How Watches Work: What Is A Big Date Complication And Why Is It Useful? Examples From Lange, Zenith, Girard-Perregaux, And More

These days, watch purists love to hate the date. Well, the date window, that is. “It breaks the symmetry of the design,” they say. “It’s an eyesore,” they claim. And of course, “If I need to know the date, I can just check my phone.” Now, I can’t say these sentiments are totally invalid. As someone with a variety of watches and a smartphone, there are days when a clean, dateless watch is exactly what I want. But imagine you lived a hundred years ago. You’re in a sticky situation, with no calendar, no newspaper, and no human nearby to ask, and you urgently need to know the date. With nothing at hand but your only timepiece, you think, “Golly, the date on my wristwatch would sure be the bee’s knees!”

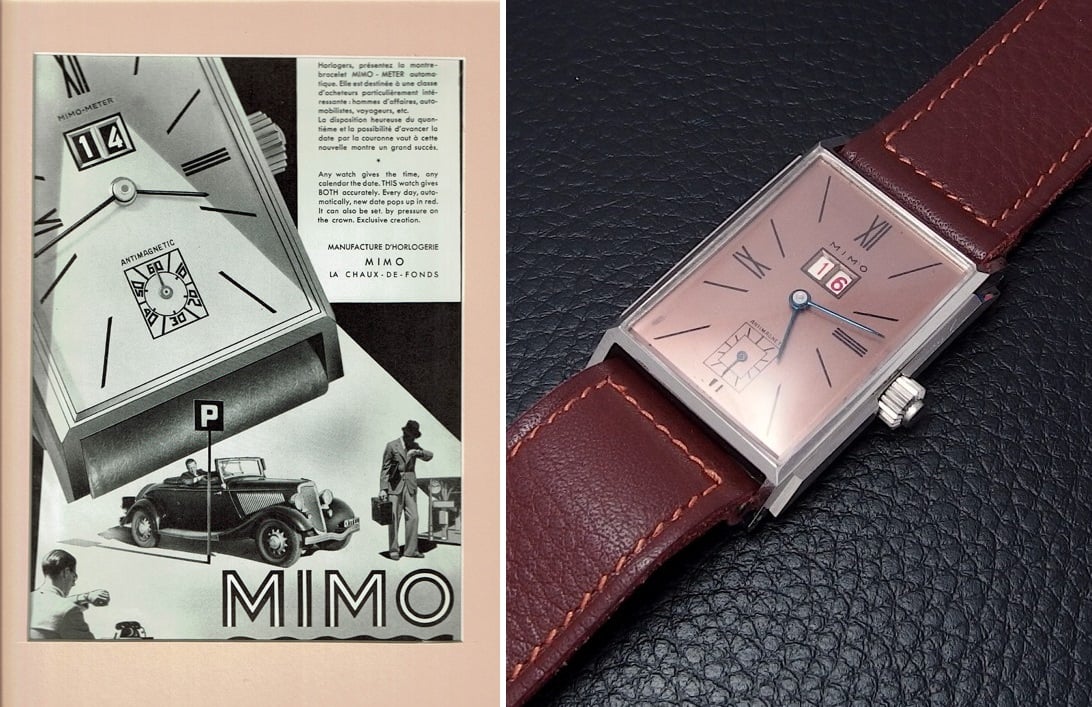

Unfortunately, you’d have probably been out of luck. Up until the 1930s, a watch with a date window didn’t even exist. Sure, there were expensive pocket watches with pointer dates long before that. But it wasn’t until January 1930 that watchmaker Otto Graef, owner of the Mimo watch company, filed for the very first patent on a date window. When Mimo came out with the Mimo-Meter two years later in 1932, it was revolutionary. Think about it — a simple aperture on the dial that displayed just one date at a time, available at a moment’s notice? I mean, it was a momentous development, a groundbreaking innovation. It was a big deal! The only problem? It was actually tiny.

Excuse me, have you seen my eyeglasses?

Certainly, Graef had good intentions when he designed the date window. How helpful it was of him to integrate such useful information into the must-have accessory of the time! As you can see, however, his first draft may have slightly missed the mark. The date aperture was absolutely minuscule, and the font on the wheel itself was only about half the size of the indices on the dial. The example above was just 22mm in diameter. So whether you’re reading this on a phone or on a computer, you’re already seeing the watch larger than it was in real life. Can you imagine the squinting such a design like this would’ve caused? Some of the other cases Mimo offered were even smaller, at 20mm or under. Thankfully, the industry was on it. Within hardly any time at all, Helvetia released a watch with a double date window.

The birth of the big date

As far as my research suggests, Helvetia was the first company in 1932 to produce what we now call a “big date” complication. The watch was powered by the Helvetia-made caliber 75A, a 15-jewel tonneau-shaped movement with an additional big date module. As you can see in one of the earliest examples above, the date was noticeably larger than on the Mimo-Meter. Each digit of the date appeared in its own window, making it far more legible. The more legible the date display, ultimately the more useful it was. And just like that, the big date complication was born.

Interestingly, though, the date did not change correctly at the end of the month. Unless manually corrected by the user, the watch would display nonexistent dates through the 39th of the month. After that, it would even display “_0”, leading to some amusing fake dates indeed! The first versions of the movement also lacked any type of quick date-correction mechanism. Therefore, the user would need to manually advance the hands around the dial and past midnight nine times at the end of every month to read “_1”. What a pain, right? To make it more user-friendly, Helvetia soon updated the movement to include a correction pusher set into the crown.

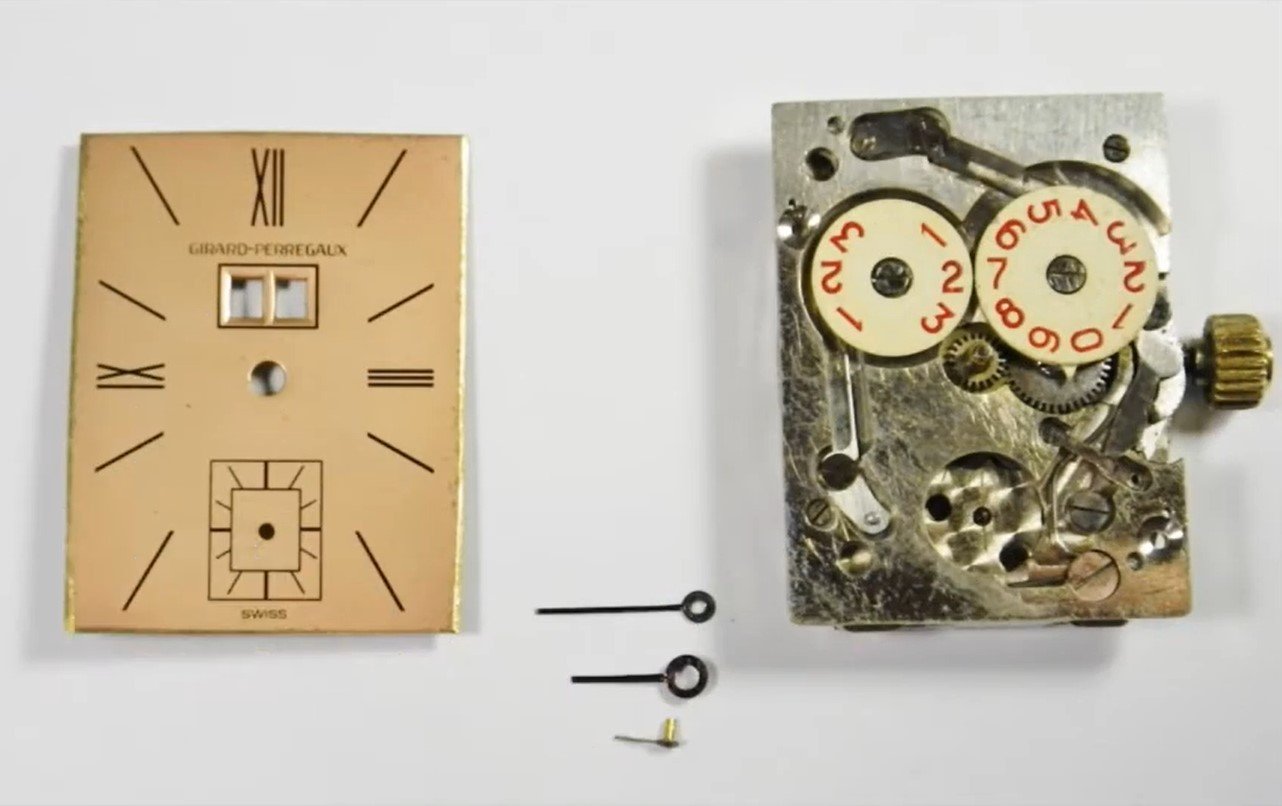

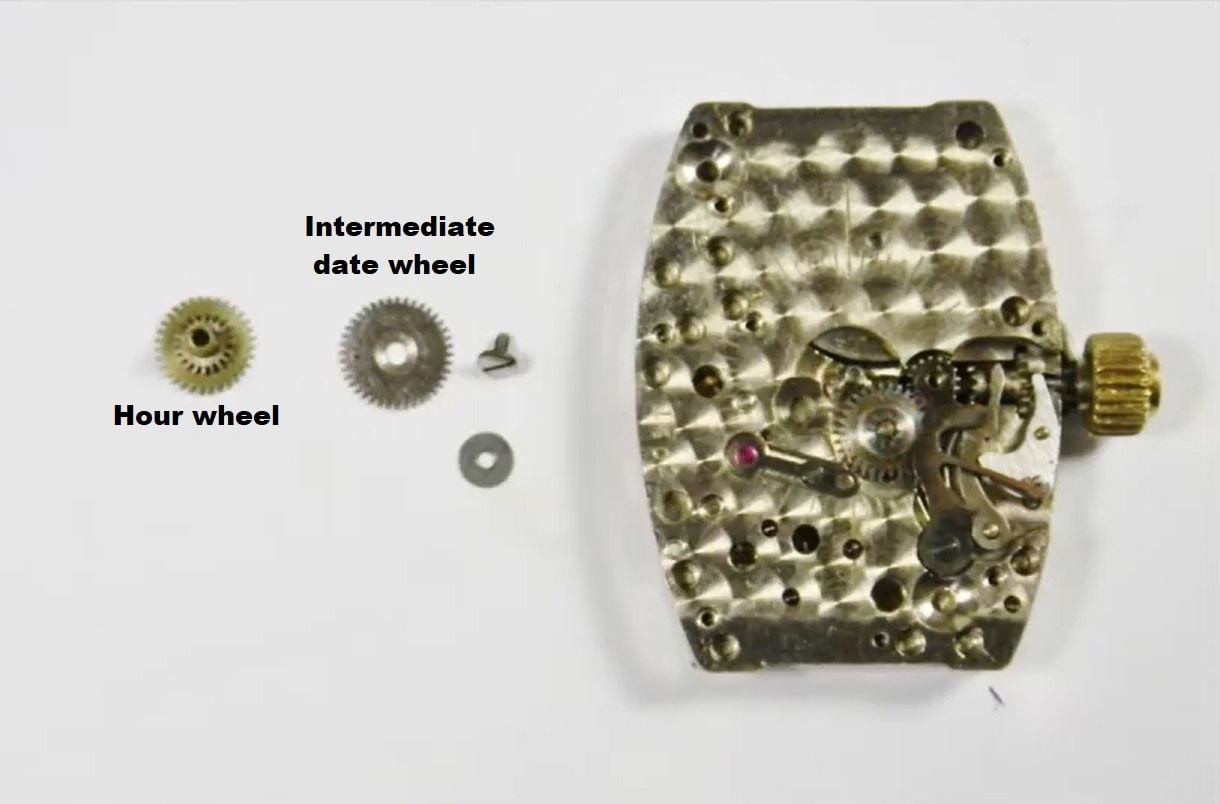

Many brands jumped on the opportunity to produce big date watches using the Helvetia 75A movement with the big date module. Before 1932 was over, brands like Ditis and Solvil produced nearly identical watches. Several other brands followed suit shortly thereafter, including Mimo and Girard-Perregaux (which Mimo owned). Above, you can see a beautiful example of a Mimo from around 1940 with the same movement. Notice the pusher set into the crown for correcting the date.

How did the first big date work?

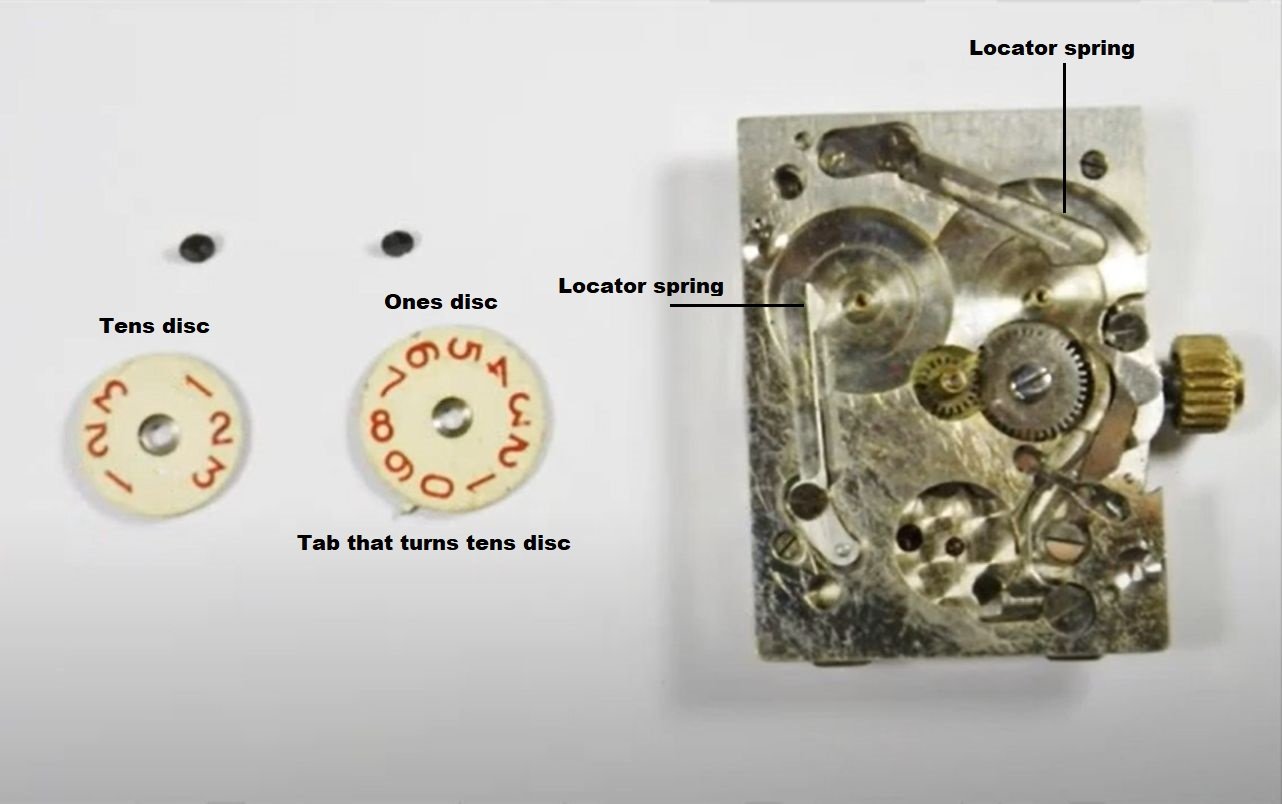

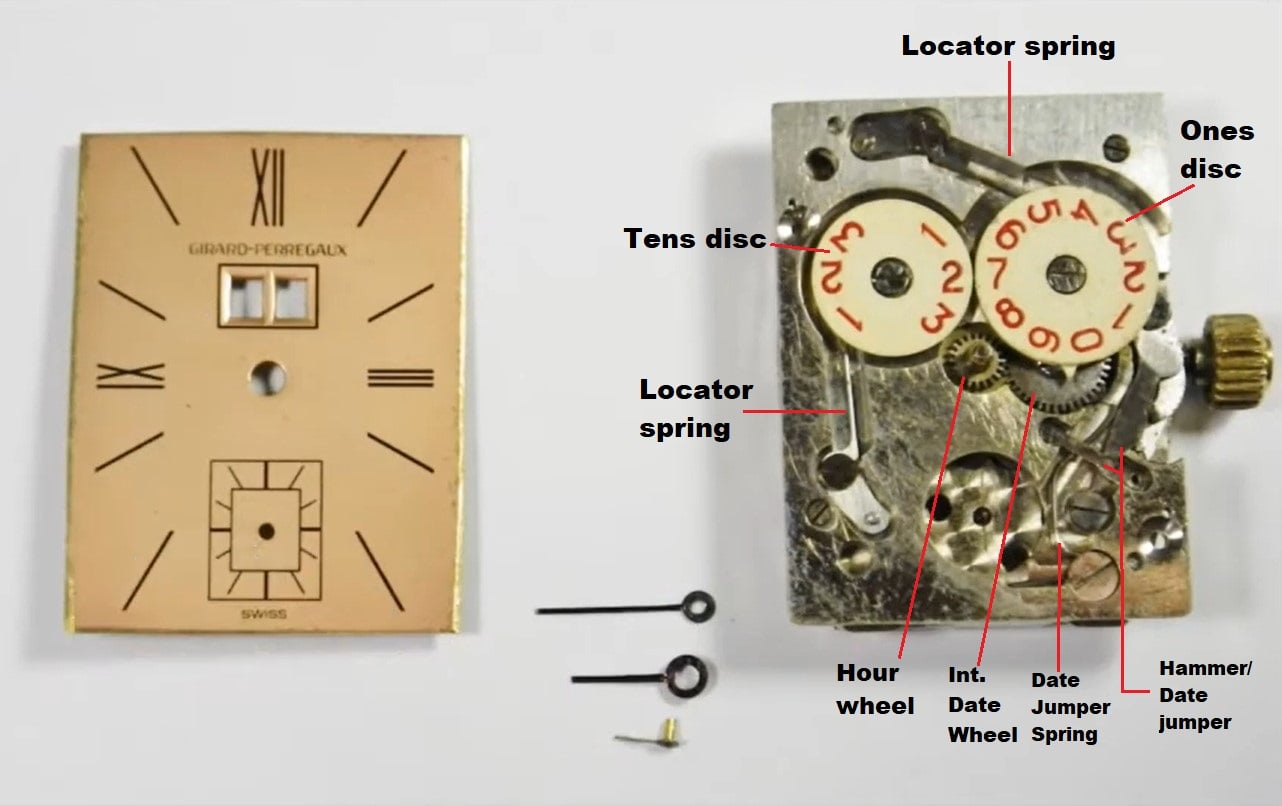

Instead of using a single date wheel, like the Mimo-Meter, the Helvetia 75A’s big date module used two smaller discs — one for the tens digit, and another for the ones digit. These discs were parallel to each other. But of course, a quick look at the Girard-Perregaux above tells us just as much. I wanted to really understand this mechanism myself and help you do the same. With the help of Fratello’s resident watchmaker extraordinaire, Rob Nudds, I got the lowdown on how this mechanism worked. It gets a little technical here, but I hope I can explain it clearly enough. If you’re not interested in the breakdown of the components and their functions, simply skip down to the “Modern big dates” section below.

You’ll notice a triangular tab protruding from the bottom of the ones disc. Once every ten days, this tab engages with the tens disc, turning it forward. Though we can’t see the underside of the date discs, we can assume that each of them is attached to a notched gear. The triangular tips of the locator springs rest in the notches, keeping the date discs in place. These locator springs quite literally locate the digits to their proper positions within the date windows.

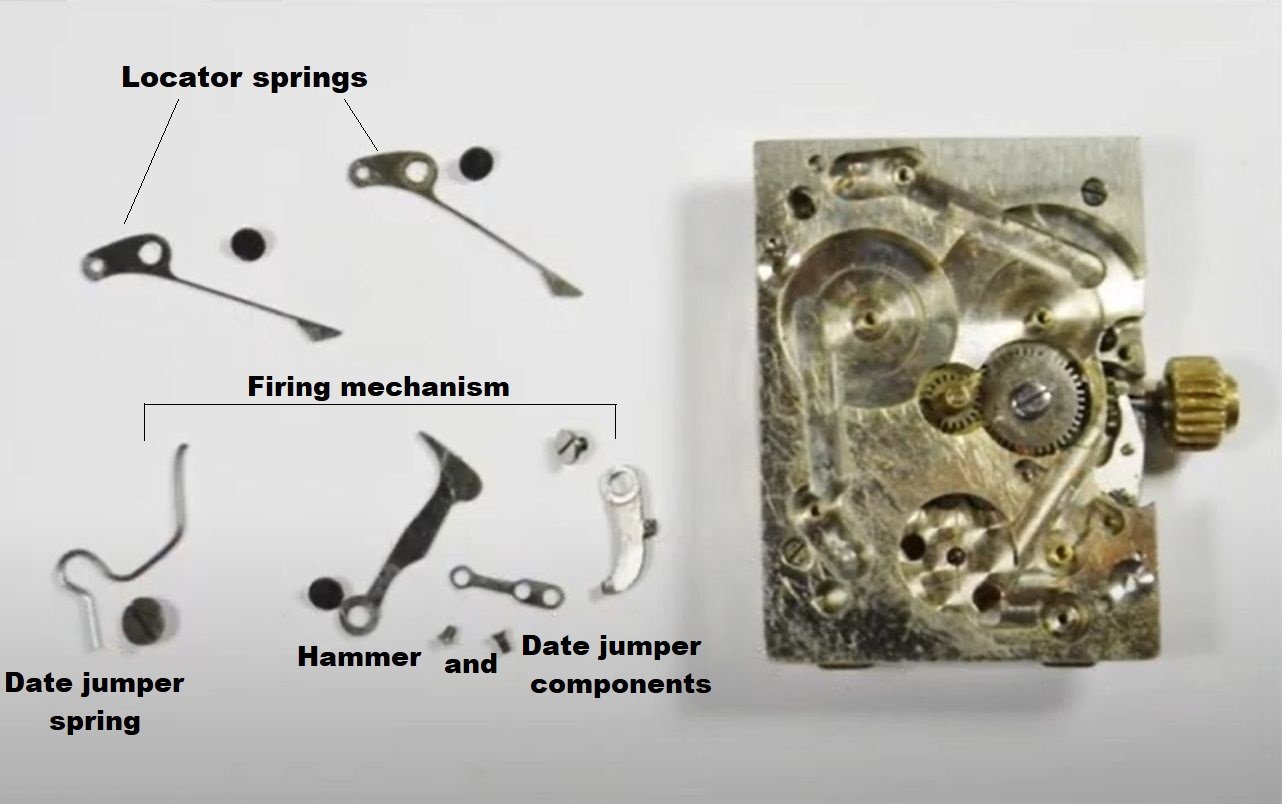

Now we know that the ones disc turns the tens disc, and the locator springs keep both discs in place. But what turns the ones disc itself to advance the date at midnight? Well, that is the firing mechanism. A firing mechanism is a key component in virtually all date window complications. On this particular movement, the date jumper spring begins to store energy a few hours before midnight. When the spring finally has enough energy and tension, it releases it via the hammer and date jumper components. Basically, the tip of the hammer pulls the gear underneath the ones disc, advancing it forward.

Where does the energy come from?

The energy required to load the date jumper spring and pull the hammer comes from the hour wheel. The hour wheel turns once every 12 hours and holds the hour hand. The hour wheel transfers the movement’s energy through (what appears to be) an intermediate date wheel. This meshes with the gear on the ones disc itself. It works in tandem with the firing mechanism to deliver enough energy to advance the date.

To recap

Now that you’re (hopefully) familiar with all of the parts and their basic functions, let’s look at the mechanism one more time in its assembled and labeled form to quickly recap. The hour wheel drives the intermediate date wheel, which meshes with a gear under the ones disc. The date jumper spring and hammer/date jumper store up energy from these wheels, and release it around midnight to pull and turn the ones disc. Every ten days, a tab on the ones disc pushes the tens disc forward one position. The locator springs hold both date discs in the proper position to display the numerals in the date windows. The movement must be manually corrected at the beginning of every month.

Modern big dates

The past 90 years have brought with them both advancements in horological engineering and better manufacturing processes. Thanks to that, movement manufacturers today not only use more refined date jumpers, but also a whole variety of big date mechanisms. Due to the restraints of time, sanity, and personal ignorance, I won’t explain how each and every mechanism works in depth. I would, however, like to give some examples of what the watch industry has to offer today when it comes to the big date complication.

Parallel discs

The parallel double-disc big date still exists today. While some movement makers integrate it into the movement design, most take the form of modules, such as those by Dubois Dépraz. Like the Helvetia 75A module, some modern modules give a big date to a base caliber without a calendar function. Others, like the module in the Cartier Pasha seen above, sit on top of a base caliber with a pre-existing calendar.

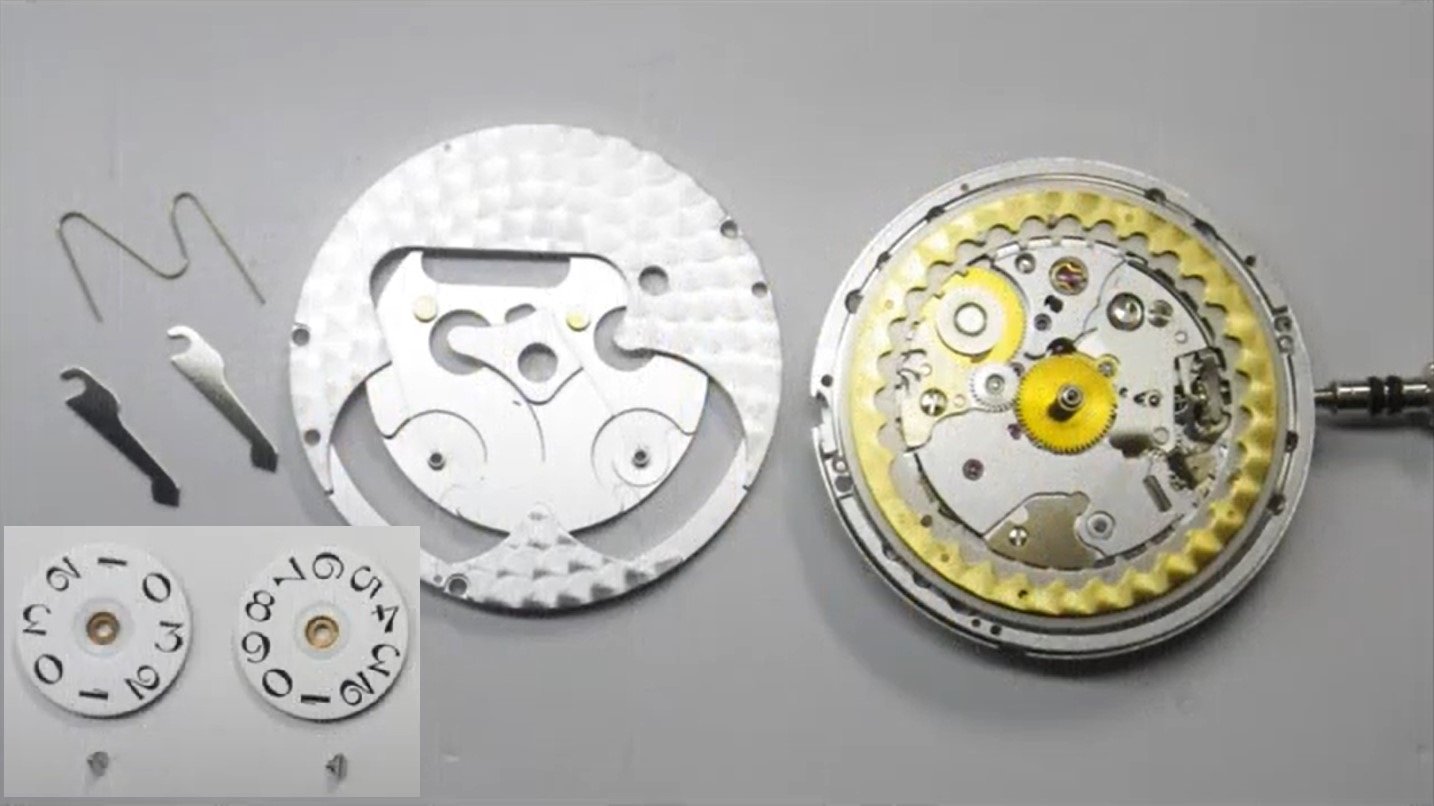

Looking at the ETA 2892-A2 on the right in this image, you’ll notice a golden wheel running around the perimeter of the movement. This is the date disc, with the digits removed. The module on the left is made up of a plate, a spring, two locator arms, two big date discs, and the screws that hold them down. This module works in conjunction with the basic calendar function to convert the standard date display of the 2892-A2 to a big date at six o’clock.

The Chopard 150 All-in-One is an example of an integrated big date display. Chopard designed and built the 516-component 05.01-L movement from the ground up, giving the brand the ability to work the big date display into its original design. Therefore, the caliber has all of the necessary gears, levers, and springs for the big date built into it already.

Overlapping components

Several brands use a system of overlapping discs or similar components to achieve their big date displays. Perhaps the most famous of these is A. Lange & Söhne. The brand first brought its “outsize date” display to market in 1994 on the Lange 1, and it has gone on to become a nearly inseparable part of Lange’s design language.

Rather than two full discs that overlap, the L121.3 caliber above uses one “units disc” and an overlapping “tens cross”. This design allows for a much larger date display than would be possible with either a single date disc or the parallel date discs we saw earlier. In my opinion, the only downside to this design is that the tens cross is on a visibly higher plane than the units disc. This is very noticeable from the dial side. Both the units disc and the tens cross utilize program wheels and a train of gears to advance the date. If you’d like to watch an animation of how it works in more detail, click here to watch A. Lange & Söhne’s official video.

Other variations of overlapping discs

Jaeger-LeCoultre also uses overlapping discs in its big date displays. The Reverso Grande Date with JLC caliber 875 uses a much larger units disc than the Lange, as well as a square tens disc.

The Blancpain caliber 6918B, found in the Fifty Fathoms Grande Date, also uses overlapping discs. This setup is closer to the Lange’s than JLC’s, with a somewhat cross-shaped tens disc overlapping a larger units disc. Like the A. Lange & Söhne and Jaeger-LeCoultre designs, the big date display is split into two windows separated by a bar.

Perhaps the ultimate in cleanliness when it comes to overlapping big date discs is Girard-Perregaux’s solution. Seen here in the GP Vintage 1945 XXL Large Date Moon Phase, caliber GP03300-0062 uses a clear sapphire units disc and an opaque tens disc. The clear sapphire disc overlaps the opaque disc so much that both disc’s normal positions can be reversed. As a result, two large numerals can appear in the same date window with no visible seams. From most angles, the digits even appear to be on the same plane.

Disc-in-disc displays

Some companies produce big date displays with the tens disc placed inside the ones/units disc. This solves the problem of the units being on different planes while still keeping the big date mechanism compact.

The Glashütte Original SeaQ Panorama Date shows how clean this big date display can be. From a distance, the seam between the discs is hardly visible at all. Some enthusiasts also prefer GO’s Panorama Date over Lange’s outsize date for its inclusion of 0 on the tens disc. I also think it balances the date display better than an empty square on the 1st through 9th of the month.

Zenith also produces a disc-in-disc big date display, visible here on its Chronomaster El Primero Full Open. In this particular execution, the numerals on the date discs themselves are have been cut out completely, with only the current date highlighted by a red piece underneath it.

Full-size disc-in-disc displays

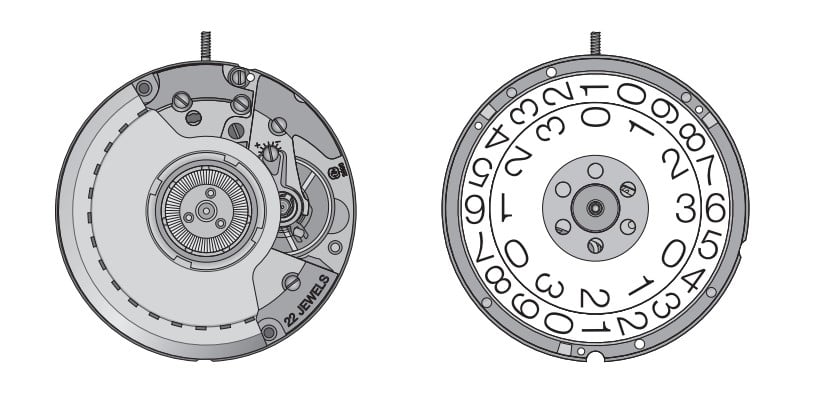

Some watches, such as the Breitling Galactic 41, feature a big date display at the three o’clock position. Often, these watches utilize the ETA 2896 movement. This caliber comes stock with two large discs that cover most of the dial side of the movement.

The ones/units disc is basically the size of a standard date wheel, but with fewer and larger teeth. The tens disc sits inside of it, geared to make one full rotation every month.

Stacked date discs

The final big date solution that comes to mind is the one used by H. Moser. Movements such as the HMC 100 in the Venturer Big Date use two full-size date discs stacked on top of each other. The top disc displays numbers 1-15 and the bottom one shows 16-31. When the top disc has completed its 15-day cycle, the bottom disc begins to turn. This big date solution, while physically large, is a departure from the standard concept of the complication. But that’s Moser for you!

One of the most useful, practical complications

Regardless of purists’ opinions on the aesthetics of a date window, for most people in the real world, the date complication is an extremely helpful thing to have on a watch. Whether we’re signing important documents, checking how many days are left until a loved one’s birthday, or planning the rest of the week ahead, the date affects all of our lives. And these days, while you always could take out your phone to check the date, why bother if you have all the info you need right on your wrist? Since the early 1930s, the date complication has been bringing real convenience to people’s lives. I feel that the big date does an even better job, not only making the date easier to read, but also making its display all the more balanced and attractive without any need for a magnifier.

Now I’ll throw it over to you. What do you think of the big date complication? Do you love it, hate it, or find yourself somewhere in the middle? Also, did you find this article interesting or helpful? If so, let me know in the comments. Thanks for checking out this installment of How Watches Work!