The Casio Collection Of Nuno Gomes — Setting World Diving Records With A Casio G-Shock On The Wrist

The world’s watery depths are some of the most remote and hazardous places to explore. Deep-cave diving, then, is perhaps an extreme sport within an extreme sport. Fratello speaks to one man who has set world records for diving in these forbidding places and who relies on Casio watches for life-risking work underwater. He has taken G-Shocks rated at 200 meters to over 300 meters deep. Like deep-sea diving, deep-cave diving requires focus, technical ability, mental resolve, and experience. Aside from the risk of getting lost or equipment failing due to immense pressures, breathing deep-dive gas mixtures at extreme underwater pressures — usually, a combination of helium, nitrogen, and oxygen called Trimix — can kill you in multiple ways. At extreme depths, helium can send you into deadly fits. Oxygen can also become toxic.

Nitrogen acts like a narcotic, so the deeper you go, the harder it is to function. Divers compare narcosis to drinking alcohol on an empty stomach. At more than 200 meters down, the effect is similar to having downed four or five cocktails simultaneously. As you descend, if you don’t breathe properly, carbon dioxide can build up in your lungs, which could make you lose consciousness. If you ascend too fast, the nitrogen and helium that’s been building up inside your body under the enormous pressures can turn into minute bubbles, leading to what divers call “the bends.” It can result in severe paralysis, pain, and even death. To avoid getting the bends, ultra-deep divers spend many hours on the ascent, sitting at a specifically targeted depth for calculated periods to allow for decompression, letting the gasses safely leave their bodies.

The ultra-deep cave diver

And that’s just the gasses. In ultra-deep cave diving, it’s also possible to become trapped and disorientated, particularly if sediment gets swept up near the cave floor. Worse still, you can get stuck in the mud, the thick substance sucking you in like quicksand. Even with a helmet fitted with powerful lights, visibility can be close to nil. Throw in the disorientating effects of nitrogen narcosis, and it can quickly turn deadly for even some of the world’s best divers.

Nuno Gomes is a renowned deep diver who, in 1996, set the Guinness World Record for the deepest cave dive. It happened in the South African Boesmansgat cave at a depth of 282.6 meters (927 feet). The cave sits at an altitude of 1,550 meters (5,000 feet) above sea level, which resulted in Gomes having to decompress for an equivalent sea-level dive of 339 meters (1,112 feet) to prevent the bends. You can watch a video of that world-record-setting dive here.

An Atlantic upbringing

Gomes was born in Lisbon. Growing up on the Portuguese coast, Gomes says he pretty much lived in the sea, learning to spearfish and swim in the rough seas that Portugal’s Atlantic coast is famous for. When Nuno was 14, he and his family moved to South Africa and settled in Pretoria. Despite being a landlocked city, it is home to some of the world’s deepest water-filled caves. Thus, Gomes says, “I guess that my deep-cave diving, over time, was just a natural progression of going deeper every time in the sea and in the caves.”

Though Gomes is now a world-renowned diver, some of his first experiences in those depths did not go so well. “My first-ever dive, which took place while I was still busy with pool training, was a solo salvage dive done in 30 meters or 100 feet of water in nil visibility. I had a rope tender who asked if I wanted a swig of brandy to warm me up before I went down; I declined. The dive was successful, and I managed to recover the outboard motor, even though the dive tender paid out far too much rope and I became tangled up in it. After that, diving was ‘easy’,” Gomes explains.

The beginnings of deeper dives

“That dive was followed by my first official ‘open-water’ air dive after completing the actual pool training. It was in a cave to a depth of 55 meters or 180 feet,” Gomes tells Fratello. “The dive went off without incident; it was a great dive, and I knew that both deep and cave diving were the types of diving that I wanted to do forever. After doing many air dives to 90–100 meters or 300–330 feet, I realized that it would be wiser to use Trimix (an oxygen/nitrogen/helium gas blend) for deeper dives, and I switched to using the Mixed Gas tables in the US Navy Diving Manual. So the natural progression started, going deeper every time both in the sea and in the caves,” he explains.

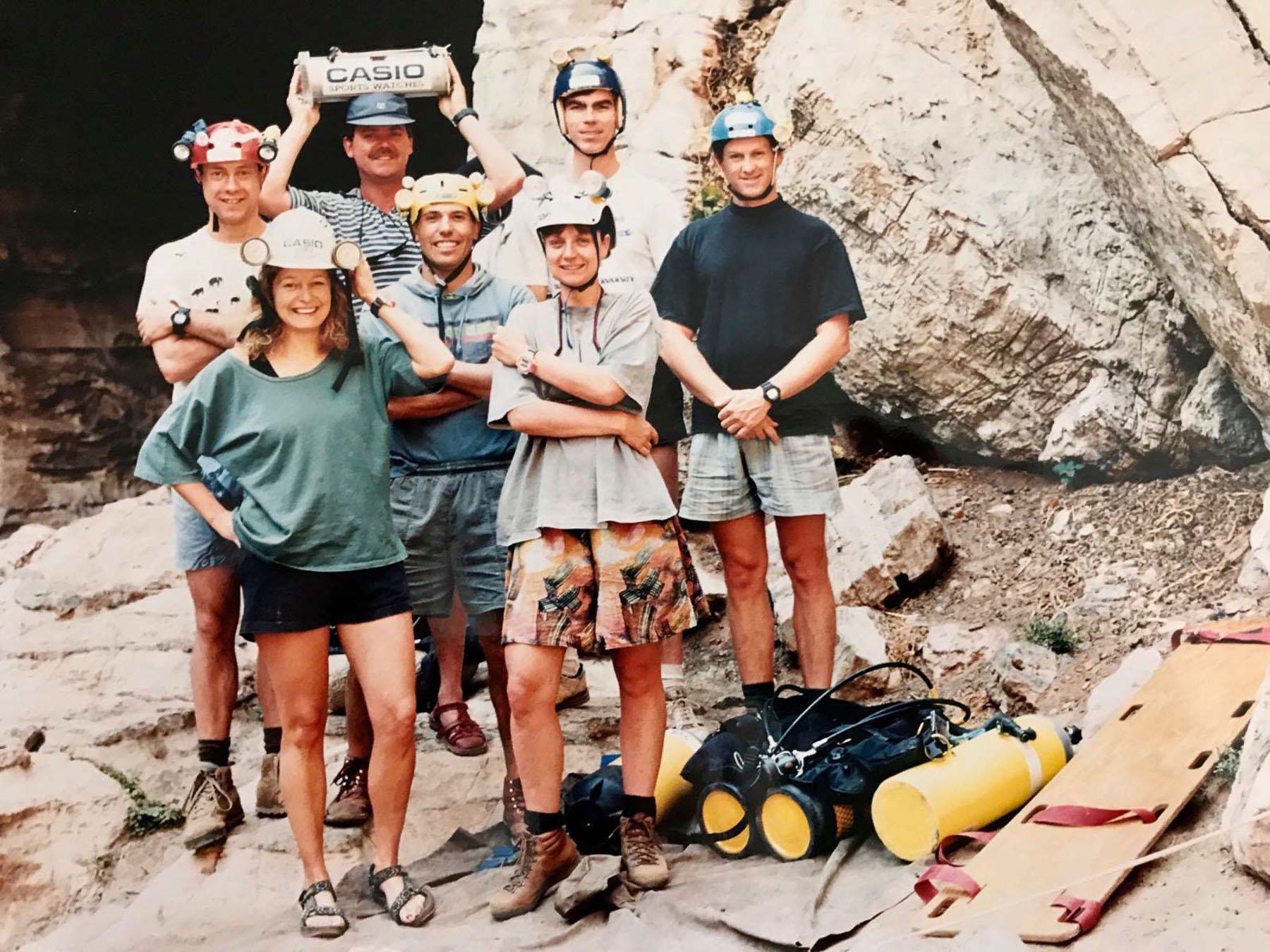

Ultra-deep cave diving was a natural progression as Gomes joined and pioneered many expeditions. He dived in all the known water-filled caves in Southern Africa. Then, on the 23rd of August 1996, Gomes set out on his most ambitious dive to date.

Image: Reefdivers.co.za

The South African cave

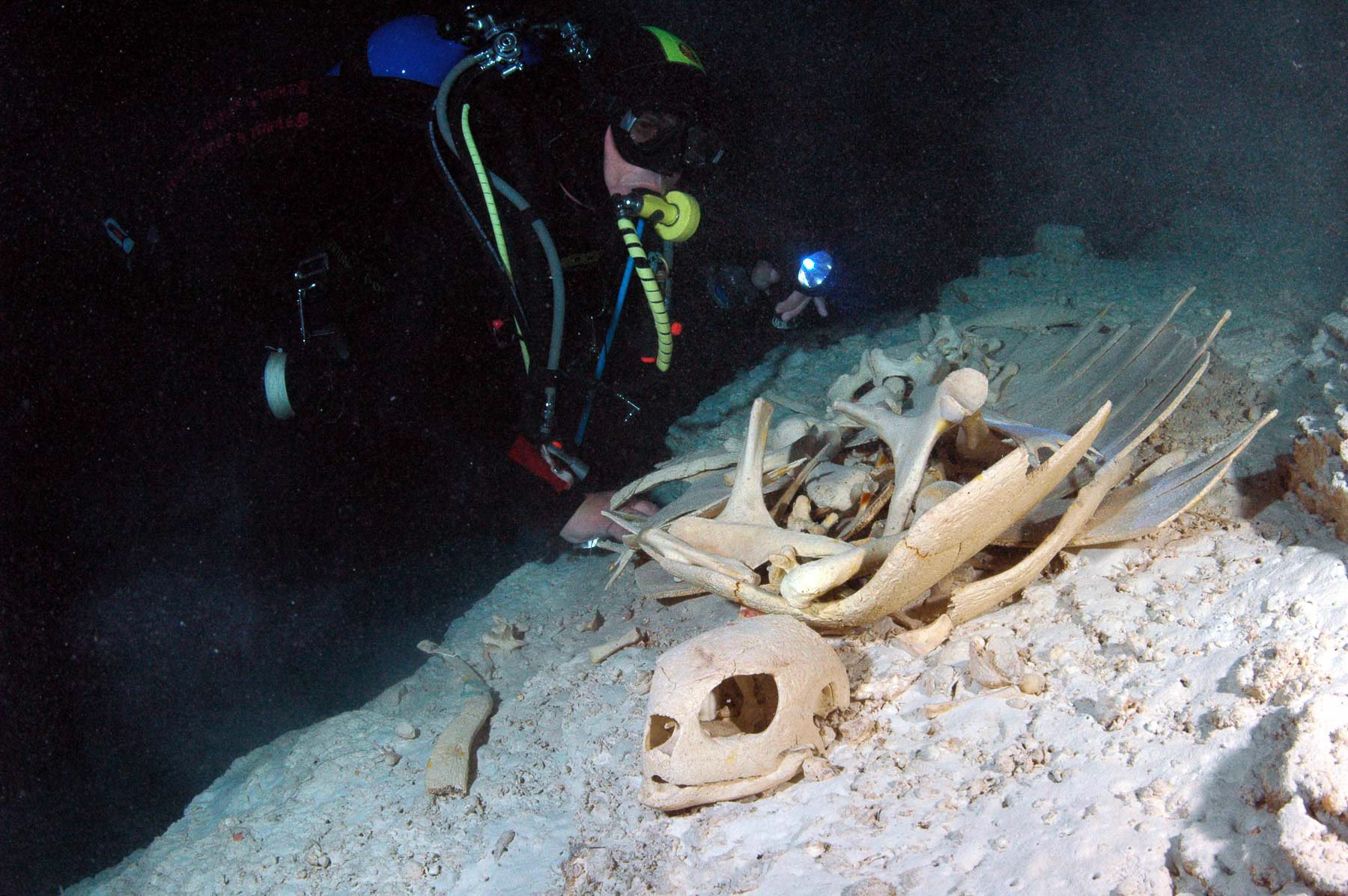

Boesmansgat, also known as “Bushman’s Hole,” is a forbidding place. Located on a privately owned farm and set amid thousands of acres of rolling landscape dotted with grass and termite mounds, there’s a crater dozens of meters wide from rim to rim. At the center of the crater is a relatively small basin of water, no bigger than a small swimming pool. This is the entrance to Boesmansgat, and no one knew how deep it was until Gomes touched the bottom in 1996.

Gomes had already dived there before, reaching more than 75 meters on his first visit in 1981. He’d dropped through a narrow vent-like structure at the entrance to a vast underwater chamber at around 50 meters. In 1993, Gomes was part of a team that helped deep diver Sheck Exley get to the bottom of the cave’s sloping floor, reaching a depth of 263 meters or 863 feet. But the cave has claimed the lives of experienced divers, including South African Deon Dreyer in 1994 and Australian Dave Shaw, who perished while trying to recover Dreyer’s body in 2005. It almost took the life of Gomes too.

A close call at the world’s depths

As told in the book The Darkness Beckons, when setting his record in 1996, Gomes almost got stuck in silt on the cave’s floor.

“Suddenly and unexpectedly, the bottom came into sight, with only two of my torches still working (the two SabreLite beams lit up the bottom clearly; the pressure had squashed the other two torch bodies, and the terminals were not making contact) my view of the bottom and moment of glory was short and sweet. I saw a lunar-type landscape of gray silt with the odd small rock sticking out, and there was some slack rope on the flat bottom.

There were holes in the gray silt where the weights had gone in and a small ledge which I had to get past to reach the deepest spot about five meters away horizontally. There was only one way: I had to swim whilst taking up the slack on the rope. Since I was negatively buoyant and had no time to inflate the wings (buoyancy aids) I landed on all fours.”

A nightmare come true

Gomes got stuck in the mud at the bottom of Bushman’s Hole for two minutes before escaping.

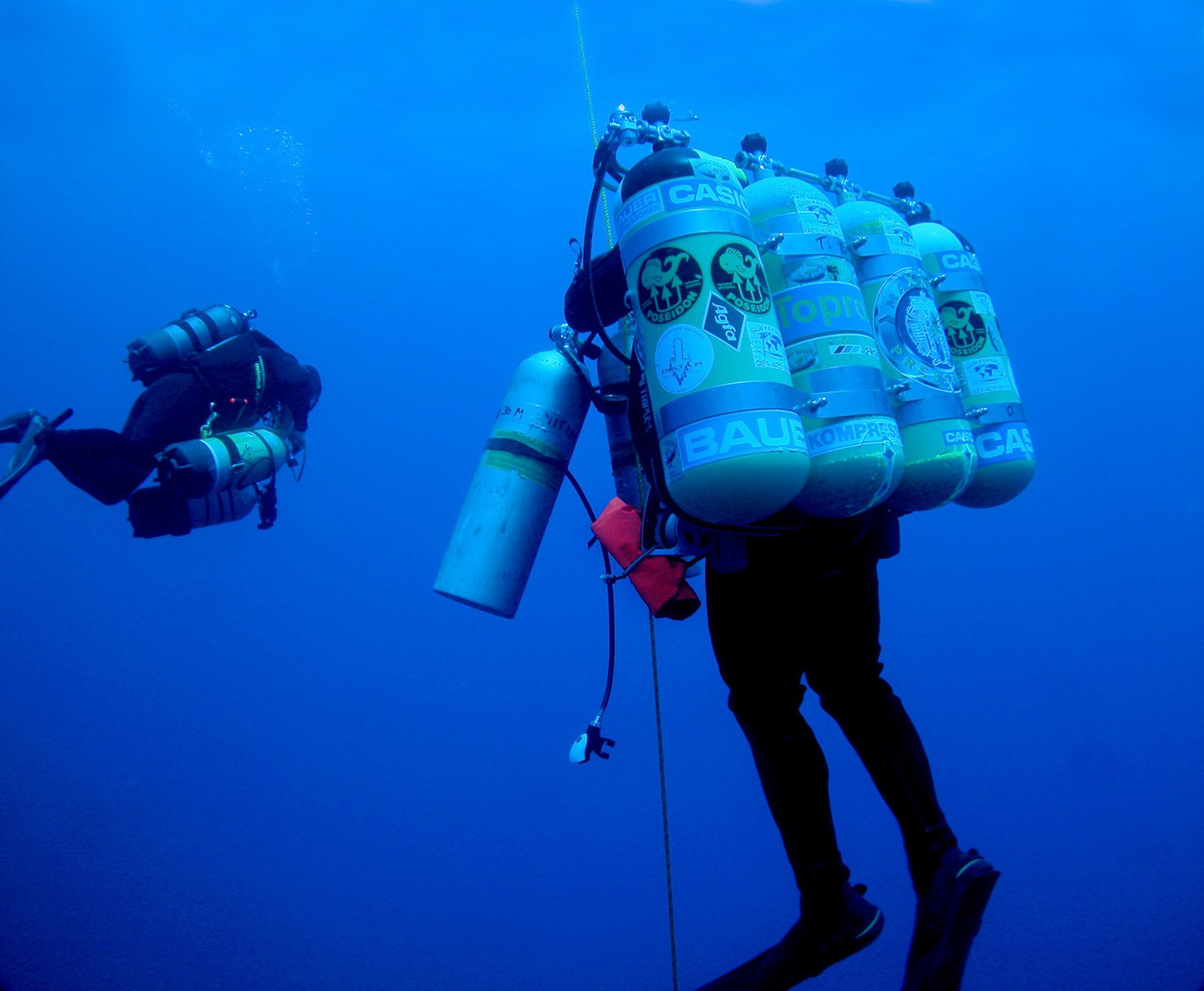

“My worst nightmare came true: a silt-out at the bottom of a very deep cave with a slack guideline while on all fours and under the influence of nitrogen narcosis and helium tremors. My priority was to stand up without losing balance, becoming tangled in the line, or losing it. The quads and two side-mounts did not help. I tried to swim up but failed and became dizzy. I relaxed and inflated the wings; it took 30 kg of lift to ascend 15 meters and get out of the mud and silt.”

A 15-minute dive to the depth then required a grueling 12 hours of decompression to safely ascend, including five hours at just three meters below the surface, battling the cold and exhaustion.

Casio collector and world-record setter

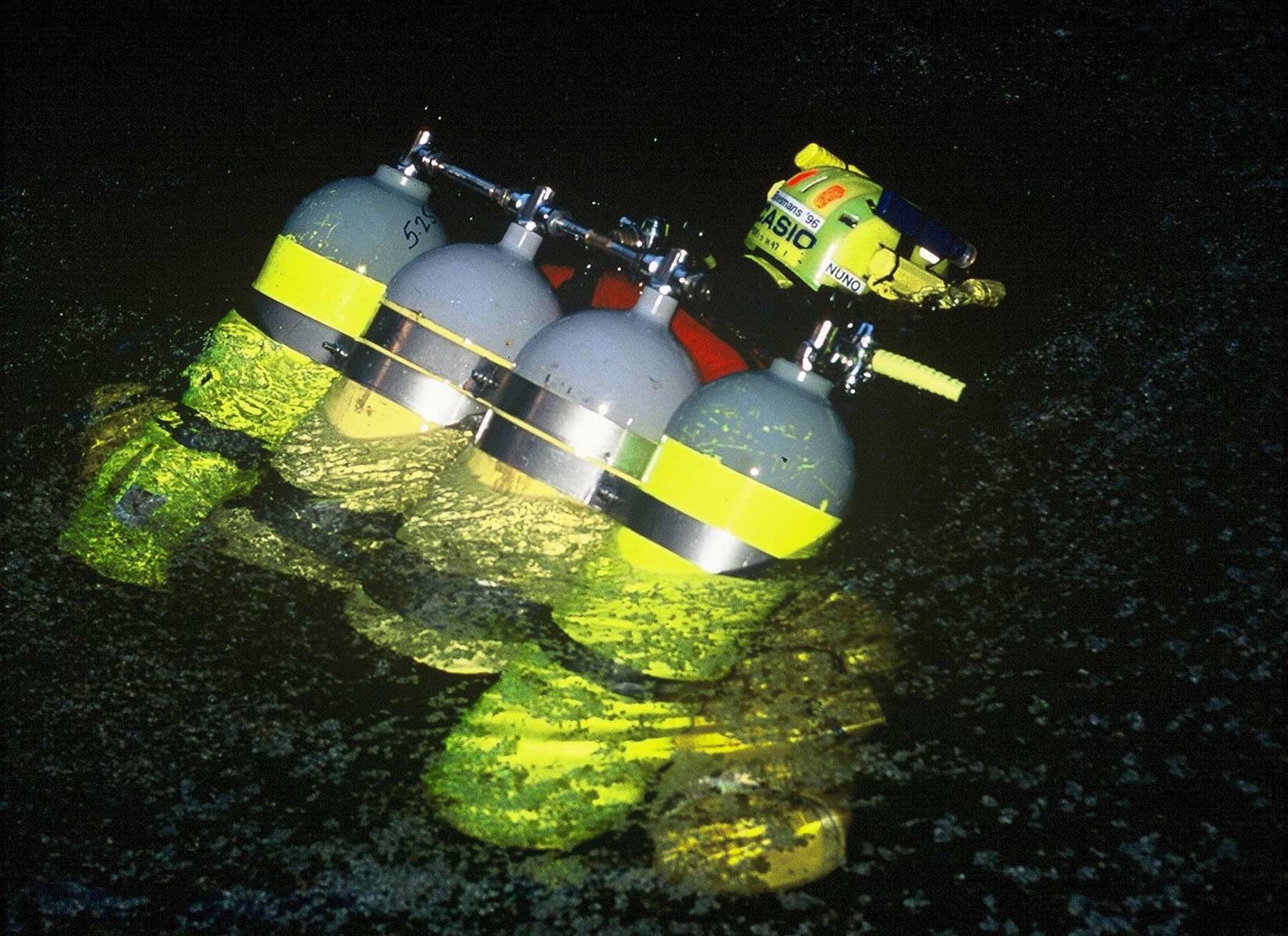

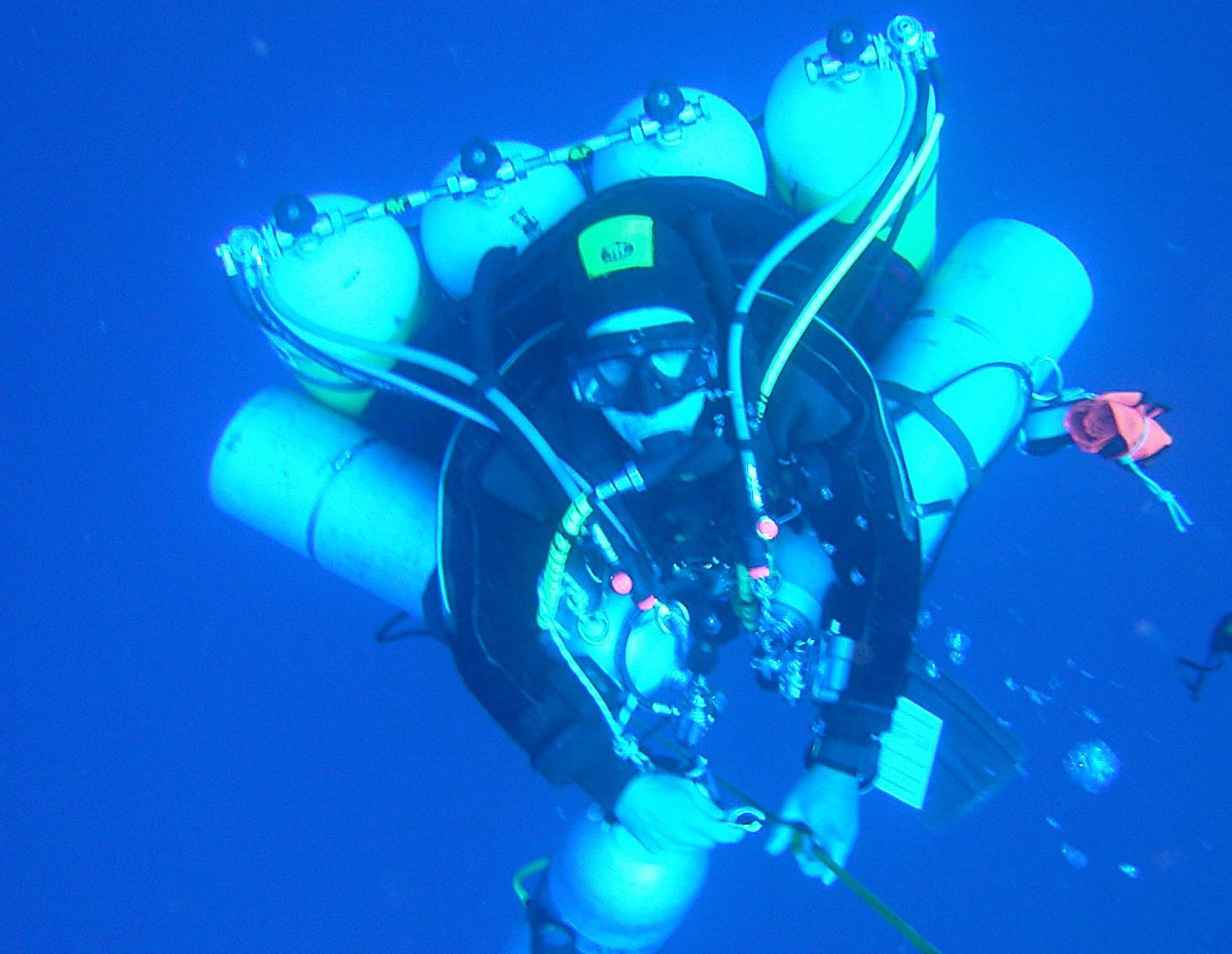

Leafing through photos of Gomes’s incredible feat at Boesmansgat, you can’t help but notice his Casio watch on his wrist. Clearly, it is being used to help time his decompression intervals. Gomes has an interest in Casio watches, and the brand has been a sponsor of some of his world-record-setting feats. “Divers, including me, like watches, even if they use dive computers,” Gomes says. “For some, it is like a status symbol that they can use every day when not diving. Even though I have a lot of dive computers, I use a dive watch, especially for the deeper dives.”

In early photos of Gomes and his support team, you can see the entire group sporting a Casio of one description or another, including G-Shocks and what look to be Casio F-91Ws. Unlike many of us, Gomes has tested his watches in literally life-threatening situations and pushed them to depths and extremes far beyond their advertised capability. Gomes has a small collection of Casio watches, which he has taken on multiple dives, including his world-record-setting ones.

A Casio failsafe

Gomes says he collects Casios because of their durability and the affinity he has with the brand after taking them on so many dives. “It is my experience that, at least, Casio watches can go way deeper than their listed working depth. I have personally pressure-tested many dive computers and Casio dive watches. While dive computers have often failed when approaching 250–280 meters or 820–920 feet, I have never yet had a Casio G-Shock fail on me. The Casio G-Shock is only rated at 200 meters or 660 feet, but I have tested it to 350 meters or 1,150 feet several times, and it has passed with flying colors,” Gomes tells Fratello.

Gomes uses a combination of a dive computer, a watch, and a printed decompression schedule to create multiple fail-safes on his deep dives. “For ultra-deep dives, one would most likely not rely on dive computers for decompression purposes. Also, in case both dive computers fail at depth (and this has happened to me), one can easily use the dive watch with a printout of the decompression schedule to successfully decompress on the depth-marked ascent/decompression line,” he says. This means that the Casio G-Shocks have saved Gomes from risking the bends by losing the ability to keep track of his decompression schedule.

A deep-diver’s philosophy

How does Gomes come to terms with these personal risks? Gomes quotes Exley, who was a friend, in explaining his philosophy. “The late Sheck Exley, from whom I learned a lot, also always said that these dives were not necessarily dangerous, but they were hazardous. Dangerous dives mostly occur when one does not take the necessary precautions or exceeds one’s natural abilities. I don’t specifically need any type of motivation if I want to do a dive and feel I can do it I do it; I enjoy challenging myself. I don’t ever try to go deeper than someone else; I try to improve on my previous records if I think that it is possible. However, even with that said, the very deep dives take a lot of preparation, time, and resources.”

The reason for the multiple fail-safes is very real. Indeed, Gomes has experienced the extreme pressure of deep dives crushing his dive computers before. “I like to use the simplest type of equipment and also to safely minimize the amount of equipment used. It is critical to test and be able to service your equipment if at all possible. All the equipment that I use is readily available off the shelf, even decompression software. Some of the equipment can fail at depth because it is being pushed well beyond its guaranteed working depth. It is possible to pressure test some of the equipment, but it can still fail under actual conditions. Progressively testing the equipment under actual conditions is possibly the safest way,” he tells Fratello.

Final thoughts

After setting the record for the world’s deepest cave dive, Gomes also earned a Guinness World Record for the deepest sea dive. Along with his team, he achieved a depth of 321.81 meters (1,056 feet), in the Red Sea in June 2005. In tense moments during this video, Gomes comes close to running out of oxygen on his ascent back to the surface. It is both exhilarating and, at times, harrowing to watch, and it highlights the hazards in the sport even with exhaustive preparation.

At the end of our discussion, I had one burning question: why does Gomes keep doing it? “Pushing the limits is quite interesting. It is human nature to find out what the limits of human endurance are,” he says. If you’d be interested in knowing more about these dives and experiences, Gomes is also an author.

Thanks for reading, dear Fratelli, and thanks to Devin for his advice on this story. Let me know if you have questions for Gomes in the comments and I will pass them on.