Wrist Game Or Crying Shame: IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Ref. 3750

If I were to ask what IWC’s worst model line is, how many of you would say, “the Da Vinci”? While perhaps not everyone would share that opinion, I’ve always found it unfortunate how many people think so. Granted, I like IWC’s pilot’s watches and the Portugieser just as much as the next enthusiast. I also understand that stylistically speaking, many find them much more recognizable and “iconic” than the Da Vinci. But in my time collecting watches (over 15 years now), I’ve seen so many decry the Da Vinci based on looks alone. Perhaps understanding the significance of the watch in IWC’s modern history would help abate that sentiment somewhat. Then again, maybe we just like what we like, and no amount of explanation can undermine that. Let’s find out in this installment of Wrist Game Or Crying Shame.

Today, I’d like to share the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar ref. 3750. This is a neo-vintage classic in solid 18K yellow gold that you can pick up for less than €10,000. Maybe RJ’s penchant for gold is rubbing off on me, but this is a segment that I’ve been exploring quite a bit recently. There are indeed some great gold watches out there that come in under the psychologically satisfying €10K mark. In all honesty, though, I’m still quite surprised that an IWC perpetual calendar is one of them. While today’s example has an asking price of €9,900, it’s not uncommon to see this watch sell for €1,000 less. These photos are rather nice, though, so without further ado, let’s see what we have here…

The Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar is a stunningly significant watch

While many watch enthusiasts are familiar with the general history of the Rolex Submariner or Omega Speedmaster, far fewer, I believe, can say the same about the IWC Da Vinci. Admittedly, I was quite ignorant of it as well until just this past year. Having found the styling and price of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar attractive for years, I finally decided to dig a little deeper and found a fascinating story.

A brief historical background

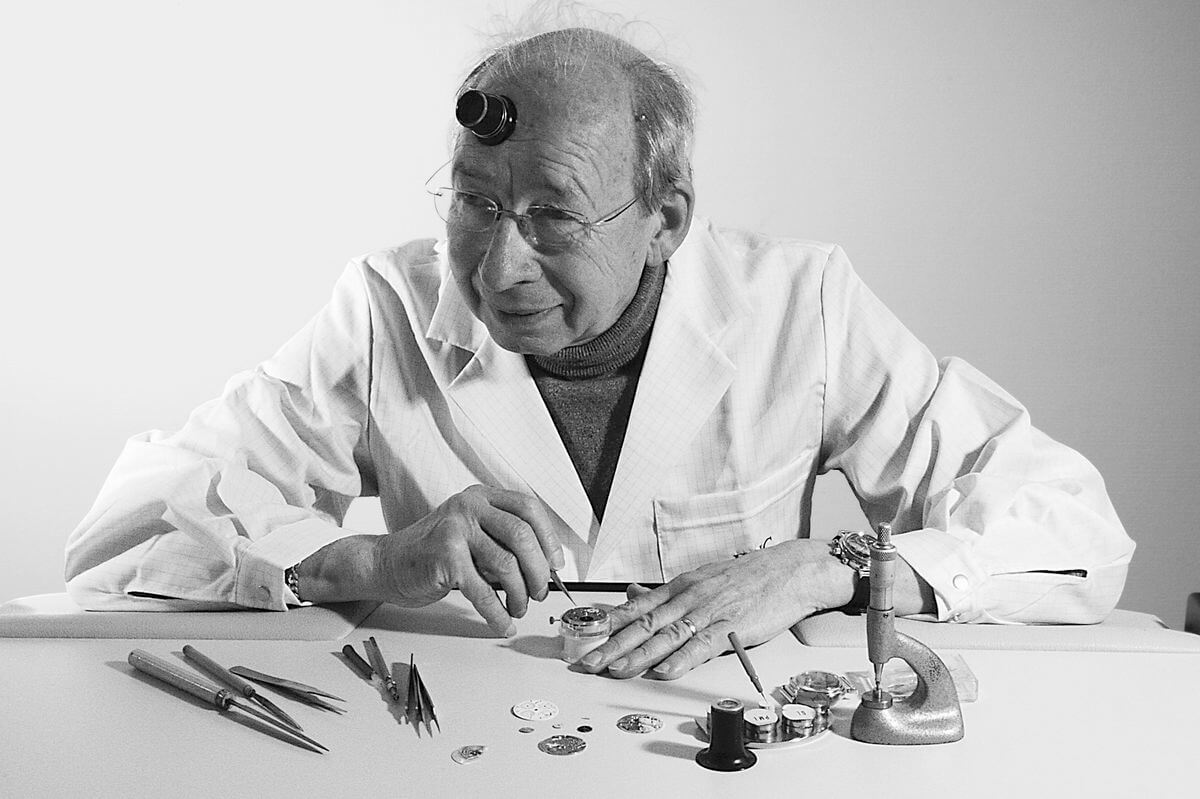

Kurt Klaus, now a veritable living legend in IWC’s history, joined the Schaffhausen watchmaker in 1957. Fresh out of watchmaking school, he began his work there by assembling movements. Eventually, though, Klaus caught the favor of the company’s technical director, head of production, and movement mastermind Albert Pellaton. In this wonderful interview, Klaus recounts, “From him, I learned the engineering of watch movements. I never have been in engineer school. I came direct from watchmaking school. But Albert Pellaton transformed to an engineer.” When Pellaton retired in 1966, he left quite a legacy of mechanical innovations, including the Pellaton winding system, which I highlighted here. But perhaps the greatest indicator of Pellaton’s impact on IWC was his mentorship of Kurt Klaus, who would usher IWC into a new era of complicated watchmaking.

Amid the Quartz Crisis in the 1970s, Klaus developed the IWC pocket watch caliber 9721. This was the brand’s first movement to feature a triple calendar and moonphase module. Though such a mechanical timepiece did not make much sense business-wise at that time, IWC’s owner Hans Ernst Homberger had the desire to keep mechanical watchmaking alive, and eventually, the company’s management agreed to produce a 100-piece run of the ref. 5500 pocket watch as a test of the market. Seemingly against all odds, the piece sold out, and Klaus continued to produce various special-edition pocket watches in the following years. His creations included a pocket watch displaying the 12 phases of the zodiac and even one with a thermometer function. Around 1980, however, sales director Hannes Pantli informed Klaus that he must continue his endeavors…except with wristwatches.

The goal and development of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar

For Klaus, the next logical step was a wristwatch with a perpetual calendar. However, it couldn’t be one like anyone had made before. Many perpetual calendars of the time (and even today) require buttons or pushers set into the case to adjust the calendar functions. These make it complicated to set and far from convenient for the user, so Klaus dreamed of a system controlled fully through the crown. His goal was to make the most user-friendly perpetual calendar in the world, one that was also suited to serial production. This would offer an experience and functions that no quartz watch could at the time. In so doing, it would prove mechanical horology’s place in an ever-modernizing world.

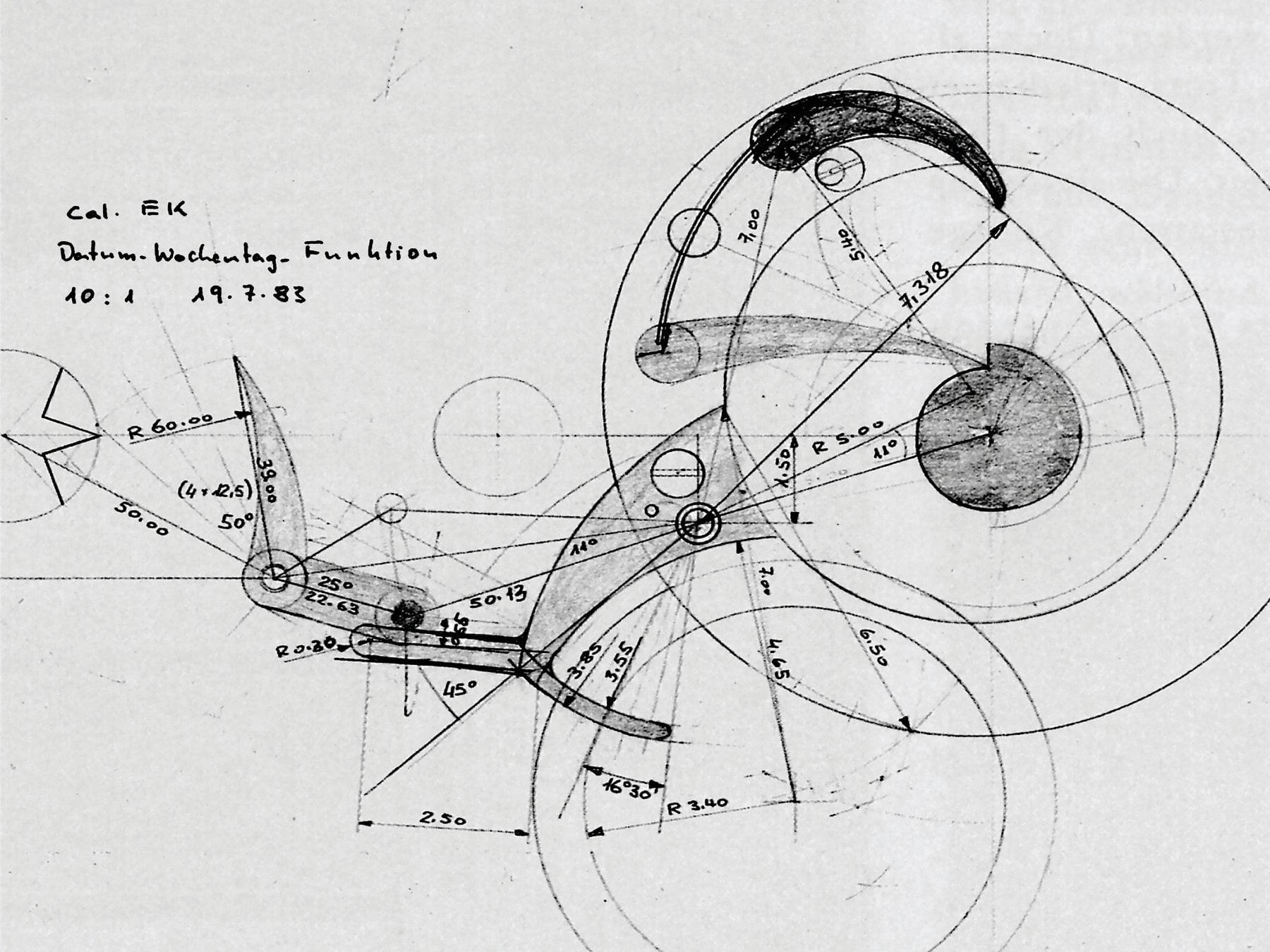

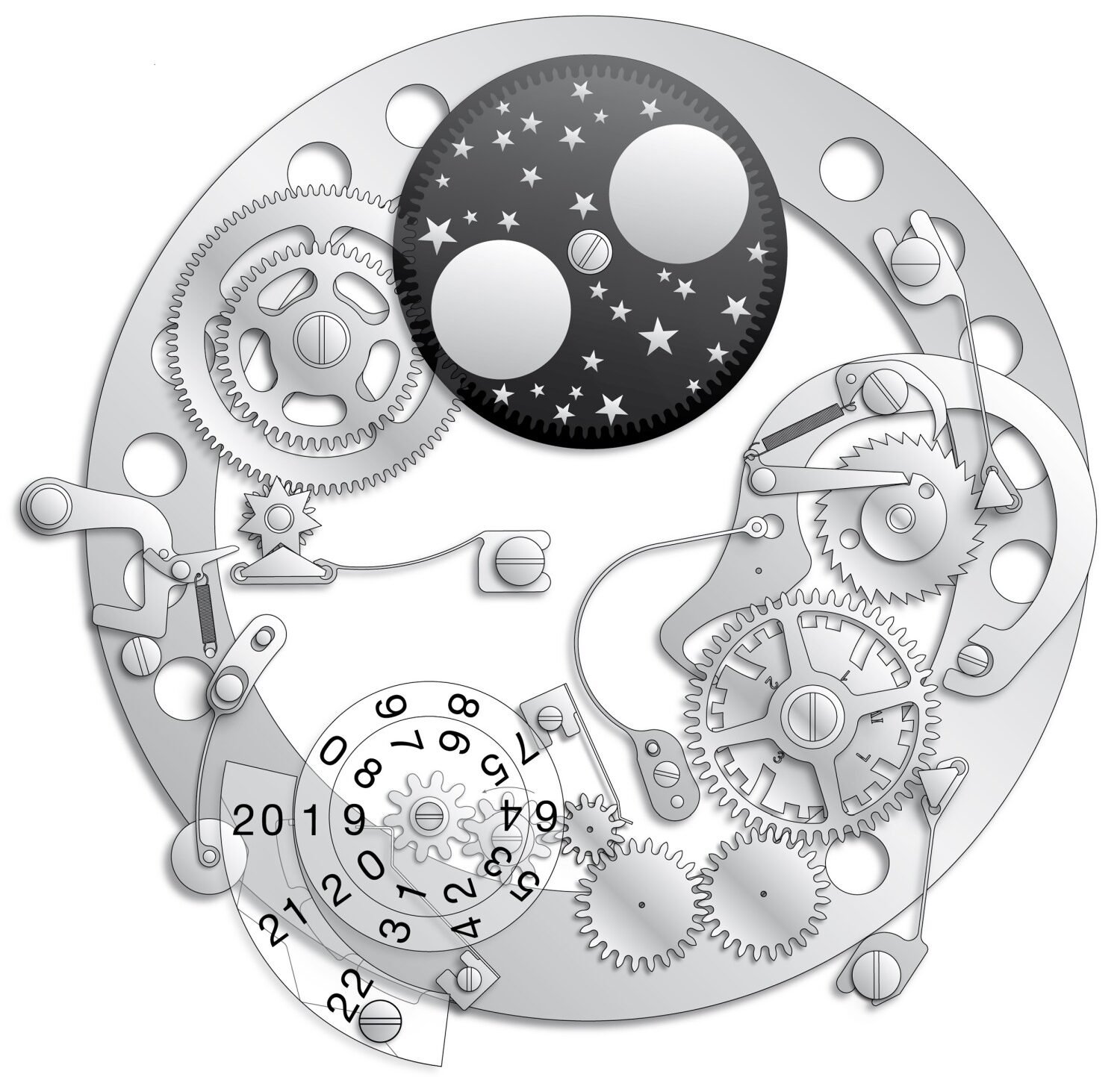

Klaus set to work conceptualizing a crown-set module for the perpetual calendar, which he would add to the Valjoux 7750 movement. The caliber’s integrated date function would provide the necessary power to advance not only the date but also the day, month, year, decade, century, millennium, and 122-year moonphase indicators. Klaus used a series of levers, toothed wheels, pawls, and cams to make this happen, with the month cam playing the biggest role. I will spare you all of the technical details today, mostly due to time and my admittedly limited understanding. If you’re interested, though, please read up on what each component does in this article on IWC’s website. The takeaway is that Klaus’s module, using only 81 components, revolutionized the operation of a perpetual calendar. Accurate until 2100 with no user intervention, it was also the first to display a four-digit year on the dial.

Design and reception

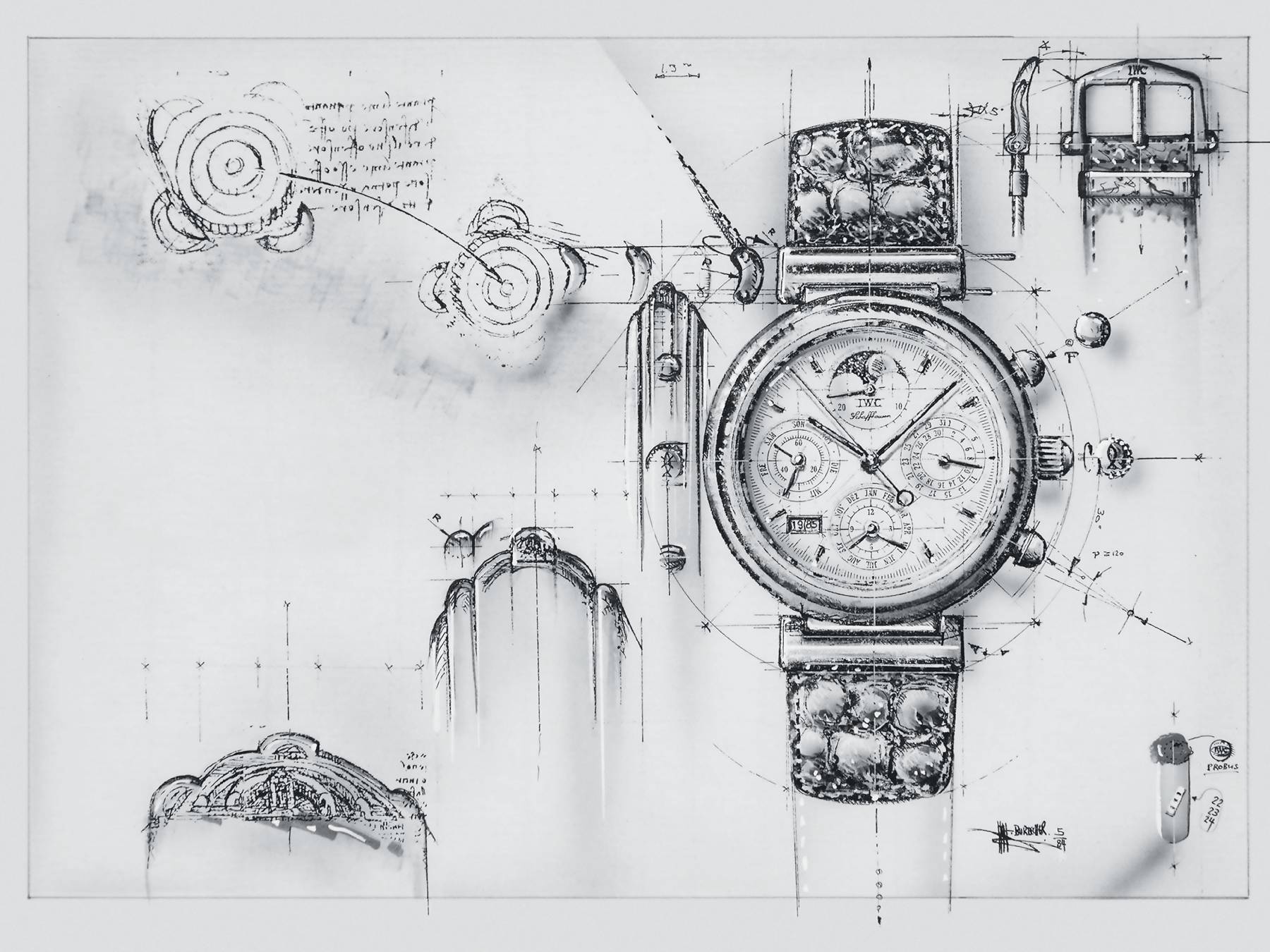

IWC decided that the watch that would house this innovation was to be called the Da Vinci. It would follow the brand’s forward-thinking Da Vinci Beta 21-powered model from 1969. While that model had a futuristic hexagonal shape and a cutting-edge quartz movement, the new Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar would be a marriage of classicism and progressive mechanical watchmaking. IWC’s designer Hanno Burtscher, himself an admirer of visionary Leonardo Da Vinci, drew inspiration for the watch case and dial from drawings in the great polymath’s book Codex Atlanticus. These drawings showed rounded harbor fortifications that Da Vinci had designed in the late 1400s. Burtscher adapted their shape to the round design of the case, crown, and pushers while using the “sectors” within the fortifications to guide the layout of the sub-dials.

In the mid-1980s, the 39mm double-tiered case with its domed crystal struck the desired balance between tradition and modernity. One of its most distinguishing characteristics was its swiveling lugs, which allowed the strap to fit well regardless of one’s wrist size. Burtscher penned the design in 1984, and by 1985, after nearly five years, Klaus also completed working prototypes of his caliber 79060. IWC presented the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar ref. 3750 at the watch fair in Basel on April 11th of that year. Industry figures took notice immediately, applauding Kurt Klaus’s complete reimagination of the perpetual calendar complication. With this, it seemed, mechanical watchmaking had a future. To the surprise of everyone at IWC, the fair resulted in over 100 orders for the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar. By November of 1985, IWC had made 500 examples, and the watch became a tremendous success.

If I may…

The historical context of this watch alone makes it fascinating for me. I adore how Kurt Klaus took it upon himself to carve out IWC’s future in complicated mechanical watchmaking with this model. Not to mention, I could listen to him recount the story of its development for days on end. However, I also appreciate the watch from an aesthetic viewpoint, so let me explain why. First, the dial layout is complicated, yes, but it remains magically legible. Notice how the date indicator at 3 o’clock features 31 full numbers that alternate on different levels. This maximizes the minimal space while not resorting to hard-to-read dots for some dates. Additionally, the sub-dial sectors and the mix of blue and gold hands effectively separate the chronograph and calendar indications. The long gold hands are for the calendar, while the short blue ones are for the chronograph. It’s simple but brilliant.

I also find the case design charmingly old-school and elegant. It measures 39mm wide, 46mm long, and a hair under 15mm thick due to the domed acrylic crystal. Those measurements are just about perfect for my wrist, and that’s even before considering the articulating lugs. This is one of my favorite features on a watch in general, and I truly wish that more cases had them. This look carried the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar through 2003, and even if it looks a bit dated now, I think it is legendary in its own right.

This example

The Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar pictured in this article is an early example from 1987 with German date and month indicators. This watch is available for €9,900 from the Austrian dealer Juwelier Bargello. It comes on a dark brown leather strap with a seemingly period-correct buckle, and according to the seller, it shows hardly any signs of wear at all. Furthermore, it comes complete with the original box and papers, which is fantastic for those who like a full set. For an 18K yellow gold perpetual calendar alone, I think the price of this watch is more than fair. But add the simplicity of operation and the great significance of this model, and it just may be one of the best deals out there.

But what do you think? Wrist game or crying shame?

I understand that not everyone shares my opinion. As I mentioned in the intro, many dismiss the Da Vinci line, possibly because of how it has evolved. RJ mentioned in this article how he dislikes the tonneau-shaped models that IWC introduced in the 2000s. While some see those as a throwback to the very first quartz Da Vinci, honestly, they weren’t my cup of tea either. Now, I do like the shape and style of the current Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar quite a bit. It is truly a modernized version of the 1985 trailblazer. That said, I can see how one could argue that the Da Vinci line has not shown the greatest stability through the years. It has housed complicated and simple movements, both mechanical and quartz, and for some, that inconsistency may be its downfall. Others may simply not find it as attractive as other IWC mainstays.

Let me know what you think of the IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar ref. 3750 for under €10K by voting below. And don’t forget to leave a comment explaining your reasoning too! I’m very interested to see the outcome of this one…

Wrist Game or Crying Shame: IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar ref. 3750