Book Review: The History Of The Seiko Alpinist + 5 Sports Speed-Timer

When an early Seiko Alpinist 14041 resurfaces in an auction in Japan, you can bet that there will be a fiery battle over who gets it. But did you know which model came first, the black-dialed or the white-dialed one? We found an answer in Sadao Ryugo’s new book on vintage Seiko watches.

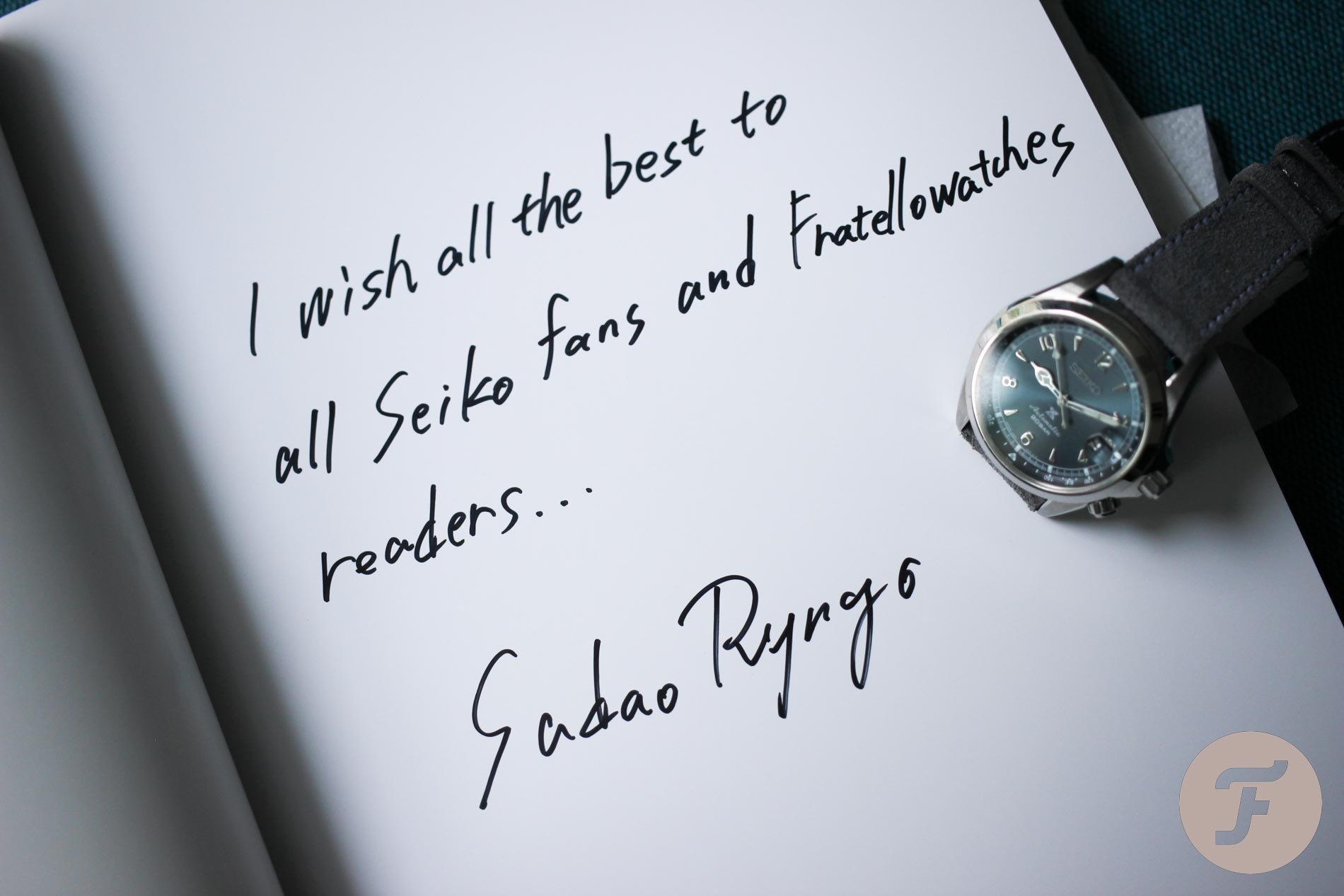

“Seiko’s first sports and mountaineering watch was launched in December 1959. It was a robust watch with a screw-on back cover which was coated with an unprecedently large amount of luminous paint. In other words, it was the birth of Seiko’s first luminescent waterproof sports watch, the Laurel Alpinist,” writes Sadao Ryugo in the introduction to his latest book. He isn’t new to the Fratello readers. Two years ago, he published a book, The Birth Of The Seiko Professional Diver’s Watch.

Sixty pages about the Seiko Alpinist

Mike was lucky enough to grab a Laurel Alpinist before their prices went bonkers. I decided to focus on the later Alpinist reference J13079, which, I learned from the book, debuted in May 1963. Besides the sector dial and unusual seconds-hand tip, I really liked the 24-hour dial markings that you can only find on this Alpinist reference. What really puzzled me was the case back, which was different than I expected it to be. Had someone swapped it? “The old and new dials and cases are sometimes mixed when switching from one to the other,” Sadao Ryugo explains, indicating that finding the J13079 dial in an 85899 case isn’t unusual.

Daydreaming imagery

The book’s big A4 format offers a lot of space for impressive and suggestive images. As in the previous book, all of the pages have a black background. You need to get used to a lot of reflections when reading, but it’s not a big thing. The black layout is pretty unusual and makes the watches really pop. I loved page 20, showing the J13033 Champion Alpinist Type 1 from 1961, planned and designed by Daini Seikosha. It was the second-generation Alpinist that came with an unreal protective strap. I have never seen it, but it looks like there is at least one real example that has stood the test of time.

The book’s structure is in line with the previous one. Each model generation is followed by a tour of the different references — around 10 Alpinist models in total — with a lot of pictures and a short description of each of them. Each chapter ends with a summary table comparing the key specs of each reference and some technical drawings.

After 30 pages on vintage Alpinist watches, there is an interview with Jun Tanaka, “the man behind the revival of Seiko mechanical watches.” He joined Seiko as a watch designer in 1980, and ten years later, he pushed persistently to manufacture mechanical watches. This led to the debut of the revived Alpinist in 1995.

“Youngtimer” Alpinist

Some of my collector friends get so excited when some of the late-’90s or early-2000s Alpinists resurface. I have to admit that I was never really into the modern Alpinist, and I was pretty lost in all the references. This book, however, helped me to understand them a bit more. One of the surprising facts I learned was that Seiko actually used a microfilm drawing of my beloved J13079 as a reference for the revived Alpinist.

New chapter

The next part of the book is devoted to the journey around the development of Seiko’s first chronograph wristwatch, the Crown Chronograph. In particular, the interview with its developer Mr. Toshihiko Ohki is very enriching.

Thirty pages on the 5 Sports Speed-Timer makes for very nourishing reading. You will find all the differences between the 6139-6010 JDM, 6139-6000 JDM, 6139-6009, a special Sony-branded model, and plenty of others, including the 6139 for French, Italian, and British markets. I was also happy to find more information on the 6139-7060, which I bumped into recently and really liked its green sunburst dial. Anyway, just when you think the parade is over, there is another spreadsheet waiting with a bunch of other 6139 Speed-Timers.

There were more than 100 types of Speed-Timers for the Japanese domestic market only. If we included export models, we would get to 300 in total, according to Sadao Ryugo. The next part of the book maps caliber 70xx Speed-Timers, with a bit of surprise right at the beginning. For the first time, I spotted the so-called “Rally Meter” reference 7015-7010.

All of Suwa’s 6139 and 6138 chronographs sported a standard tachymeter ring. So one way for Daini to distinguish itself was for the 70xx to feature rotating dial rings that could perform functions unavailable on the 6139. The logarithmic scale on the Rally Meter rotates around the fixed scale. Its function is to calculate the speed and distance traveled during the rally. Nice.

Last thoughts

If you want to categorize your thoughts and knowledge around the Seiko Alpinists or Speed-Timer, you will hardly find a better source, at least in English. The book is bilingual, showing Japanese and English text next to each other. The table of contents is pretty detailed and uses watch references as a pointer. This comes in handy if you do research and want to check a specific reference. Sadao Ryugo is active on Instagram as @mrseikosha, so feel free to reach out to him about the price and availability of his book in Europe and elsewhere. The previous one is already available as a Kindle edition on Amazon. Happy Christmas reading!