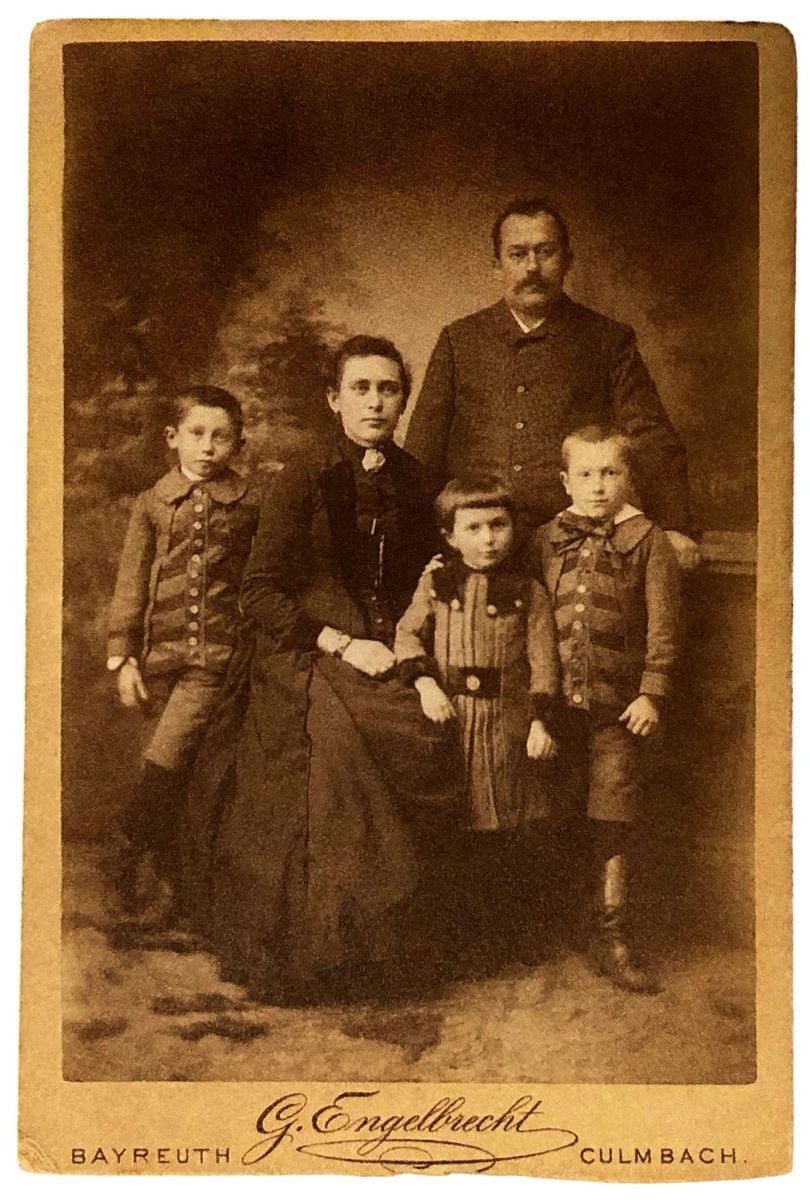

The Wilsdorf family in 1887. Rolex-founder Hans Wilsdorf (front right) was the second of three children.

The early life of Hans Wilsdorf

On March 22, 1881, the future founder of Rolex, Hans Wilsdorf, was born in Kulmbach, Bavaria, Germany. He was the middle child of a successful family. Wilsdorf’s mother descended from the renowned Bavarian Maisel brewing family, and his father owned a successful hardware store. Unfortunately, when Wilsdorf was 12 years old, his mother passed away. Just months later, his father did as well. Wilsdorf’s maternal uncles assumed custody of the boy and his siblings. They sold his father’s hardware business for a considerable sum, placing the money in a trust fund until the children reached adulthood. Wilsdorf’s uncles supported him with an excellent education. They also instilled in him a strong work ethic, an appreciation for self-reliance, and pride in caring for one’s possessions. As an adult, Wilsdorf would credit these values as the keys to his success.

Until the age of 18, Wilsdorf attended boarding school in Coburg, Germany. He was proficient in mathematics and foreign languages, especially French and English. After graduating, he moved to Geneva to work for a pearl distributor. At this job, Wilsdorf learned much about business, trade, and technology. In 1900, his foreign language skills took him to La Chaux-de-Fonds. There, the 20-year-old took up an English correspondent position at Cuno Korten, an exporter of Swiss pocket watches. As part of his duties, Wilsdorf wound hundreds of watches per day and checked them for accuracy. This led him to develop an intense fascination with horological precision.

The birth of Wilsdorf’s vision

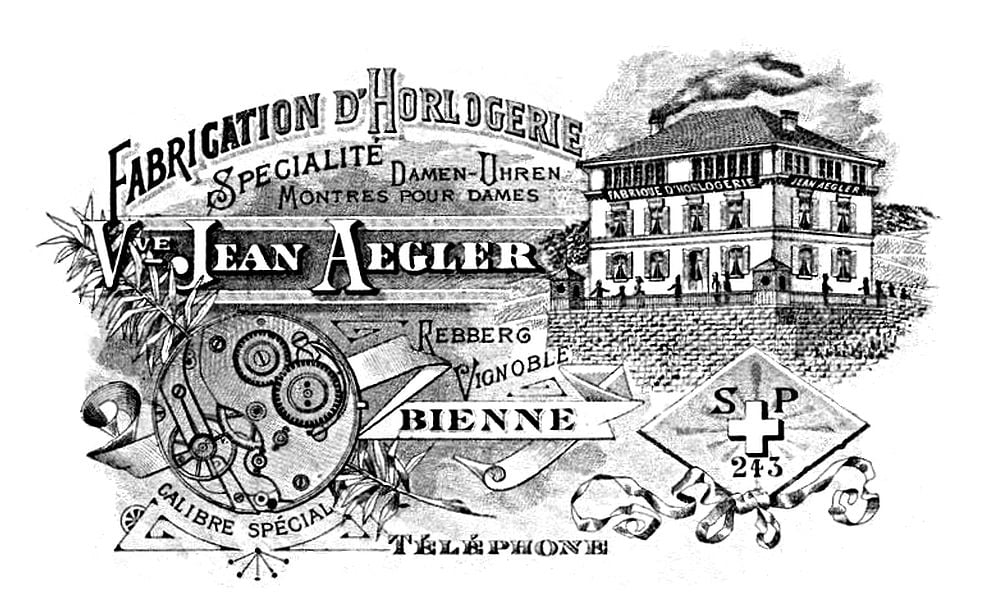

By working with English-speaking clients, Wilsdorf gained extremely valuable skills in international marketing. He lived in La Chaux-de-Fonds until 1902 when the German government called him home to enlist in the army. Before leaving Switzerland, however, Wilsdorf discovered the Aegler movement manufacture in Bienne. The maker’s compact lever-escapement movements intrigued him. In the age of pocket watches, Aegler’s “wristlet” calibers stood out not only for their innovative construction but also for their competitive prices. Though watches, in general, fascinated him, Wilsdorf wasn’t particularly fond of digging one out of his pocket just to check the time. At the time, however, the public saw wristlets strictly as delicate, women’s jewelry. Critics believed such timepieces would never be able to withstand the rigors of daily life. Convinced otherwise, Wilsdorf dreamed of placing Aegler’s calibers in robust, convenient wristwatches, the likes of which the world had never seen.

Upon leaving the army in 1903, 22-year-old Wilsdorf took his family inheritance and moved to London. On his journey there, however, German thieves robbed him, taking the entire sum (33,000 German gold marks). Escaping with his life, Wilsdorf forged on to Britain and secured a job at a watchmaking firm. There he learned how competent his employers were in marketing. Interestingly, though, he also learned that they lacked any technical specialization. He used this insight to further develop his vision for his own highly specialized wristwatch company. Wilsdorf then met his future wife, Florence Frances May Crotty, and attained British citizenship. He also met Alfred Davis, an older businessman who was very intrigued by Wilsdorf’s dream. With Davis agreeing to provide half of the initial investment, Wilsdorf borrowed the other half from his siblings, and the duo started their own watch company, Wilsdorf & Davis, in 1905.

Wilsdorf & Davis’s first watches

Alfred Davis married Wilsdorf’s younger sister, strengthening the business partnership between the two. The duo set up shop in Hatton Garden in London and went to work selling specialized watches and watch parts. Though the new company’s first watch was a leather-backed “portfolio” pocket watch for travelers, Wilsdorf maintained his enthusiasm for the “wristlet”. He strongly believed that he could transform the public’s perception, making the wristlet into a popular timepiece. In 1905, Wilsdorf traveled to Bienne to visit Aegler, whose movements still fascinated him. There, he placed the largest-ever order for wristlet movements, totaling several hundred thousand Swiss francs. This first business deal would lead to Aegler becoming Rolex’s primary movement supplier for the next 100 years.

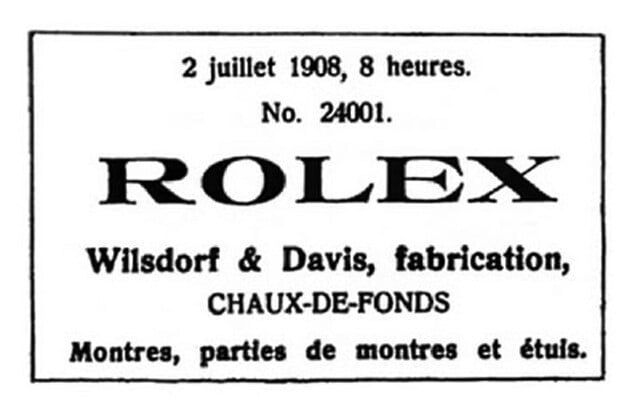

Wilsdorf made trips to Bienne several times a year. He worked closely with founder Jean Aegler’s son Hermann to produce exclusive movements in a variety of sizes for both men’s and women’s watches. Wilsdorf & Davis released silver and gold-cased watches on leather straps, followed shortly thereafter by models on gold bracelets. In just three short years, the company had achieved remarkable success in the British market. Wilsdorf then sought to create a short, punchy brand label that would elevate its offerings to household-name status. After combining the letters of the alphabet in hundreds of ways, Wilsdorf remained unsatisfied. Until one day, however, when on a horse-drawn double-decker ride through London, Wilsdorf later recalled, “a good genie whispered in my ear: ‘Rolex.'” The name was perfect. It was easy to inscribe on a dial or movement, easier to pronounce in any language, and easiest of all to remember.

Rolex was born

Wilsdorf registered the name just days later, on July 2nd, 1908. Due to British watchmaking conventions at the time, however, it would take nearly 20 years before all of the brand’s watches would feature the Rolex name on the dial. Instead, many featured the names of the retailers where they would be sold. Nevertheless, Wilsdorf set about developing his wristwatches’ worldwide reputation in earnest. In a world still quite skeptical of wristwatches, the first step was to prove their accuracy. In 1910, Rolex submitted its first wristwatch movement for accuracy testing to the Official Bureau of Watch Observation in Bienne. The movement passed 15 days of tests with flying colors. It became the first wristwatch movement ever to gain Swiss chronometer certification.

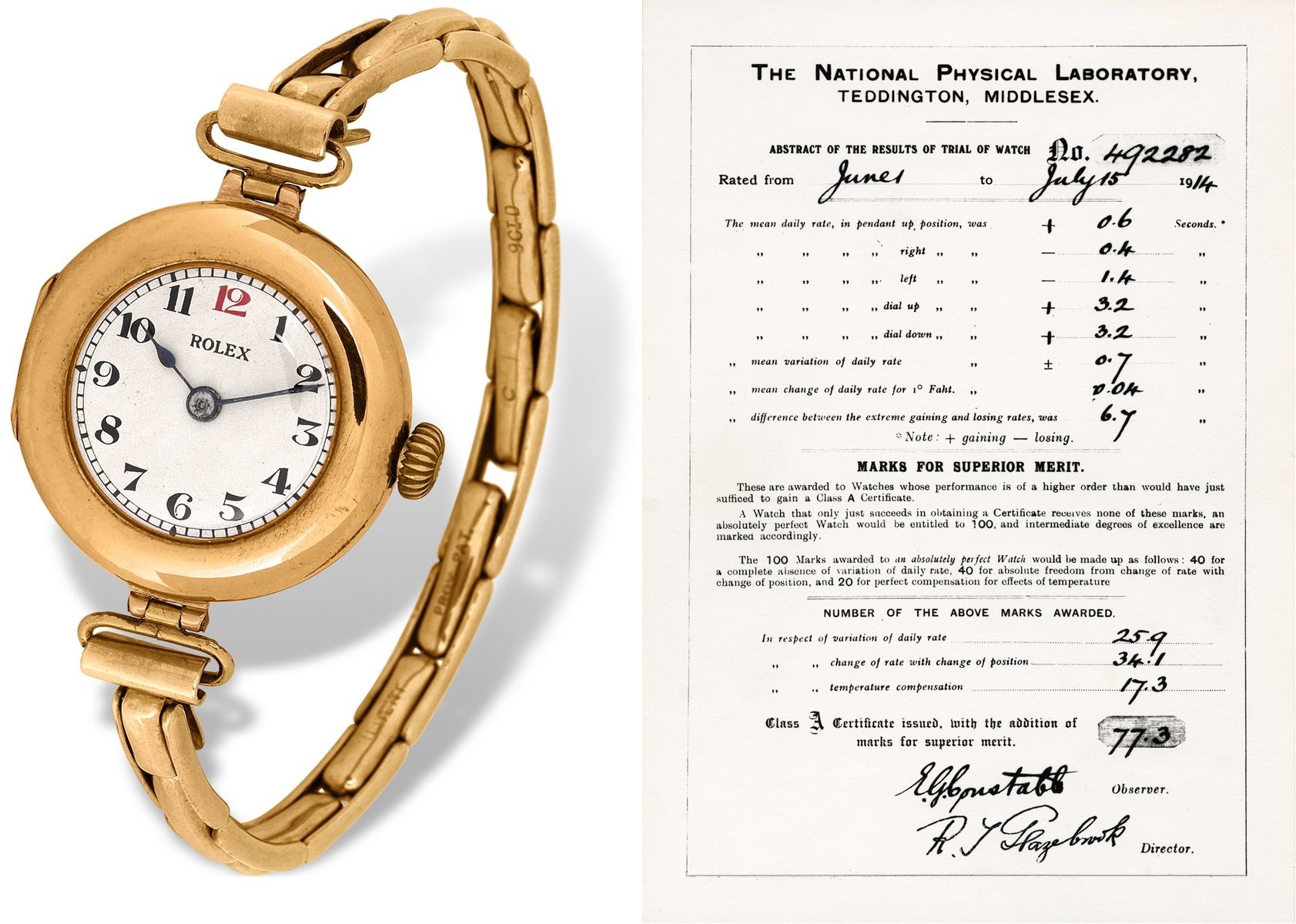

The first Rolex watch to receive chronometer certification from the Kew Observatory and its timing certificate

In 1914, seeking to further its reputation for accuracy, Rolex submitted a 25mm women’s wristwatch to the Kew Observatory in England. The observatory’s standards were the highest in the world at the time. Its Class A certificate was a coveted chronometric prize, requiring 45 days of tests in five positions and at three different temperatures (average, extreme cold, and extreme heat). In the end, the tiny wristlet passed the stringent tests with a mean variation of ±0.7 seconds per day. The Kew Observatory awarded the watch with the Class A certificate and 77.3 of 100 total additional points for excellence. Up until that point, it was a feat only marine chronometers had achieved.

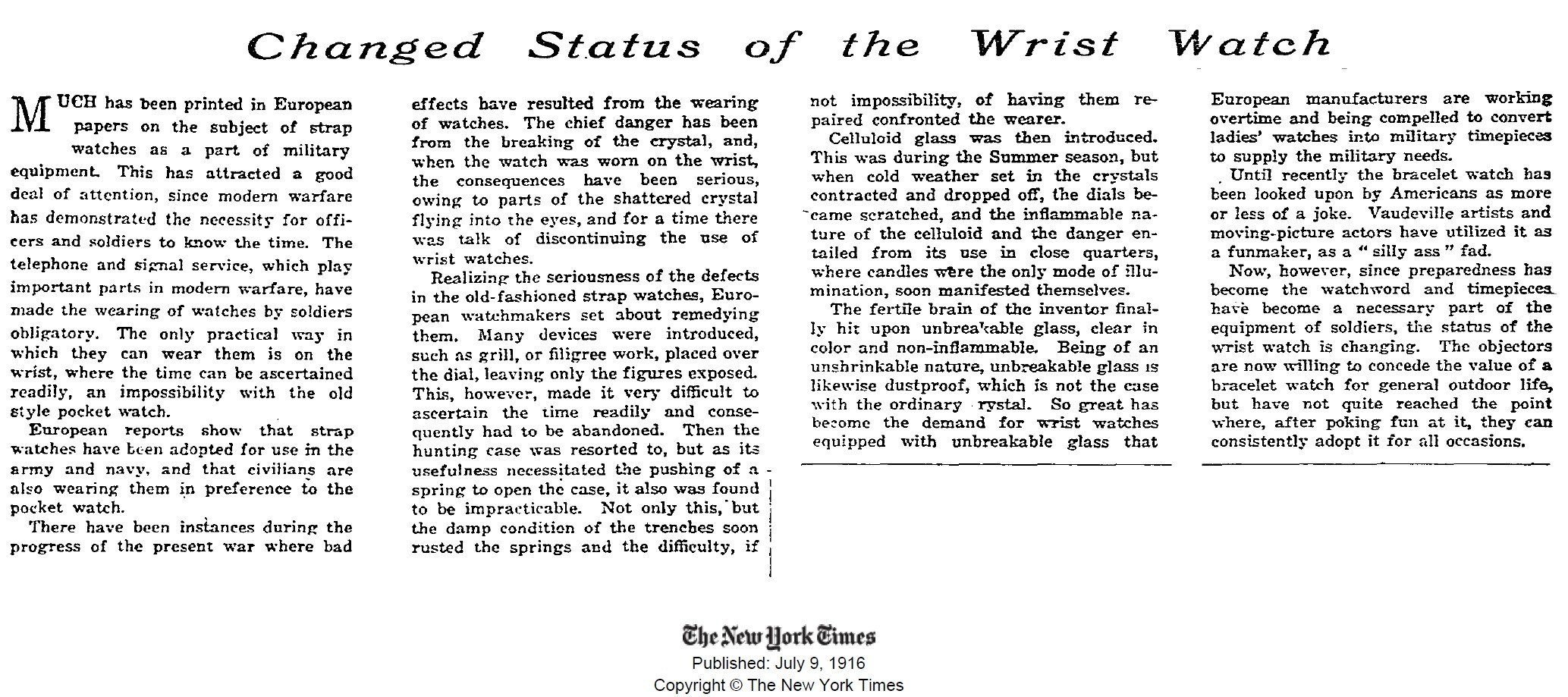

World War I brings about change

Less than two weeks after Rolex obtained its Class A chronometer certificate, World War I officially began. Due to growing anti-German sentiment, Wilsdorf & Davis officially changed its name to The Rolex Watch Co. Ltd. in 1915. The same year, the British government placed a 33.3% tax on imported goods. This affected Rolex greatly, and the duo decided to relocate the company’s headquarters from London to its offices Bienne. This not only allowed Rolex to avoid import tax but also to be closer to the Aegler factory, which had changed its official name to Aegler SA, Rolex Watch Co. in 1914.

During the war and in the years that followed, public perception of the wristwatch changed dramatically. Soldiers had realized how convenient it was to time strategic military operations at a simple turn of the wrist. Indeed, it was far less time-consuming than laying down a gun, removing gloves, unbuttoning multiple layers of clothing, reaching into a vest pocket, taking out a pocket watch, checking the time as quickly as possible, then repeating the process in reverse. Consequently, many soldiers had their pocket watches modified with soldered wire lugs and leather straps. Even after returning home, many soldiers continued to wear their watches on their wrists. Slowly but surely, wristwatches became a masculine symbol of gallantry. It was evident that Wilsdorf had been right all along.

In 1919, Rolex purchased an ownership stake in the Aegler factory. Although the two companies continued to operate independently, in Wilsdorf’s eyes, the purchase brought Aegler into the Rolex family. The same year, Wilsdorf purchased Alfred Davis’s share of Rolex, becoming sole proprietor. He once again relocated Rolex headquarters, this time to the “City of Watchmaking,” Geneva.

The next frontier for wristwatches

From 1919 onward, the Rolex/Aegler factory in Bienne would focus on the production of movements. The company’s Geneva base would serve as the site of production for watch cases, bracelets, movement inspection, final assembly, and distribution and export. In 1920, Wilsdorf changed the company’s official name one final time to Rolex SA. The brand maintains this official designation, as well as its Geneva headquarters, to this day.

Wilsdorf’s vision of wristwatch popularity was finally coming to fruition. He knew that Rolex must devote its efforts to producing the strongest, most reliable wristwatches on the market. This would require not only certifying all of the brand’s movements as chronometers but also housing them in cases that were impervious to the elements. Wilsdorf recalled telling his staff time and time again, “we must succeed in making a watch case so tight that our movements will be permanently guaranteed against damage caused by dust, perspiration, water, heat, and cold. Only then will the perfect accuracy of the Rolex watch be secured.”

Rolex set about designing a “waterproof” watch case. Its early designs featured a hermetic seal. Their coin-edged, screw-down caps functioned like the lid of a jar, sealing an inner case inside an outer one. This design was not ideal, however, as it also sealed the winding crown inside. Thus the wearer would need to unscrew the cap every single day simply to wind the watch. As one might imagine, this design did not survive long.

The Oyster case makes a splash

Rolex engineers slaved away to improve the design. They developed a case that featured both a screw-down back and a screw-down coin-edged bezel, similar to the cap on the previous version. Rather than sealing another case inside, however, the bezel and back screwed into a case middle hewn from a single piece of gold. The final touch would be a screw-down crown to ensure the utmost water resistance. This element, however, was interestingly not a unique Rolex invention. In fact, the screw-down crown was a modification of a design submitted for Swiss patent by Paul Perregaux and Georges Perret in October of 1925. The patent was officially granted in May of 1926. When Wilsdorf heard the news, he immediately bought all of the legal rights to it in July that year. He registered the Oyster name later that month and submitted the screw-down crown for a British patent in September.

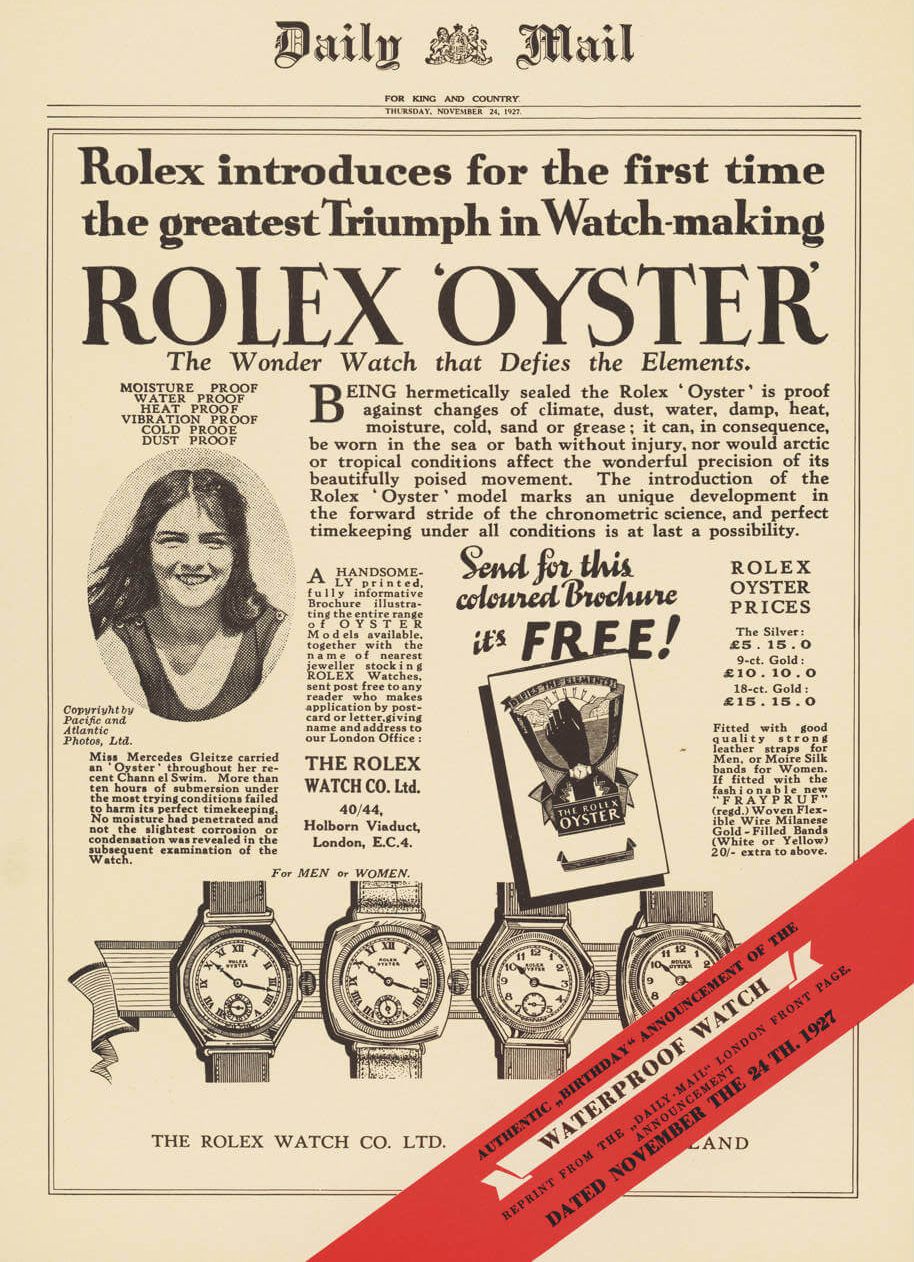

By October, Rolex engineers improved the design with a clutch to prevent the crown from winding the movement when screwing it down. Wilsdorf submitted the final design to the Swiss patent office on October 18th, 1926, bringing the Rolex Oyster to market shortly thereafter. Clearly keen to capitalize on any viable opportunity, Wilsdorf equipped swimmer Mercedes Gleitze with a Rolex Oyster for her English Channel swim on October 21st, 1927. Fixed to a necklace around Gleitze’s neck, the watch was submerged in the frigid waters for over 10 hours. Unfortunately, Gleitze did not succeed in swimming completely across the channel. The watch itself, however, kept “perfect time” throughout the duration of the swim with no moisture penetrating its case at all. Wilsdorf liberally published ads featuring Gleitze and her testimonial for years to come, making her the very first Rolex ambassador.

“The Crown” continues to innovate

Two years before Gleitze’s swim, in 1925, Wilsdorf registered the five-pointed coronet as Rolex’s trademark. In 1926, he launched a years-long (and very expensive) ad campaign aiming to raise brand awareness. Its waterproof Oyster watches enthralled passersby as they sat proudly among fish and aquatic life in tanks in dealers’ windows. After the watch accompanied Gleitze on her swim, Wilsdorf insisted that not a single product leave the company’s facilities without the Rolex name printed on the dial and inscribed both within the case and on the movement. Rolex’s reputation for rugged and reliable timepieces only grew from there, and the brand became a technology innovative force to be reckoned with. Simply producing accurate, waterproof wristwatches did not satisfy Wilsdorf, though. Rather, an absolutely critical component of his vision still remained: the perfection of the self-winding wristwatch.

Rolex intently focused its efforts on the development of an automatic movement. Designed by Rolex/Aegler’s chief technical director Emile Borer, the brand’s debut automatic caliber was the first wristwatch movement with a centrally-mounted rotor that spun 360 degrees. As detailed in my article on automatic watches, the movement was a refinement of John Harwood’s bumper automatic, which allowed for more efficient winding and a much longer power reserve. Rolex patented the technology for a maximum of 15 years, and in 1931, released its Oyster Perpetual. The watch was the brand’s second crowning achievement in less than a decade and one that Wilsdorf saw as the most logical progression of the first. He recalled, “It has been my belief that the watch of the future is the ‘perpetual’ watch… In this field too, Rolex has been a pioneer. Without the waterproof watch, the ‘Perpetual’ could never have been discovered.”

Worldwide expansion and growing popularity

Originally a London-based company, Rolex historically quoted its prices in British pounds and did most of its business within the British empire. In 1931, however, due to economic depression, the British pound suffered massive devaluation. Adjusting its prices for the pound’s new value, Rolex suffered a two-thirds decrease in total exports. In Wilsdorf’s words, this “spelled catastrophe for the firm.” Thus, the brand plunged all of its promotional efforts into worldwide markets. Rolex set up offices in Paris, Argentina, and Italy while simultaneously traveling as far as South America and Japan to establish business relationships. The brand luckily found success in the markets all over the world. Production of the Oyster increased from 2,500 to 30,000 units per year. Wilsdorf accredited this to the brand’s chronometers. Through 1939, Rolex calibers of all sizes received the best-recorded timing results from the Kew Observatory in the entire watch industry.

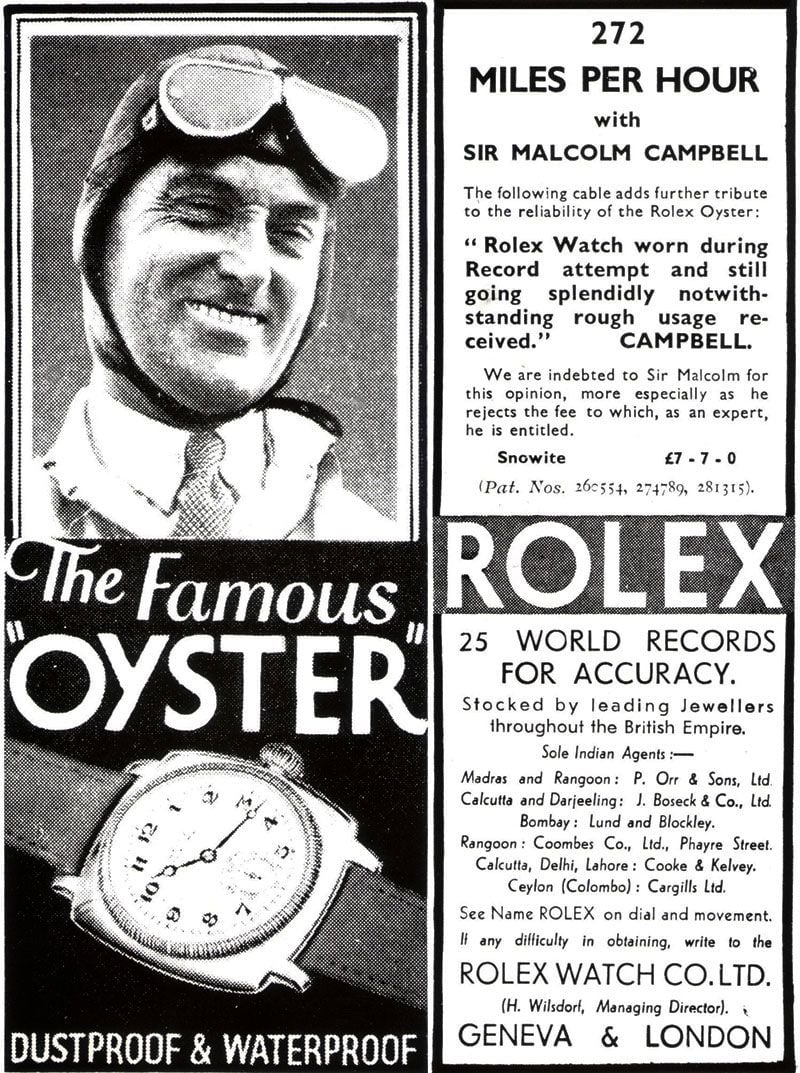

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Rolex associated itself with celebrities of the period, such as British actress Evelyn Laye. She was widely regarded as one of the most beautiful women of the time, and Rolex proudly published ads featuring her Oyster-adorned wrist plunged into a fish tank. Sir Malcolm Campbell, who broke world land speed records nine times between 1924 and 1933, was known for wearing Rolex watches. When Wilsdorf learned of this, he gained permission from Campbell to publicize it. Campbell happily endorsed the brand, believing so strongly in Rolex’s product that he refused to accept any financial compensation.

Rolex and Panerai

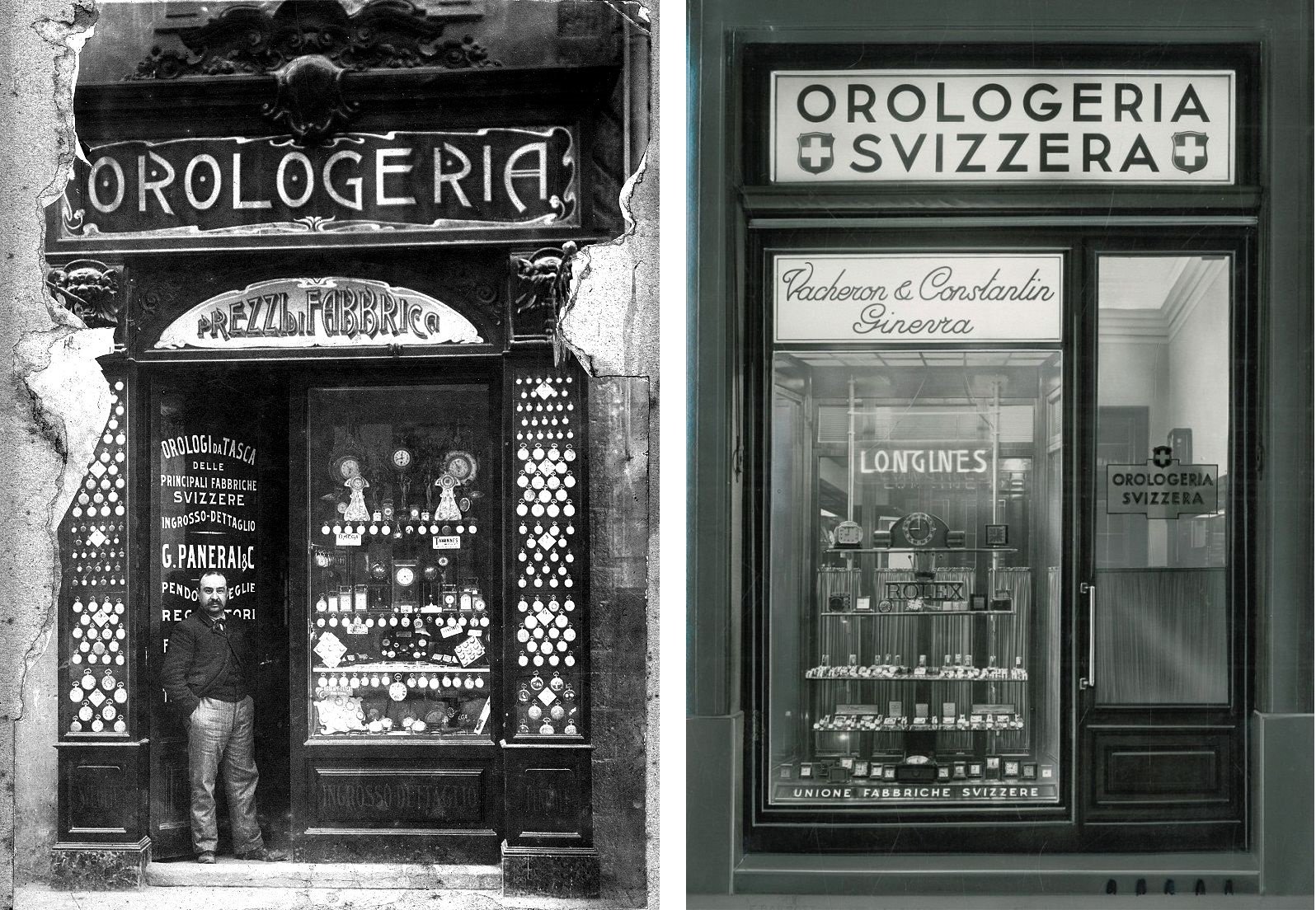

The Panerai company started as a retailer of fine Swiss watches in Florence, Italy in the mid-1800s. Giovanni Panerai opened his shop, Orologeria Svizzera, in 1860, eventually passing it to his son, Leon Francesco Panerai. Leon’s son Guido Panerai later kept the legacy alive, relocating the store to its present-day location, and opening Florence’s first watchmaking school in the 1920s. Among other brands, the store had become a trusted dealer of Rolex watches. Guido Panerai also took over his wife’s family’s business shortly after they got married, establishing the Panerai e Figlio workshop and producing various types of mechanical technical equipment. The workshop eventually became a trusted supplier of the Italian Royal Navy, providing its divers with depth gauges and compasses. Though Panerai e Figlio was adept at manufacturing this type of equipment, they had yet to manufacture any watches.

When the Italian Navy asked Panerai to provide its divers with waterproof wristwatches, the Panerai family leveraged its history as a Rolex dealer, commissioning oversize Oyster watches direct from Geneva. Rolex delivered the 9k gold 47mm Oyster reference 2533 to Panerai in Florence in 1935. Panerai approved of the design, and Rolex then produced the watches in steel. Some of these watches had unbranded “Error-Proof” (now called “California”) dials, while others featured dials produced by Panerai with its patented Radiomir luminescent compound. The cases and movements, however, were produced by Rolex until 1956.

Rolex forges on into the ’40s

Throughout the 1930s, Rolex had been doing very well internationally thanks to its patented Oyster cases and perpetual rotor-wound movements. Other brands saw Rolex’s success, and they piggybacked off of it by producing automatic bumper movements and water-resistant cases of their own. Rolex, however, remained a leader in these fields.

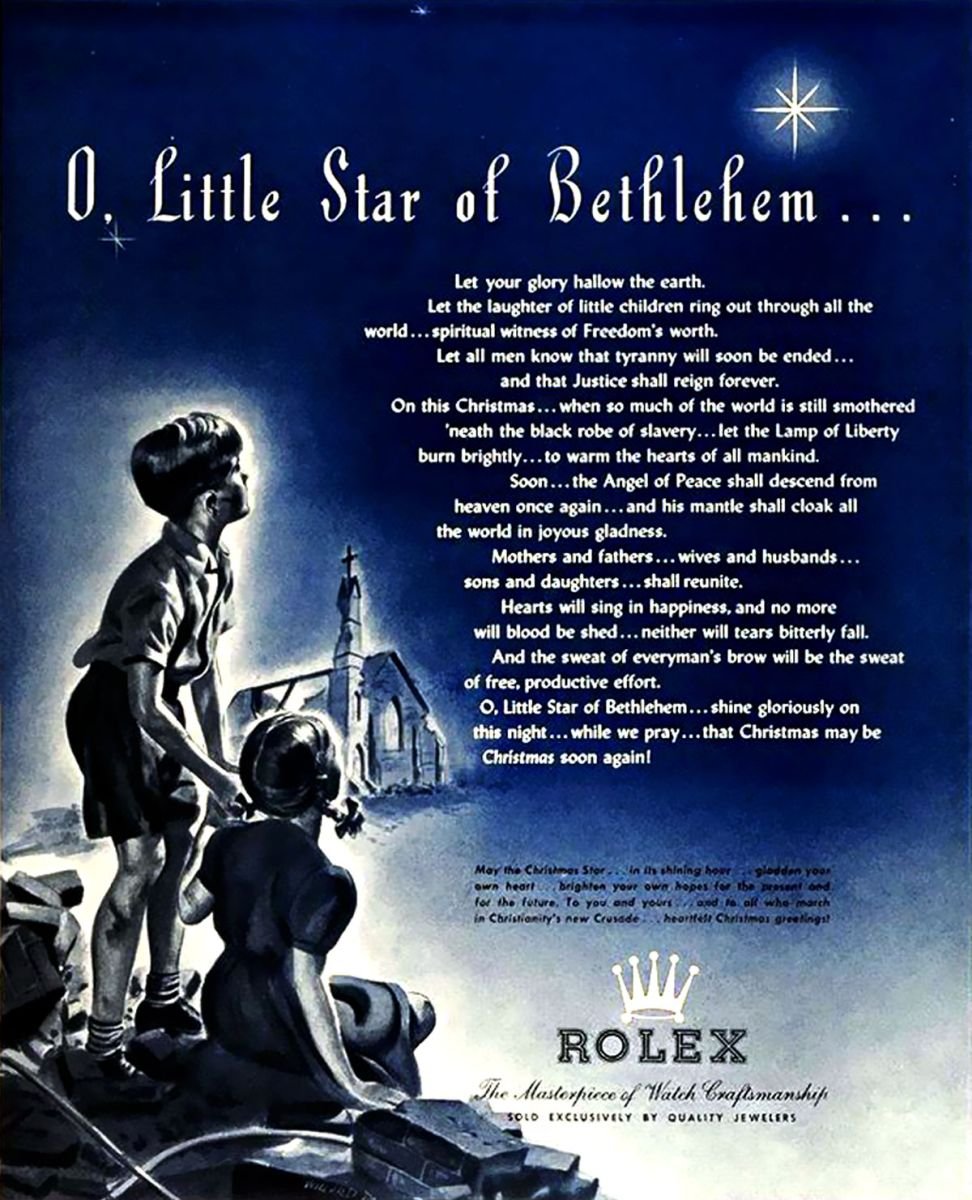

As World War II progressed throughout the early 1940s, Wilsdorf found it difficult to export his watches from Switzerland, leading to a decline in sales worldwide. During this time, however, Rolex watches became popular with soldiers, who bought them to replace their standard-issue wristwatches. Wilsdorf made a pledge to replace any POW’s Rolex watch that was confiscated in battle, not requiring any payment until the war ended. Reportedly, thousands of watches of this type were sent out to soldiers. Throughout the war, Wilsdorf promoted peace and hope in Rolex’s advertisements.

In 1944, Wilsdorf’s beloved wife passed away. The couple had no children. To both commemorate his wife and ensure Rolex’s future after his own passing, he established the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation. Upon his death, complete ownership of Rolex would pass to the foundation. Wilsdorf made his wishes explicitly clear: Rolex would neither be sold, publicly traded, nor merged with any outside entity. In memory of his wife, it would donate a large portion of its proceeds to charity, with additional funds allocated to educational institutions for watchmaking, business, science, and fine arts.

The next Rolex icon

In 1945, Rolex celebrated its 40th “Jubilee” anniversary. It marked the occasion with the introduction of the new Jubilee bracelet and the Datejust reference 4467. The 36mm watch was available exclusively in an 18k yellow gold Oyster case. Though watches with a date window, such as the Mimo (Girard-Perregaux) Mimo-Meter, had appeared in the 1930s, the Datejust was the first automatic wristwatch with this function. Its perpetual caliber 740 featured a unique “roulette” date wheel with alternating black and red numerals. It also featured a central seconds hand, which was quite rare at the time. Since 1945, the Datejust has never once left the Rolex catalog. Through the years, it has truly evolved into one of the brand’s most recognizable designs.

Just the beginning

In its first 40 years in business, Rolex had risen from nothing but Wilsdorf’s vision of a wristwatch-wearing world to one of the industry’s foremost watch manufacturers. It had made massive strides in improving wristwatch accuracy, durability, and water resistance. It had proved to the traditionalist Swiss watch industry that indeed fortune favors the bold. Most importantly of all, Rolex had shown no signs of slowing down. In the decade to come, Rolex would release some of its most capable, desirable watches to this very day.

But we’ll save that for Part Two. Join us back here in two weeks for the next installment in the history of Rolex!