Can The One Who Invented The “Roman IIII” Numeral Please Stand Up?

I remember my dad walking around the house, winding the antique clocks on the walls when I was a kid. I think practically all of them had Roman numerals marking the hours. At that time, I never noticed what kind of “four” they used. I didn’t bother checking whether it was a subtractive “IV” or an additive “IIII” — the latter of which is also known as the “watchmaker’s four”. But since I often wear my Cartier Santos Galbée XL, I started wondering where the “IIII” actually came from. So, I decided to look it up on the big interwebs.

Now, please don’t expect any final answer on the origins of the “watchmaker’s four” at the end of this article. What I found is that there are many stories about where the “IIII” on watch dials comes from. None of them, however, have been confirmed by anyone. It’s probably a combination of all those stories together. But at least I can now give some kind of explanation to people who ask me about it and, most importantly, to my father, who still winds the clocks at my parents’ house. Especially the one in the entrance hall, which also chimes proudly every quarter of an hour. Anyone visiting my parent’s place for the first time always bounces up a little when that clock chimes.

My own Cartier Santos Galbée XL, on which the IIII is interrupted by the date window

Of course, that clock could also run without the chiming, but my father really likes it. Besides, although he’s certainly not a professional watchmaker, he does perform some maintenance on his clocks from time to time. I remember him repainting the Roman numerals on one of them. I think the chiming makes him feel proud of the work he’s done to his clocks. But enough about my father. Let’s get back to those explanations on the origins of the “watchmaker’s four”. I’ll present them in order of plausibility, from the least to the most plausible.

- Nomos uses both the “IIII”…

- …and the “IV” notation

The “IV” notation was seen as a sign of bad luck

The first category of explanations has to do something with the fact that the use of the “IV” notation was seen as bad luck. In Roman mythology, Jupiter (written as “IVPITER” in Latin) was the god of the sky and thunder. The Roman parallel to Zeus in Greek mythology, “IVpiter” was also the king of the gods. Apparently, using the first two letters of his name could potentially hurt his feelings. To avoid his anger leading to terrible storms or long periods of drought, people started using the “IIII” notation instead. Not convinced? Well then, I have another one about Charles V.

Charles V lived in the early 1500s, and — fun fact for me as a Dutchman — among other titles, he was Lord of the Netherlands from 1506 to 1555. Some say he believed the “IV” notation to bring him bad luck as it subtracted one from his own title. Therefore, he made people use the “IIII” notation instead. Still not convinced? Here’s another one about Louis XIV.

Patek Philippe seems to prefer the “IV” notation. Image courtesy of Oracleoftime.com.

Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King or Louis the Great — always nice to tell you something about my family tree! — lived between 1638 and 1715. With names like that, you can see that he thought quite highly of himself. But an actually impressive fact is that his reign — 72 years and 110 days — is the longest of any monarch of a sovereign country in history! Well, apparently, King Louis XIV also thought it would be better if people used the “IIII” notation, just to avoid them using part of his title on clock dials.

You’re still not convinced, are you? Me neither…

Better suited for the poorly educated

All these stories seem to have entered the urban-myth mill at some point. I think it probably took a little more to upset the Roman king of the gods than just using the first two letters of his name. And the “IIII” notation had appeared long before the two monarchs above were even born. So, on to the next possible explanation for the “watchmaker’s four” — accessibility.

H. Moser & Cie always does things differently!

Consider this: nowadays, many of us are quite well educated, or at least we know how to read and do some simple math. But in the early days, not that many people knew how to read, let alone add and subtract. So, to make it easier for most people to read the time, people chose to use the additive notation “IIII” instead of the subtractive notation “IV”. This, of course, makes sense. But — and this is a big BUT — then you should also use the “VIIII” notation at nine. And that doesn’t happen. Like, ever. So, I kind of feel like this argument doesn’t make a lot of sense either. Let’s get to the last couple of explanations, which, together, I think do make a lot of sense.

The “IIII” was there first

I found this explanation on the Foundation of High Horology’s (FHH) website. It states that the additive principle was actually the original principle. So that means the “IIII” notation was there already before the subtractive notation “IV”, which first appeared during the Imperial period. The Foundation also states that the subtractive principle was almost never used for official inscriptions, monuments, or sundials. So, when the first non-sundial clocks were made in the 15th century, they chose to go for the more common additive notation. That, however, doesn’t explain why watch brands nowadays are sticking to it.

The “IIII” creates balance on the dial

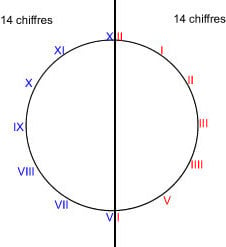

Well, the FHH has got us covered there as well with a few interesting insights. They all have to do with the visual characteristics of the “IIII” notation. First of all, it’s said that it balances well with the “VIII” on the other side of the dial — better than the “IV” notation, at least. Secondly, when using the “IIII” notation, you create four groups of four similar numerals, namely:

- I, II, III, IIII

- V, VI, VII, VIII

- IX, X, XI, XII

These groups, again, make the dial look better balanced as opposed to when you’d use the “IV” variant. The final visual argument for using the “IIII” requires some counting. Here are your instructions: divide the dial vertically into two pieces and count all the individual characters. You’ll see that there are exactly 14 characters on both the left and the right sides of the dial. Cool, right? I guess this helps balance out the dial again, but other than that, I feel it’s quite a far-fetched argument for using the “IIII” notation.

Final thoughts on the “watchmaker’s four”

So, as said at the start of the article, this leaves us with no definitive answer as to why there’s a “IIII” and not a “IV” on many watch dials. But I strongly feel that the combination of its more common usage and its visual characteristics make for a pretty strong case for the “watchmaker’s four”. Don’t you think?

Please let me know in the comments where you stand on this matter. And if you have any additional information or arguments, please share them with us!

You can also find and follow me on Instagram @fliptheparrot