A Few Slightly Less Obvious, Loosely Cohesive Perspectives On Watch Design

Wristwatches have been mainstream for a little over a century now. This gives us a decent timeframe to reflect on watch design and its evolution. We tend to throw terms like “watch design” and “aesthetics” around loosely, but I feel that these concepts warrant a closer look and a slightly wider perspective. Consider this my attempt to step back and try to put them in a proper context. The aim is to help you sharpen your eye for evaluating watches, based on their aesthetics.

I will not be going through watch designs as they evolved through the decades. I have done that before in this earlier article. Instead, I want to try to clarify some of the concepts and sketch a broader context around these objects of our shared affection. I apologize up front if I become overly esoteric or take detours along the way. As I write this introduction, I realize that covering this subject in a single article is probably a bit overambitious. The topic may be too broad for a single piece. Still, let’s dive in and see where we land. Here are some loosely cohesive perspectives on watch design.

Defining “aesthetics”

Let’s start with the term “aesthetics,” which is often used when evaluating watches. Confusingly, the term has two overlapping yet different meanings. In popular use, it simply refers to how something looks. When describing a watch aesthetically, you tend to describe what you see in terms of shapes, colors, and materials.

The term traces its roots to the Greek aisthestai, which means “perceive”. This suggests a much broader meaning, reflected in the branch of philosophy concerned with the perception of beauty and artistic taste. You will find many definitions, but in this sense, the term “aesthetics” encompasses much more than mere looks.

An aesthetic experience is a state of consciousness focused on the beauty of a sensory experience. In this sense, you can have an aesthetic experience while gazing at a painting. However, you might also feel one while drinking your morning cup of coffee. When I describe the aesthetics of a watch, I refer to this broader experience of how the watch affects me through the entirety of the stimuli it serves up. Therefore, the aesthetics of a watch are quite different from its mere looks. This is a crucial nuance, as a watch design results in a fixed look on the surface level. However, its design, execution, and context determine its aesthetic. Describing a watch aesthetically, then, isn’t just a pretentious way of stating how it looks.

Watch design and aesthetics in a temporal context

From this perspective, while any single watch’s design does not change over time, its aesthetics can. Why? Because a watch — or anything for that matter — always relates to the current moment. It has its meaning within a temporal context. It affects people differently today than it did yesterday.

This is why the term “timeless” is much less applicable than you might think from its mere incidence in watch media. Something is timeless if it isn’t affected by the passage of time. We like to stamp all the classic watches as timeless because they have remained relevant. Cartier Tank? Timeless. Rolex Datejust? Timeless. Omega Speedmaster? Timeless.

Aesthetically, though, these watch designs have changed quite radically. A Cartier Tank has an entirely different aesthetic in today’s world than it did in the early 20th century. The set of sensory and associative influences it has on people has changed because the people and the context have changed. The watch isn’t timeless at all; it has merely remained relevant in a dynamic manner. Considering this, my undoubtedly unpopular opinion is that truly timeless watches are virtually non-existent.

Where are all the pre-1970 superstar watch designers?

Okay, I completely get it if you find the above just a bunch of semantic hair-splitting. Still, watchmaking is about precision and accuracy, so why not take the same scalpel to our thinking about watches? In any case, let me continue with a more down-to-earth question on watch design: where are all the pre-1970 superstar watch designers?

Today is often described as a time of appreciation for watch designers. We celebrate the designers of old and seem to have a taste for design-heavy new watches. Have you ever noticed, though, that we never speak of pre-1970 watch designers? Who were they? Where are the books and articles about them?

The answer is deceptively simple. Watches used to be made through heavily specialized and, therefore, fragmented processes, split over different companies. The effort was more technical than stylistic. As a result, a watch’s design was more likely to emerge from a collective effort than from a handful of brilliant pen strokes from a single exalted designer. This changed only when the watch world had to reinvent itself during the Quartz Crisis. Suddenly, the luxury watch became a work of art in need of an artist.

This is why watch design was largely unaffected by modernism

Perhaps the most impactful design movement of the 20th century was modernism. This movement was part of a broader cultural shift, world views, and philosophy. At its core, modernism looks for universal truth in minimalism and functionality, rejecting classical ornamentation.

While modernism virtually completely engulfed the fields of art and architecture, it left the watch world relatively unscathed. Modern art became abstract and conceptual. Architecture became devoid of decoration, reduced to basic shapes. One only has to look at any modern city to see the results — glass-and-concrete blocks everywhere.

Interestingly, you do not see this reflected in wristwatches to the same extent. Sure, Bauhaus-derived watches exist, but they never became the norm. You can argue that a Patek Calatrava or even a Rolex Submariner follows the modernist philosophy to a degree, but modernism hasn’t changed watch design nearly as much as it has art and architecture. Even when the design-first watch came along, the traditional focus on craft and artistry kept modernism at arm’s length.

What is next for watch design?

You see countermovements to modernism and minimalism emerging everywhere. Actually, that isn’t all that new, as postmodernism already started sawing the legs of modernism’s chair halfway through the 20th century. Still, many people feel design has lost the human perspective. You can only reduce something to its essential shape once, and the result can feel barren and cold. Postmodernism’s ironic and even alienating approach didn’t quench the thirst.

Some of today’s answers from the design, art, and architecture worlds include new ornamentation, computational ornamentation, and biomimicry. These efforts aim to revive the good things about the classical aesthetic without resorting to derivative and sentimental design. They lean on modern technology to introduce new shapes, embracing the complexity and detail of nature.

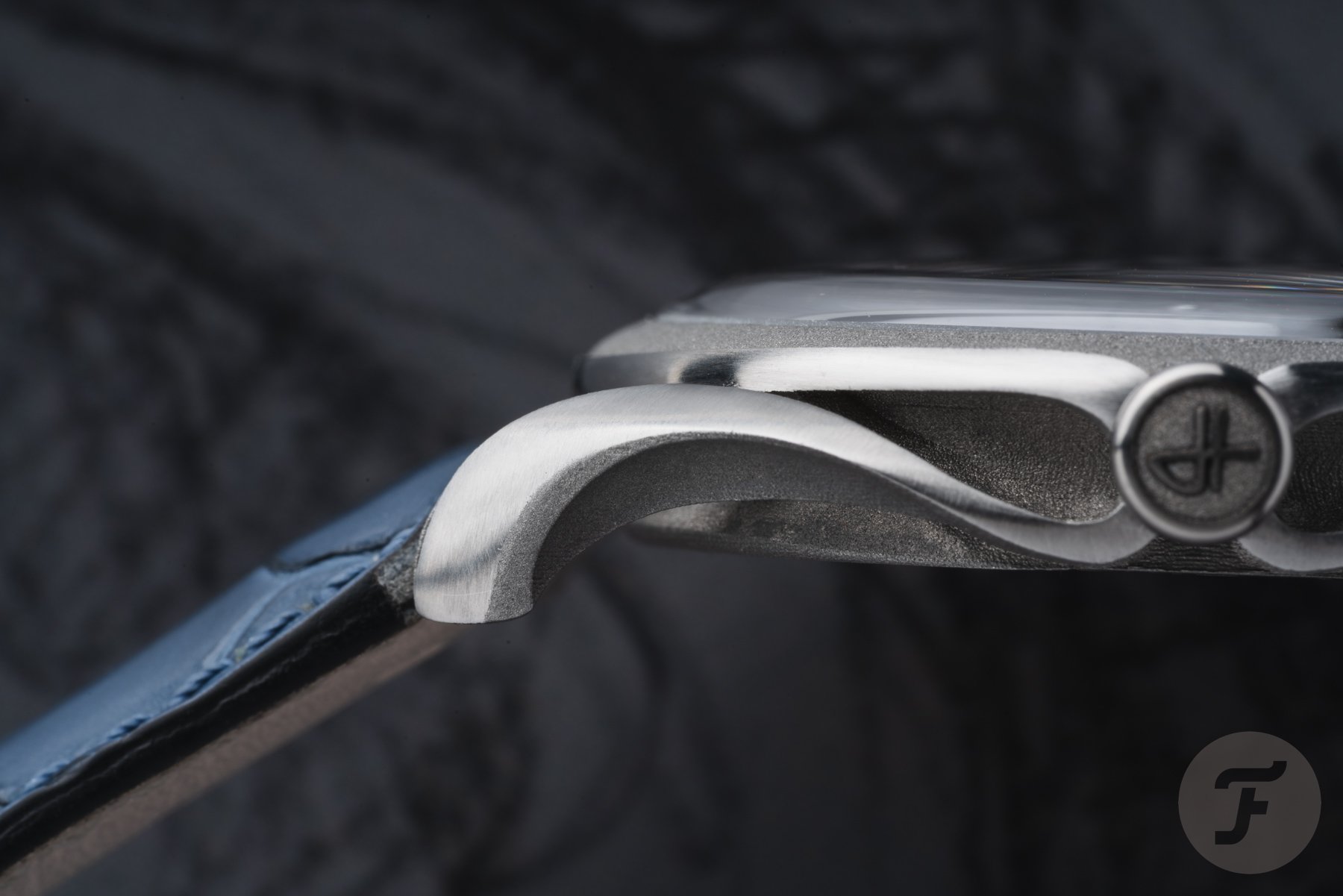

Since watch design didn’t go through a similarly all-encompassing modernist reset, it doesn’t require the same countermovements today. Consequently, the field stands somewhat disconnected from the leading aesthetics of our time. Still, one brand reflects the movement better than any other — Holthinrichs. Its Signature Ornament watch takes modern design and production techniques to create something distinctly new and organic. You see similar efforts from avant-garde brands in higher segments.

Closing thoughts

The big question is: do we want our watches to reflect the aesthetics of our time, or do we prefer the way they were before the era of the designer? The lasting success of 20th-century watch designs suggests the latter, although the more recent success of designs from the 1970s and beyond could open the door to something new.

There you have it — some loosely connected perspectives on watch design that, hopefully, provide an interesting bit of context. These are the types of ideas I like to apply to watches, and perhaps it explains some of my fascination with design. A design exists within a temporal and cultural context and, therefore, carries meaning and significance beyond the mere looks of an object.

I find this endlessly fascinating, and I hope I have been able to share some of that excitement here.