Haute Horology Enjoyed From A Distance: Why A Patek Philippe Isn’t For Everyone

Let’s face it: most of us are never going to own a Patek Philippe. Most of us will never own an Hublot. If we’re being realistic, most of us watch aficionados may never even own a Rolex either. I’m here to tell you that’s okay. Really. It may, in fact, be good. We shouldn’t strive to own everything we appreciate, and we should be mindful of what is lost in attaining these luxury and hyper-luxury watches.

The hype machine is in full force. I blame Instagram. I blame YouTube. And I blame publications like us at Fratello and the rest. But really I blame us, the public, the consuming watch market. We’re adrift in a perfect storm of ingrained FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) blended with algorithm-driven envy via every digital turn we take. The watch industry, like any other, has taken full advantage of social media ambassador marketing and targeted ads. The product placement we grew up with, namely in movies, has expanded to encompass every aspect of the information realm.

The state of luxury watch marketing

This aspect of lifestyle attainment culture mixed with constant oneupmanship has led to a watch industry still offering a full spectrum of price points, but a marketing realm heavily weighted to the hyper-luxury and the hyped (I’m looking at you Rolex). Even watches that were relatively inexpensive upon release, if they get the hype treatment, can more than double in price on the “gray market” or used.

And so, from this, we have been led to believe that all of us should strive to attain the best, and that nothing less is acceptable as an endpoint for our collections. But what is best is being dictated by those that make “the best” watches, and even more so by those that consume them publicly. To own expensive watches as a drive to attain and appreciate “the best” is not toxic in and of itself. The blanket assumption that what’s best for those that can “pay to play” is also the best for everyone is toxic. Their best is not everyone’s best, no matter how nice the watches may be.

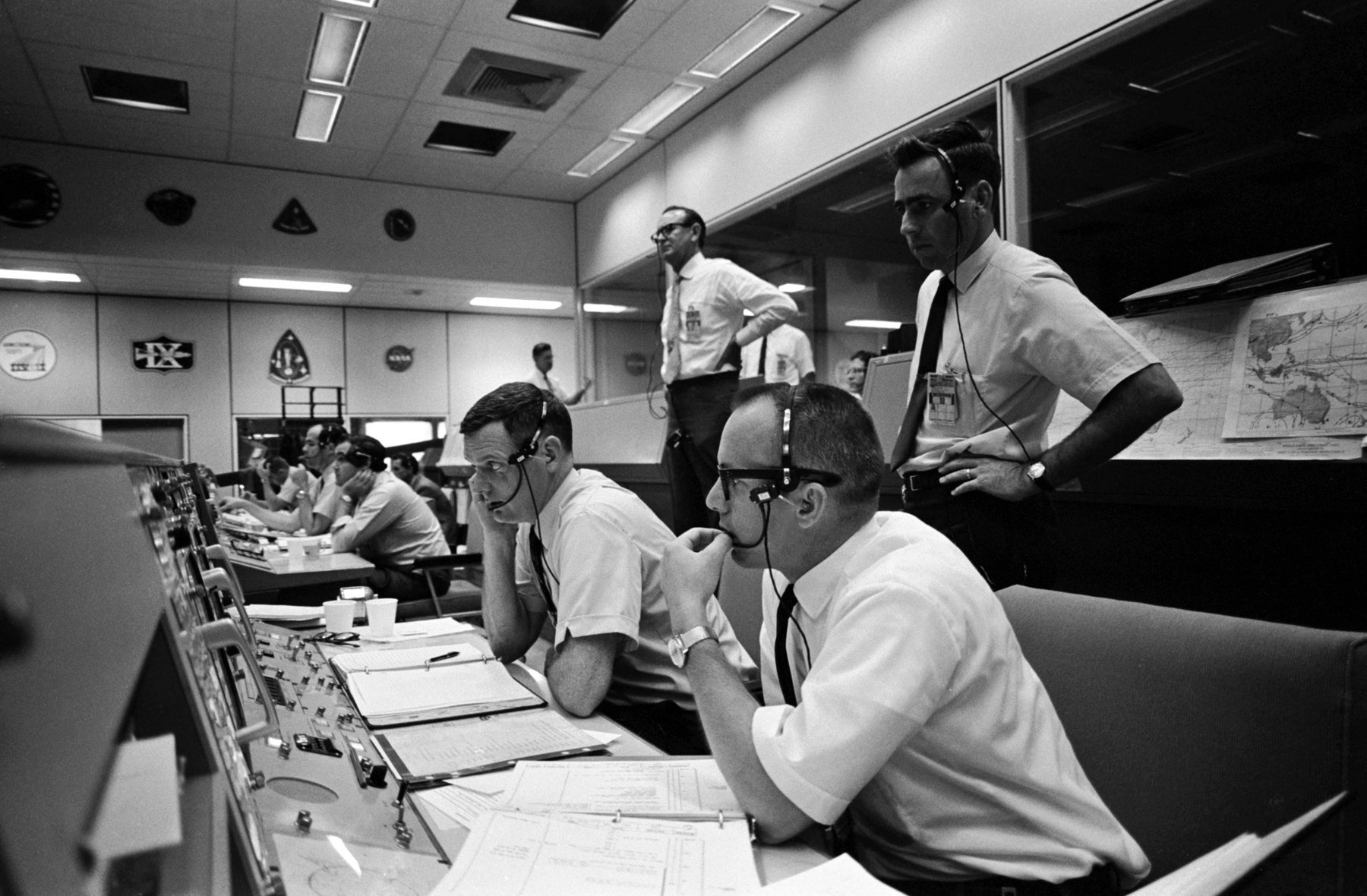

NASA’s Mission Control during the Apollo 10 mission. Extra points for identifying every watch. Courtesy of NASA

The end of a Golden Age

Really, the beginning of this fiasco occurred decades ago, before this mess of social media marketing and hype culture. It was with the transition of watches as tools to watches as toys that initiated the downward slide. Before the departure from standard workplace attire and the proliferation of cell phones (which tell the time adequately), the watch existed in just about every professional adult’s life as a necessary tool. It fulfilled a social contract as an element of attire that projected a sense of responsibility. More importantly, it told the time, very important in an industrialized world not yet digitally saturated with information.

No one wants to talk to a man with a shoebox full of polaroids.

We can’t ignore the use of the watch as a status symbol, as that has been an aspect of personal timepieces since their earliest iterations. But in pre-internet days, only one watch worn at a time could assert status. It was much more difficult to show people how many nice watches someone owned without smartphones. No one wants to talk to a man with a shoebox full of polaroids.

This heyday of watch-wearing — post-industrial revolution, pre-digital — naturally resulted in a balance. Watches were expected to be worn. Owning lots of watches was a superfluous flex few participated in. Yet watches were still status symbols. What ensued was people gravitating to watches that fit their career and lifestyles, and that transmitted their desired status. Those watches people wore were the best watches, for them, because they worked for them.

The modern watch “collecting”

Much of the developed world has lost that magic of the right watch for the right person, which was taken for granted when watches still functioned as tools. Watch collecting, the mode of ownership we have now, imparts a schizophrenic kaleidoscope to the relationships we have with watches, the relationships the current industry was built upon. Instead of the right watch for the right person, we have a drive to have many watches, and the need to be the “best”.

For some, it’s as simple as expressing different moods or matching different outfits, as jewelry does. For others, most I would guess, watch collecting has an element of touching, owning, and displaying the prestige that the different watches we lust for embody. “Rolex” means more now than it did when it was more a very good watch and less of a flex. Don’t believe me? Explain to me how ever-increasing luxury watch prices actually translate to the value and production costs of the watch. We are paying for prestige. A very good watch just happens to accompany it.

We must acknowledge the good the transition to watches as something to collect has done for the industry. It saved the mechanical watch from almost certain destruction by the Quartz Crisis. It was exactly the untouchable mixture of prestige, exclusivity, and anachronism that kept watch buyers, well, buying. At this point, that transition has gone above and beyond to make the watch industry very wealthy indeed. See my point on prices above.

Rage with the machine

Now the industry and public keep the machine going. Companies keep churning out watches full of “wow” and prestige in a bid to catch the public’s attention. Prestige is determined by a combination of craftsmanship, exclusivity, materials, technology, history, and public hype. We strive to own the watches we dare to dream of ourselves with. It’s still a form of right watch for the right person, as we pick Submariner over Speedmaster, but the element of practicality — for our lifestyles, for our incomes, for our personal tastes even — has gone out the window. We ceased striving to become the intrepid “every-man” (or woman) of yesterday whose watch choices helped forge the prestige today’s watch brands are imbued with. Now we hope our forbearer’s prestige will wear off on us by owning the watches and brands they wore.

How nice is “too nice”?

That’s one aspect of the problem. Another side, involving the crème de la crème of horology, embodies a different personality crisis. I once longed for a Patek Phillipe reference 5327R Perpetual Calendar in Rose Gold. I would imagine owning one, gazing at it adoringly under a loupe, and… not much else. Because when I imagined myself with that watch, I could only see myself indoors, secure in my (fantasy) house.

I’m happy to not be burdened with things I’m terrified to break or lose.

I don’t move in the realms that are conducive to owning a watch that cost more than my first home. I’m no titan of industry, noble, or movie producer. I don’t want to be, I don’t want that life. I found myself unable to imagine myself owning that watch because I, in all that I am, cannot comfortably own that watch. This sentiment exists outside of personal finances. I am who I am; my life is my own making. I’m happy to not be burdened with things I’m terrified to break or lose.

Yet I still love these watches — the best watches — we all do. It is these paragons of watchmaking that astound us, captivate us, and continue the conversation and progress in what is good, true, beautiful (or garish), and possible in a watch. And we must come to terms with the fact that almost all of us will never own any of them.

Auctions for the rich, museums for none

We lovers of high horology are devoid of resources to enjoy the watches we love without ownership. That is the real tragedy. Unlike history, music, and especially art, there aren’t halls and museums in every metropolitan area where we can go enjoy what is truly an art. Watch museums are sparse. Watch conventions and talks are few and far between, often with entry fees no art museum would think of charging. There is no concept of public ownership of the best watches that comprise history and the contemporary. As consumer goods based on exclusivity, even their distanced enjoyment comes at a price, if at all.

Digital spaces

We are lucky that publications like Fratello exist. The online watch publications and forums are our virtual museums, our virtual conferences. It is through the internet that my love for horology sparked and continues to expand. True, these digital spaces, free to the public, are funded by the same industry that benefits from and feeds into the current state of hype; they are an extension of it. But we are two peas in a pod, aficionados and industry. Each needs the other, and neither watch lover nor watch industry can exist without its counterpart. I am thankful we have these spaces to lament the current state of luxury watches while we still gush over the newest releases.

Gerhard Richter, German painter of international renown and at one point the highest valued living painter in history (not highest paid, mind you), when regarding his own work hanging on museum walls said, “I would prefer to see it in a museum. Then I am immediately happy. Not in a private collection. It’s not good when this is the value of a house. It’s not fair. I like it, but it’s not a house.”

What’s in a price?

The world of modern art and the watch industry are not so different, especially in recent decades. There is an inherent cost to every painting — the canvas, paints, and the painter’s time and energy. This is true for a watch as well — materials, labor, and company overhead are the equivalents. The cost to the consumer, however, is based on less tangible elements. “Perceived value” is a blanket term that encompasses all the je ne sais quoi that goes into what the public thinks the value is, and consequently what can be charged. It comes down to supply and demand — how many pieces there are, how many people want it, and how much they are willing to pay to get it.

I expect certain players in the watch industry would be thrilled if watch values were completely disconnected from material value and relied only on perceived value, as art does. Thank goodness we haven’t gone there yet. Richter said, “Money is dirty”. I can agree with the sentiment in a vacuum. In the realm of watchmaking, however, where value is still tied to actual material costs of development and production, money is the fuel that keeps the machine going.

Almighty Money

In actuality, we need people willing to buy watches — any watches, at any price point — but especially the watches that define and drive the industry. I hope that the watch bubble will not burst, but perhaps deflate some, and that the rat race will subdue. It’s up to those with the purchasing power to decide that a price is too high to pay.

And for the rest of us not caught up in the frenzy, we still benefit from and take part in that interaction that drives the industry. Whether we like the prices of some pieces or not, or just outright can’t afford the upper echelon, we still have the power to choose. Before buying the next watch, and the next, we all have a responsibility, I think, to do right by ourselves, and get back to basics. For the sake of the industry, for the sake of our sanity, it’s time for us to find the best watch… for ourselves.

Be your best. Buy your best.

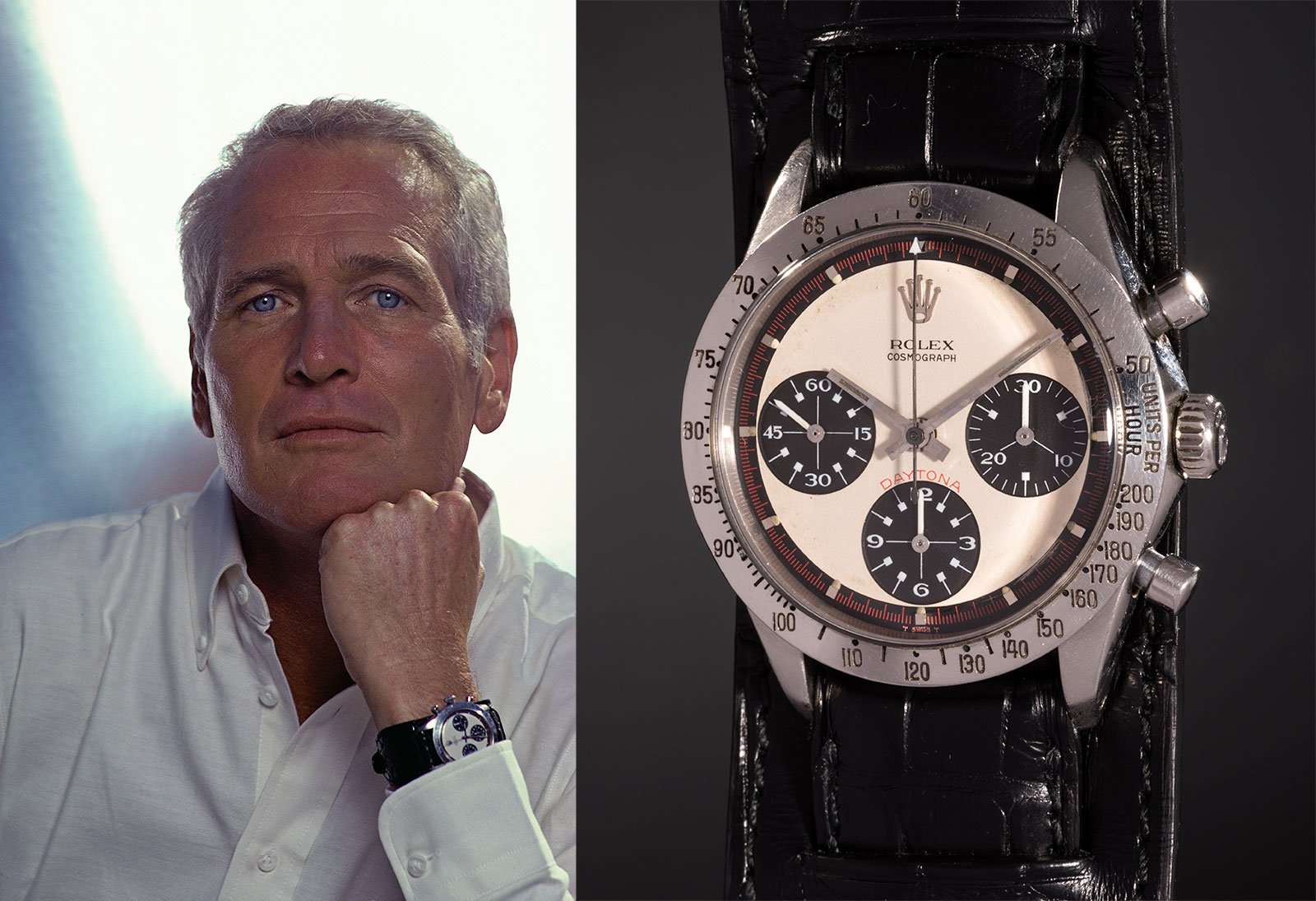

Andy Warhol, Paul Newman, Buzz Aldrin, Jacques Cousteau; if watches and these names mean anything to you, you already know and see their famously corresponding watches in your mind. Prominent individuals of history did not seek out the famous watches of others to achieve their status. They wore watches, they did what they did, and the world remembers them (and their watches). They were themselves completely, following their dreams.

…whether you’re known across the globe or across town is just a matter of scale.

Like owning luxury watches, I expect relatively few people of any era to achieve historic status. But whether you’re known across the globe or across town is just a matter of scale. If there is anything worth striving for that we can learn from others, it isn’t the status of possessions but rather actions of integrity. There are thousands of watches out there, to think any of them could elevate you is foolish. The Patek that the Dalai Lama made famous certainly won’t make you famous. It won’t buy you enlightenment either.

You’re your only hope.

There’s a watch out there for you, ready to accompany you on your life path. There’s no reason each and every model of watch out there can’t be famous, even as a home-town hero, even just among loved ones. I’d rather own a watch that works for me, in my life, than one that worked better for someone else. I’d rather people that know me recognize and value the watches I wear because of their association with me than, say, Buzz Aldrin. Find the watches that work for you, don’t work for your watches. Buy the piece that can accompany you effortlessly and then go forth without a backward glance. And don’t worry about anyone else. When the trends burn out, when the bubble bursts, you and yours will still be going strong, making your own prestige.

And I’ll continue to read, to learn, to write, and to dream. I’ll keep visiting the museums I love. I have no problem with trying on the defining pieces of haute (or hot) horology, if only just for fun. Watches are still art, and art is to be enjoyed. I haven’t given up hope. Besides, as Gerhard Richter says, “Art is the highest form of hope.”