The Man Who Skied Down Everest With A Certina DS-2 Watch

Yuichiro Miura’s 1970 expedition to Mt. Everest was the subject of a documentary and press coverage, and it became a legend in the extreme skiing community. His companion on that adventure was the Certina DS-2 Chronolympic. It was a hardy chronograph built for adventure.

There is a way of considering the world’s tallest peaks that resonates with the adventurer in me. Watching the award-winning 2006 documentary Planet Earth, narrated by the great Sir David Attenborough, is when I first heard it. In one episode, focused on mountains, he described those fearsome and majestic peaks above 20,000 feet high as “the roof of the world.”

It has always stuck with me as a poetic summation of how forbidding and alien that environment can be, as Sir David Attenborough notes in the series.“Human beings venture into the highest parts of our planet at their peril. Some might think that by climbing a great mountain they may somehow have conquered it. But we can only be visitors here.”

The roof of the world

For those who dare to enter the frozen, alien world of very high mountains, there is a vast array of dangers to navigate. These include avoiding avalanches, falling rocks, or falling ice. One encounter with an avalanche would most likely be fatal. Then there is the wind. Tempests of 160 km/h (100 mph) can buffet climbers in the Himalayas. This is because mountains that are close to 30,000 feet start to jut up into the earth’s jet stream. This area of the earth’s atmosphere is where extremely fast winds travel.

Then there is one of the most insidious dangers of all — battling fatigue and exhaustion because of the low levels of oxygen and extremely high altitudes you’re exposing your body to. Even seasoned climbers succumb to these effects if they’re not careful. Hypothermia because of the extreme cold can also inhibit your decision-making abilities. This can happen just when you need them most.

The number of different things that can kill you at these high altitudes led one Swiss doctor, Edouard Wyss-Dunant, to name the area above 8,000 meters (~26,245) feet as the “death zone.” It is called such because it is roughly the point at which life without external assistance and specialized equipment, like oxygen tanks, cannot be sustained for long. Oxygen pressure at these heights is not sufficient to sustain a human being. All 14 mountains towering above this death zone of 8,000 meters are in the Karakoram and Himalaya mountain ranges.

Yuichiro Miura and his Mt. Everest adventure

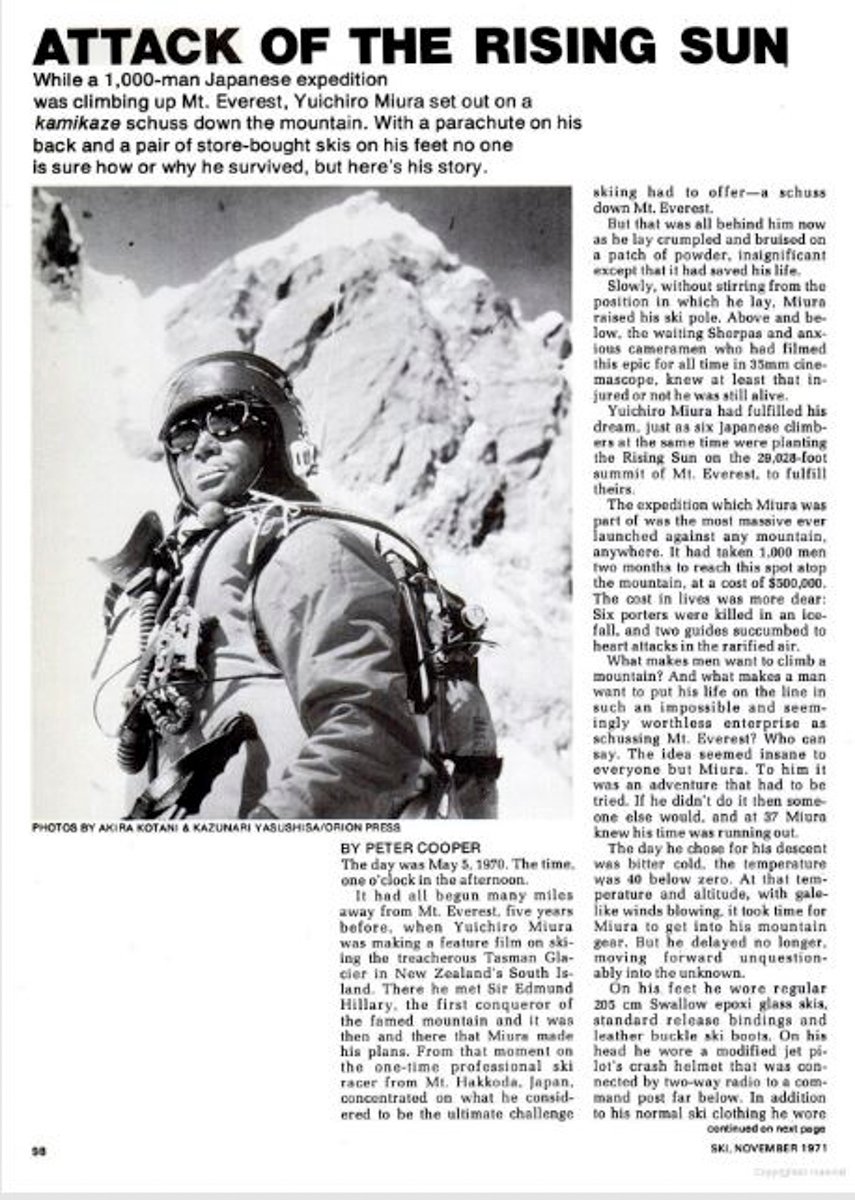

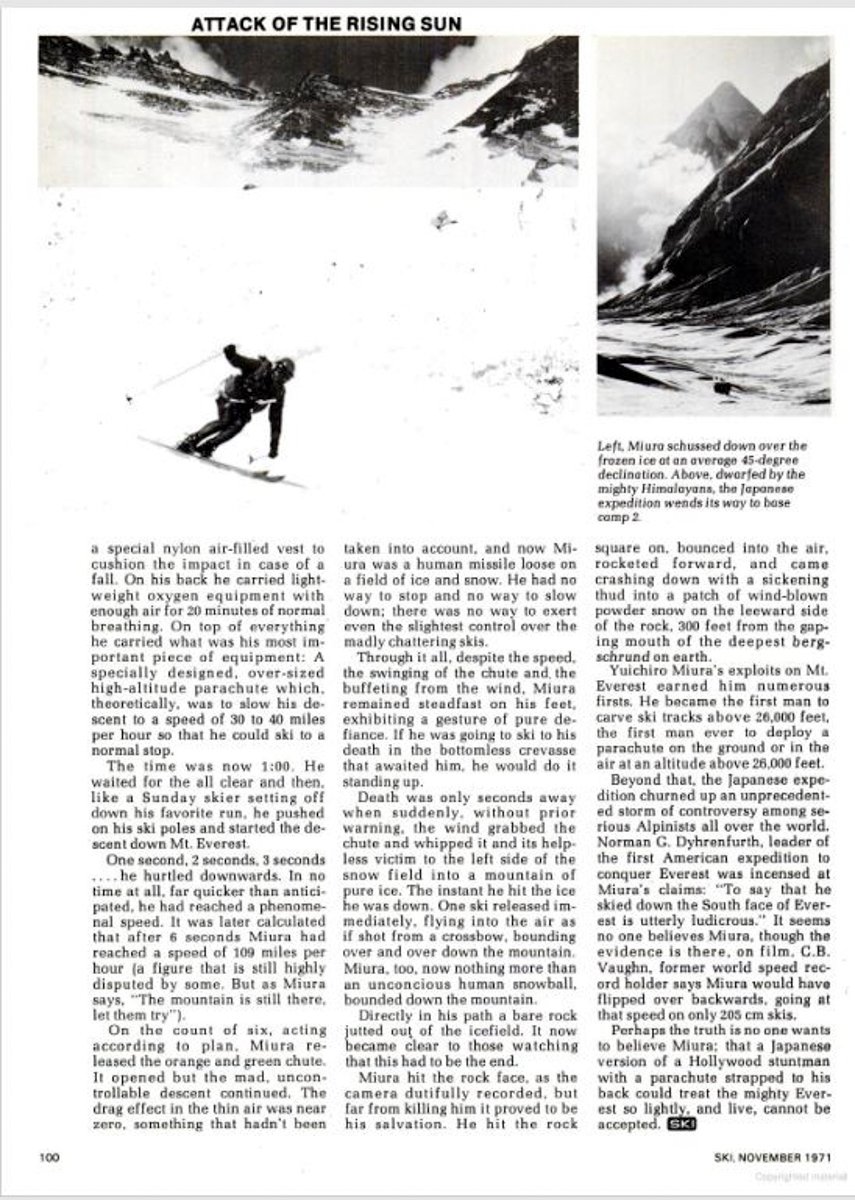

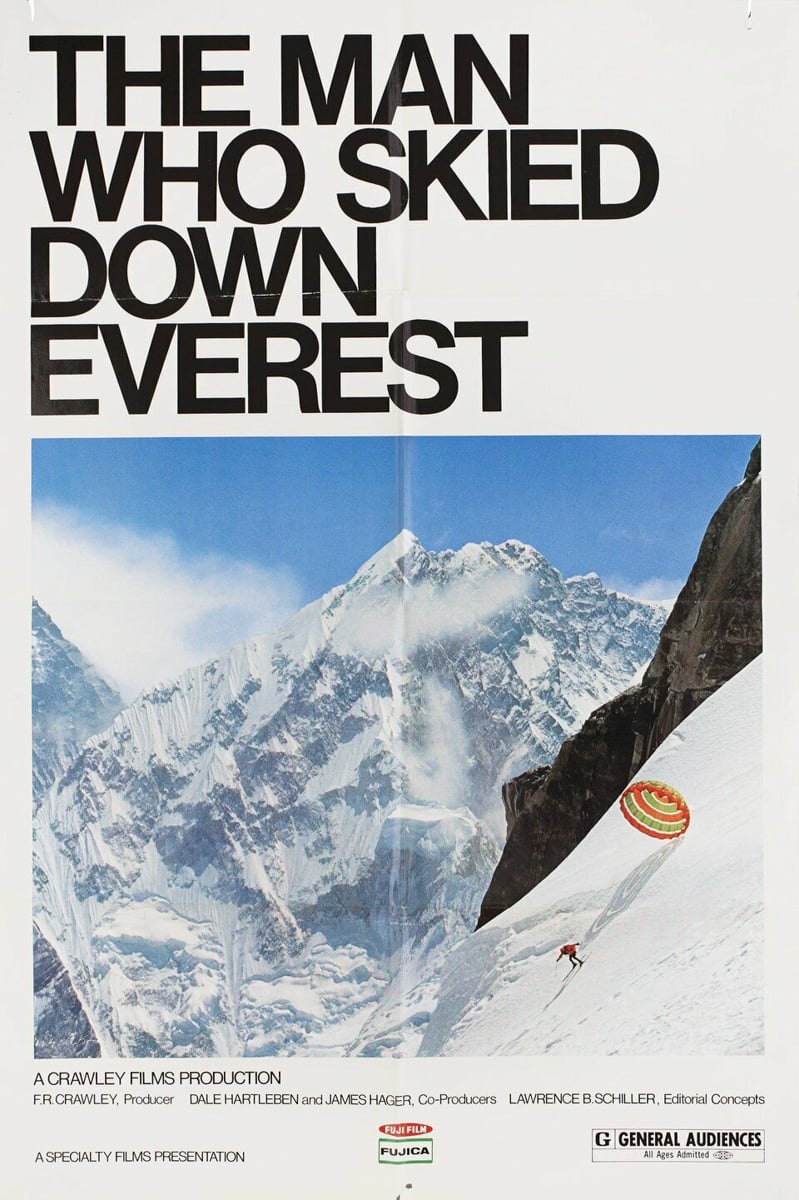

In 1970, a Japanese expedition entered this forbidden world. These men had one objective — to have one of their company, Yuichiro Miura, descend Mt. Everest on skis. Fellow veterans of adventure accompanied the extreme skier. A documentary crew also accompanied them. The filmmakers would turn this Japanese expedition into an Oscar award-winning film, The Man Who Skied Down Everest.

It sounded like a mad plan. Miura, with a fighter pilot’s crash helmet strapped to his head, goggles, his lips smeared with a protective film of sunblock for high-speed skiing in a frozen world, would descend at such fast speeds that he would need a parachute to maintain a degree of control. They did not even know if the parachute would work properly because of how thin the air was at that altitude. Miura recounted later that he thought his death was almost a certainty. A moment, a breath, and he pushed off down the sheer 45-degree slope.

A Japanese explorer’s beginnings

If there was one who could pull off this mad feat, it was Miura. By the time of his 1970 expedition, Miura was no stranger to extreme quests. In 1964, he had set a world record for high-speed skiing at a blistering 172 km/h. In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Miura recounted this moment. “It was a wonderful feeling that I was able to set the record but I knew the record was meant to be broken.” The record was broken in the end, it turned out…one day after Miura’s record-setting moment. But it did not matter as Miura had developed a taste (or obsession) for extreme skiing.

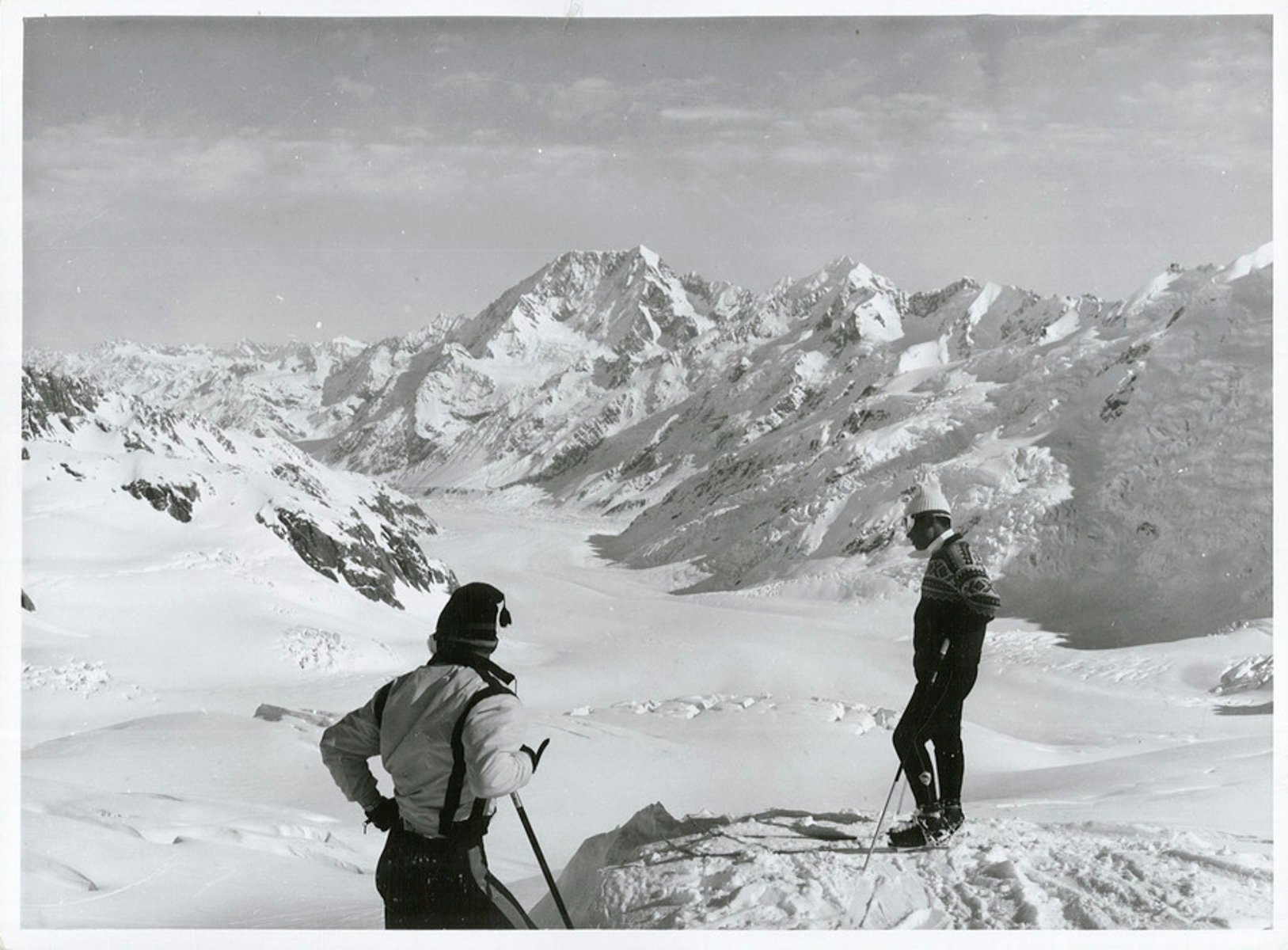

After his 1964 accomplishment, Miura went on to ski down some of the world’s most famous mountains. This included Mt. Fuji in 1966. In 1967, he then skied down Australia’s Mt. Kosciusko and Mt. McKinley in the United States. According to government records, New Zealand’s Bureau of Tourism also invited Miura to ski down the Tasman Glacier. The Tasman Glacier is the largest of its kind in New Zealand, being (as of now) more than 23 kilometers long, four kilometers wide, and 600 meters thick!

An Everest journey

While in New Zealand, Miura met fellow explorer Sir Edmund Hillary, who climbed Mt. Everest to its summit with Tenzing Norgay in 1953. Miura told Smithsonian Magazine, “Sir Edmund Hillary was my superhero. When I listened to his Everest summit, I determined my target to be Everest, too. He inspired me to be an extreme skier who can make history.” Like Sir Hillary, Miura would enter Mt. Everest folklore.

The government of Nepal had been open to the idea of Miura’s incredible attempt (government permission was a prerequisite). But the government had stipulated a condition: the expedition would be allowed to ski down South Col only but not the mountain’s summit. South Col connects Everest with Lhotse (the fourth-highest mountain on earth). The 45-degree angled slopes, Miura told Smithsonian Magazine, would be suitable for his skiing attempt. But a realization had crept in that he faced a likely death in his attempt. “When I planned to ski Everest, the first thing I faced was ‘How can I return alive?’ All the preparation and training was based on this question. But the more I prepared, [the more] I knew the chance of survival was very slim. Nobody in the world had done this before, so I told myself that I must face death.”

A diverse team

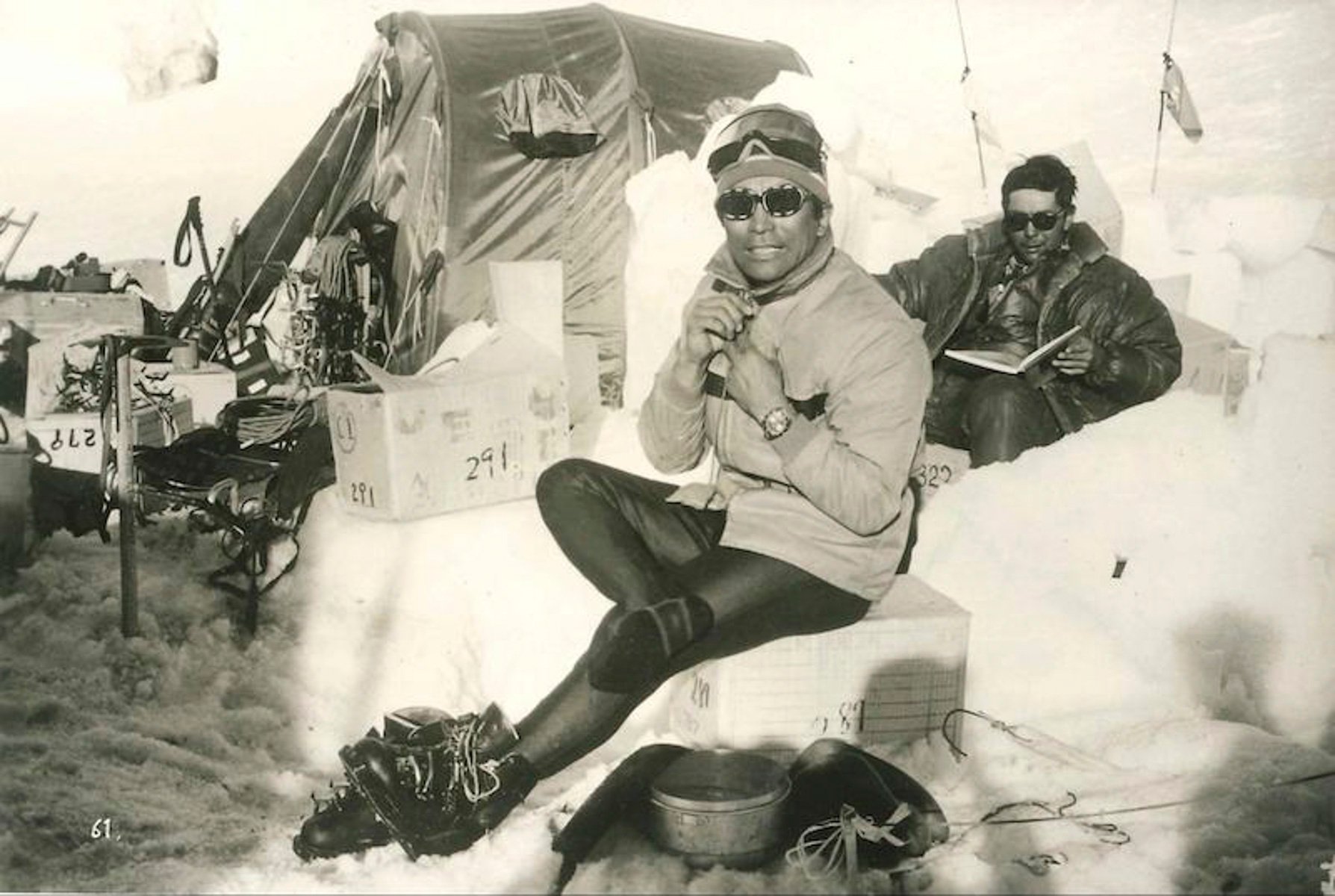

The team that went to Mt. Everest in February 1970 was a motley crew of alpine experts, mountaineers, scientists, skiers, a film crew with photographers, and journalists. According to records, more than 25 tons of equipment was taken (some accounts state that it was 27 tons), and, according to interviews, 800 porters were needed to take this to the Everest base camp (although some magazine features state that up to 1,000 people were involved).

When considering the amount of gear necessary, including documentary-making equipment, this figure starts to make a lot of sense. In press clippings from the time, it was noted that the 185-mile journey to base camp took 22 days to complete.

An expedition not without cost

The expedition’s members had to get used to the much thinner air at base camp. The altitude they were now living in was approximately 17,500 feet (~5,334 meters). This meant that the oxygen levels were as little as half of what they were used to on the ground. They spent several weeks acclimatizing and preparing for the next phase of their journey. Miura spent this time with his compatriots working up his ski attempt. He did test runs with and without a parachute to see how it performed at this high altitude where the air was thinner.

It was at this stage that the journey had its first casualties. First, two people suffered heart attacks because of the thin air. Both ended up being fatal. Then, a cave-in on the infamous Khumbu Icefall left six Sherpa dead. According to later interviews, it was at these low points that Miura seriously considered abandoning the attempt altogether.

The final push…and then the rush

Miura and his team kept training. It was good that they did because the next phase of their adventure would be one of the most challenging. The morning of May 6th arrived. It would turn out to be the day that provided the right conditions for his descent. He started with a few practice turns on South Col’s slope. He was now the first human being to ski at an altitude of more than 26,000 feet (~7,925 meters).

But the conditions went south. By 11 o’clock that morning, strong winds had picked up. The winds were too strong for him to deploy his parachute. But if he didn’t try, he would have to wait days for his next opportunity. He, the film crew, and his fellow adventurers decided to wait a little longer just in case. Then, at around 1 o’clock the winds started to die down, and 8,000 feet (~2,448 meters) below, the people at the control center began preparing. They would monitor Miura’s descent, and cameras equipped with long lenses would try to pick up his hurtling journey downward. Within that 8,000-foot space, expedition members spread out to rescue Miura if something were to go drastically wrong.

Six seconds from the start of Miura’s descent, the 37-year-old would already be traveling at 160 km/h (~100 mph). He could not get this wrong. In the documentary, you can hear Miura breathing rapidly into his oxygen tank moments before his descent, a reflection of the Himalayas in his goggles.

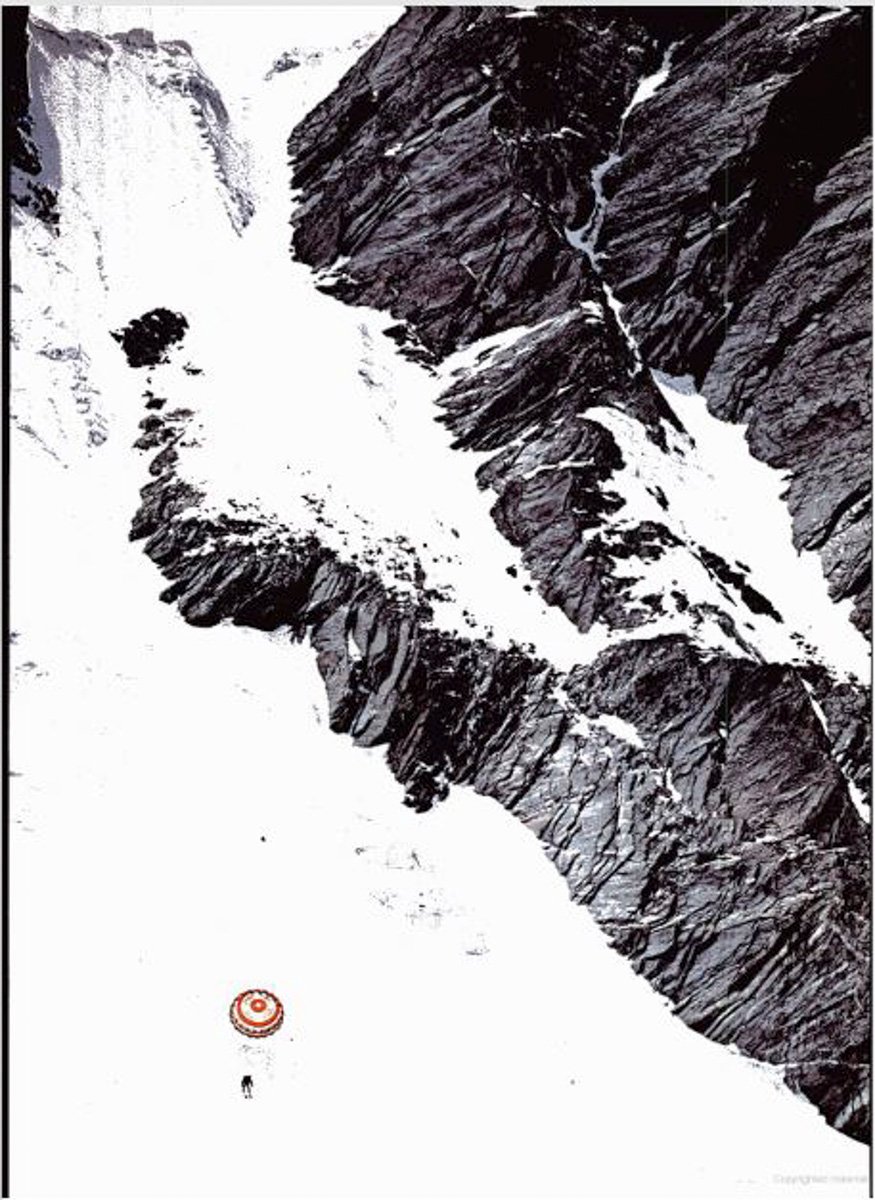

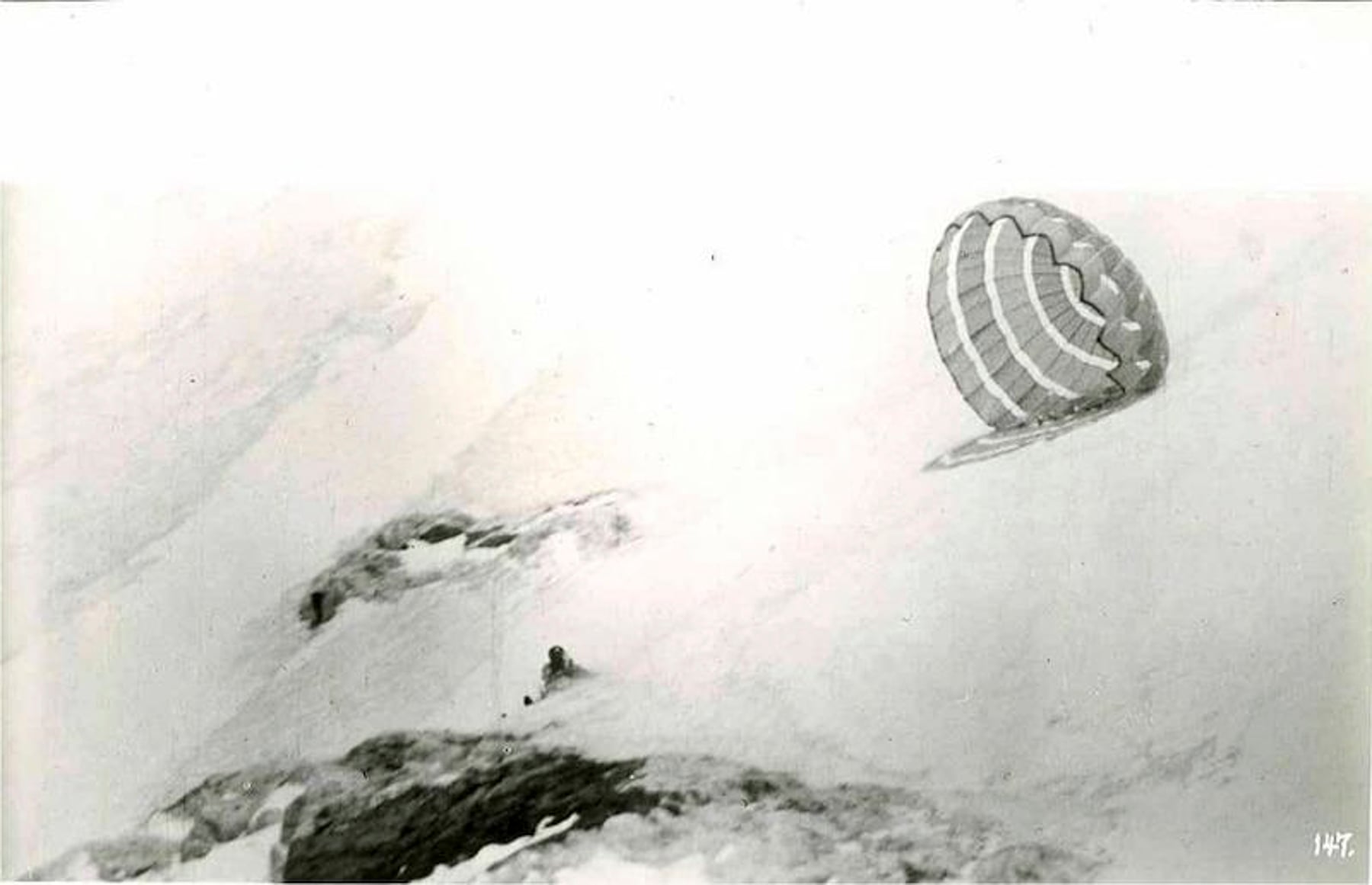

At 1:07 PM, he pushed off. Within seconds, he deployed his parachute to try to bring his speed under control. But erratic currents had returned, and the wind was buffeting his chute. In an interview afterward, Miura said, “The strong turbulence, the direction of the wind, and its strength were constantly changing, so it was very hard to keep balance.” Miura’s parachute was doing nothing to help him stay in control.

The moment comes: A breath, a clatter, and whoosh

Less than 30 seconds into his descent, Miura’s teeth must be shaking in his head. The skis are clattering across rough ice. In the documentary, you can see him use everything he can to try and regain control. He starts zigzagging down the slope. His legs maneuver and bounce like pogo sticks, desperately acting as a suspension to the rough ground. His legs splay, then tighten up closer together, then splay again as he wrestles with the unsteady ground beneath him. Then a ski catches on a rock, and he’s no longer skiing. He’s falling. His left arm is outstretched behind him, his legs at an angle — anything to slow down.

Miura later recounted these terrifying moments: “I was 99 percent sure I would not survive.” His skis were released, but the safety straps kept them connected to his body, and they started whipping around uncontrollably. In the documentary, you see one suddenly snap and bounce away with what must have been a huge force. Miura has to try and come to a stop. One of the world’s largest crevasses is looming closer and closer. He suddenly hits a rock, falls off its ledge, and slides down into a patch of snow. He has stopped just 250 feet (~76 meters) short of the crevasse. He’s limp for a while and then starts waving. He’s alive. He later described these moments after coming to a stop as “the soul returning to my body.”

The descent and future summits

In just two minutes and 20 seconds, Miura descended around 4,200 vertical feet (~1,280 meters). It wouldn’t be his last dance with death. In 1981, he skied Africa’s Mt. Kilimanjaro, and in 1983, he was the first person to ski Antarctica’s Mt. Vinson. Then, in 1985, he went to Russia and skied down Mt. Elbrus.

It would not be his last journey to Mt. Everest either. After many years of preparation, the then-70-year-old Miura hiked to the summit, getting to the top on May 22nd, 2003. He was the oldest known person to have summited Mt. Everest up to that time. Five years later, he summited Everest again. Finally, at the age of 80, Miura summited Everest for a third time in 2013.

Yuichiro Miura, then 80 years old, making his way to the summit of Mt. Everest in 2013 — Image: Miura Dolphins

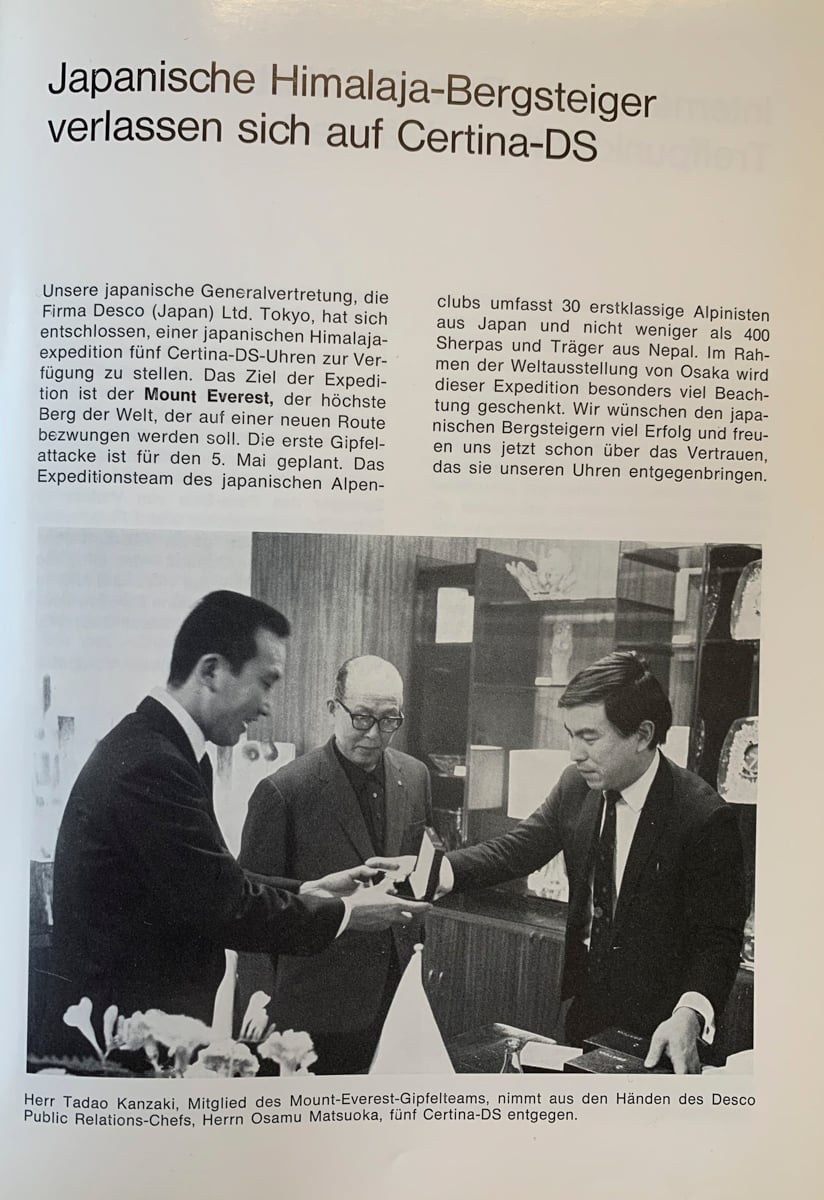

The Certina DS-2 Chronolympic

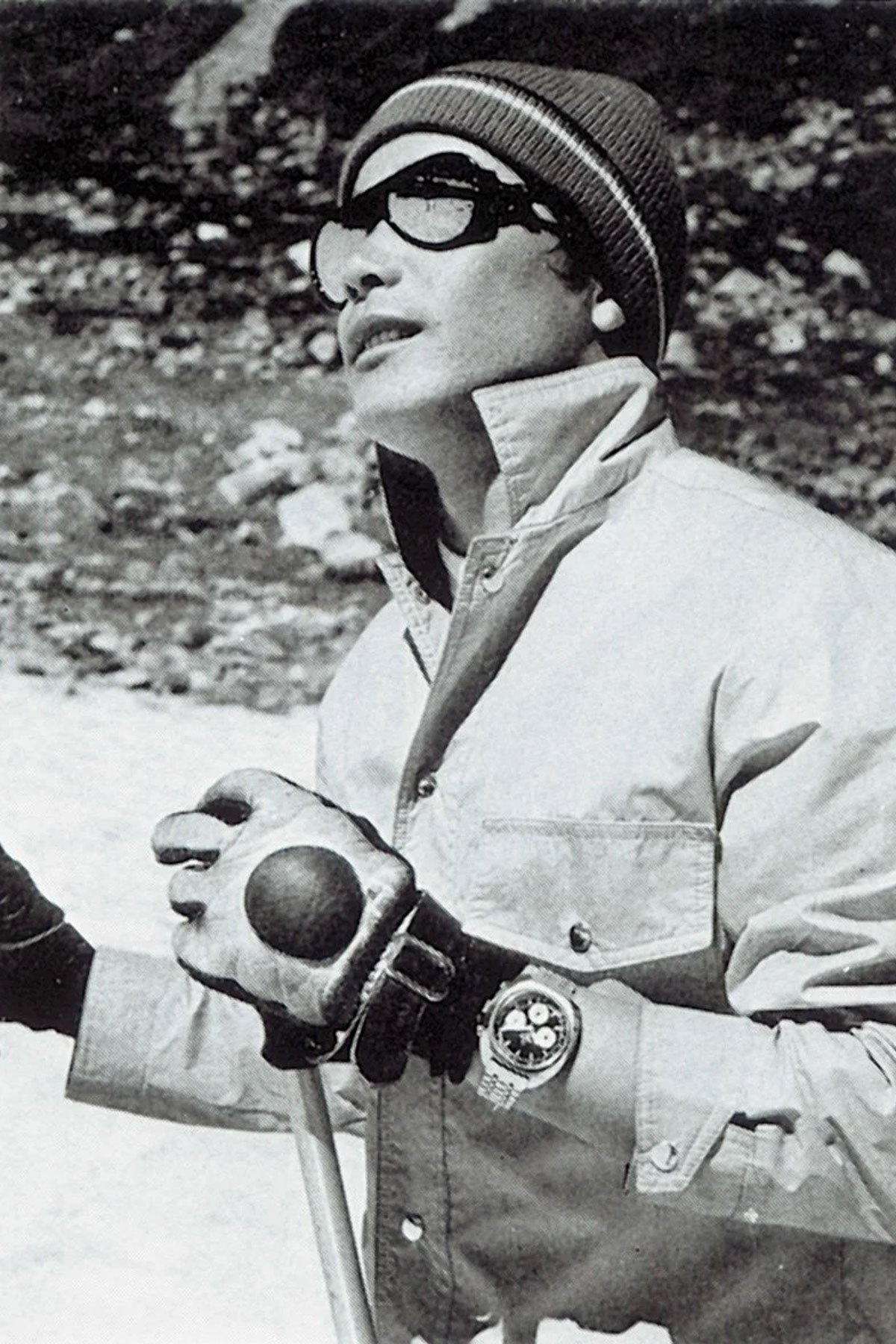

A great adventure such as this deserves a great horological companion. Miura’s watch for his incredible 1970 journey was the Certina DS-2 Chronolympic. According to the website vintagecertinas.ch, it was the reference 8501 800. In screenshots taken from the documentary (below), you can see the Certina DS-2 Chronolympic on Miura’s wrist. Interestingly, it looks like a double-register and not a triple-register model. In press shots, Miura wore a triple-register Certina DS-2 Chronolympic, so perhaps the camera angle affected the view.

- Screenshot: The Man Who Skied Down Everest

- Screenshot: The Man Who Skied Down Everest

- Screenshot: The Man Who Skied Down Everest

According to an article in the Certina archive, which the company shared with Fratello, Certina’s representative in Japan presented Certina watches to the expedition. No doubt, there will be some German readers among us who can learn more. The article mentions that Certina representative Desco (Japan) Ltd. provided five Certina DS watches to Miura’s team. Translated, an excerpt states, “This expedition is receiving particular attention as part of the Osaka World Expo. We wish the Japanese mountaineers much success and are already pleased about the trust they have placed in our watches.” We thank the folks at Certina for providing this helpful excerpt from their archive.

The Certina “DS” concept

Certina had been manufacturing rugged timepieces using the DS (Double Security) concept since the late 1950s. As a previous Fratello article that I wrote on the DS design states, “This meant that the watch movement would be ‘floating’ inside the case thanks to an elastic shock-absorbing ring in addition to an Incabloc shock absorber inside the movement. Furthermore, there was a gap between the dial and the case so that the movement could physically move in all directions.”

Certina’s DS-1 had already seen action in the Himalayas. In a 1960 expedition, a Swiss team took the watches there and climbed to the peak of Dhaulagiri, which is 26,795 feet (8,167 meters) high. Therefore, Certina can claim serious mountaineering credentials. Indeed, Certina is also a brand with a fascinating range of backstories.

A new version of this classic Certina DS-2 Chronolympic

Recently, Certina brought back a modern rendition of the DS-2 Chronolympic. However, it does not have the tri-register layout of the DS-2 that Miura took to Mt. Everest. Rather, it is based on a bi-register Chronolympic produced in the 1970s. It would be wonderful to see a tri-register model released that closely resembles the watches taken on Miura’s Himalayan expedition.

As we can see above in this image from Analog:Shift, the Certina DS-2 in its tri-register format was an attractive and burly chronograph. There is something quite wonderful about the chronographs of this era. The version that Miura wore had a black dial with white sub-registers. The DS technology would have surely been put to the test with Miura’s teeth-shattering descent!

A Certina DS-2 Chronolympic with a wonderful backstory

It is wonderful to have a modern watch (and one that closely resembles the original) with such an incredible backstory. That said, the differences between the original 1970s versions and the modern ones are significant. Straight away, the heft of the new model can be felt. The new Certina DS-2 Chronolympic is slightly larger than the original with a 43.3mm case diameter, a 48mm lug-to-lug, and 20mm lug spacing. The case is 15.8mm thick, including a tall domed sapphire crystal (which accounts for nearly 3mm of the thickness). In these photos, you can see a vintage example compared with the modern Certina DS-2 Chronolympic.

In the spirit of the durable design ethos of the original, the new Certina DS-2 Chronolympic has a 200m water resistance rating. Unlike the original, it also has a screw-down crown, a welcome advancement. One thing I miss having on this new watch is the wonderful turtle design on the case back of vintage Certina models. Some modern Certina watches do have it, and it is a symbol of the durability of these watches. Another thing I miss about the originals is the handset, use of the term “Chronolympic,” smaller date window, and better dial color. The lighter blue just seems more alive.

A Certina DS-2 Chronolympic worthy of its heritage

However, the modern Certina DS-2 benefits from technical innovations in movement technology. It boasts the ETA A05.231 automatic chronograph movement. This equips the watch with an antimagnetic silicon hairspring and provides a solid 68-hour power reserve. The movement is visible through an exhibition case back, though, as mentioned, I would rather see a solid case back with the Certina turtle here.

Setting the date requires using a recessed pusher at the 10 o’clock position on the side of the watch. Because of this, the screw-down crown pulls out to a single time-setting position, hacking the seconds hand. I get an overall impression of a hefty, well-made, and thoroughly tough modern mechanical chronograph when handling the DS-2. However, I do find that the vintage model’s slightly smaller dimensions fit my small wrist better. Generally speaking, this new Certina DS-2 is a worthy rendition of its vintage ancestors. But I would like to see a Miura special edition or “MKII” that more closely reflects the original. And a three-register version would be awesome! This would be something that I could wear with my smaller wrists (if it shared dimensions). Certina, if you’re reading, please take note!

Final thoughts

Miura was an amazing adventurer. He cared deeply about the lives of his teammates (he considered abandoning his 1970 expedition when six Sherpas were killed and he lost two men to heart attacks). While caring deeply about the lives of others, he seemed to almost treat his with reckless abandon. But I believe this was because of his philosophy for how he would live, not due to any sense of ego.

Miura’s long list of adventures stands as a beacon for those of us who, even if it is a small step outside, want to get out of our comfort zone. For that and his passion and love of skiing, Miura is an amazing character. It is wonderful that he had a trusty Certina watch strapped to his wrist during his awe-inspiring Everest adventure over 50 years ago. But perhaps even more wonderfully, his adventures continue.