The Story Of Lume — Part One

Who can resist the warm glow of luminescent material on a watch dial, the mystical greenish glow of hands, indices, or even entire dial surfaces? Whether the function is telling the time at dusk at home or an expedition through the mountains, it’s like magic, inspiring heavy-hitting hashtags like #lumeshot, #lumecolors, and #lumebattle. If you’re into sports and divers’ watches, it is one of the signs of quality you’re after, so read on for part one in the story of lume.

I’m starting this two-part story while on holiday by the sea with a tough beater and a Seiko Marinemaster 300 in tow. And in a throwback to my youth, I’m charging the latter on the nightstand to tell me the time as I wake up in the too-warm hotel room at 3:00 AM to adjust the aircon. From handling mundane tasks like this to indicating the life-saving minutes of air left in your tank when diving, we take lume for granted. But how does it work, and when did the first glowing watch index appear?

The origins with Albert Zeller of RC Tritec

I was lucky enough to have a long chat with the CEO of RC Tritec, Albert Zeller, leading to a deeper understanding of luminescence. Unless you’re deep down the horological rabbit hole, the name RC Tritec won’t mean much. But the trademark Swiss Super-Luminova does. Indeed, it is the mainstay of powerful lume. Its iterations like C1 and C3 along with custom applications and solid luminescent materials are what make most wristwatches glow. I’ll let Albert, whose company I had for a few hours, introduce RC Tritec.

Starting off with an insight into the company and the brands it works with, Albert points out the Panerai dial on a poster behind him, telling me, “Talking about brands, it’s basically every brand that is not based in Japan. Some officially show the collaboration, and some prefer to give their products their own name.” This confirmed my suspicions about a big market share.

The beginnings of radioactive luminescence

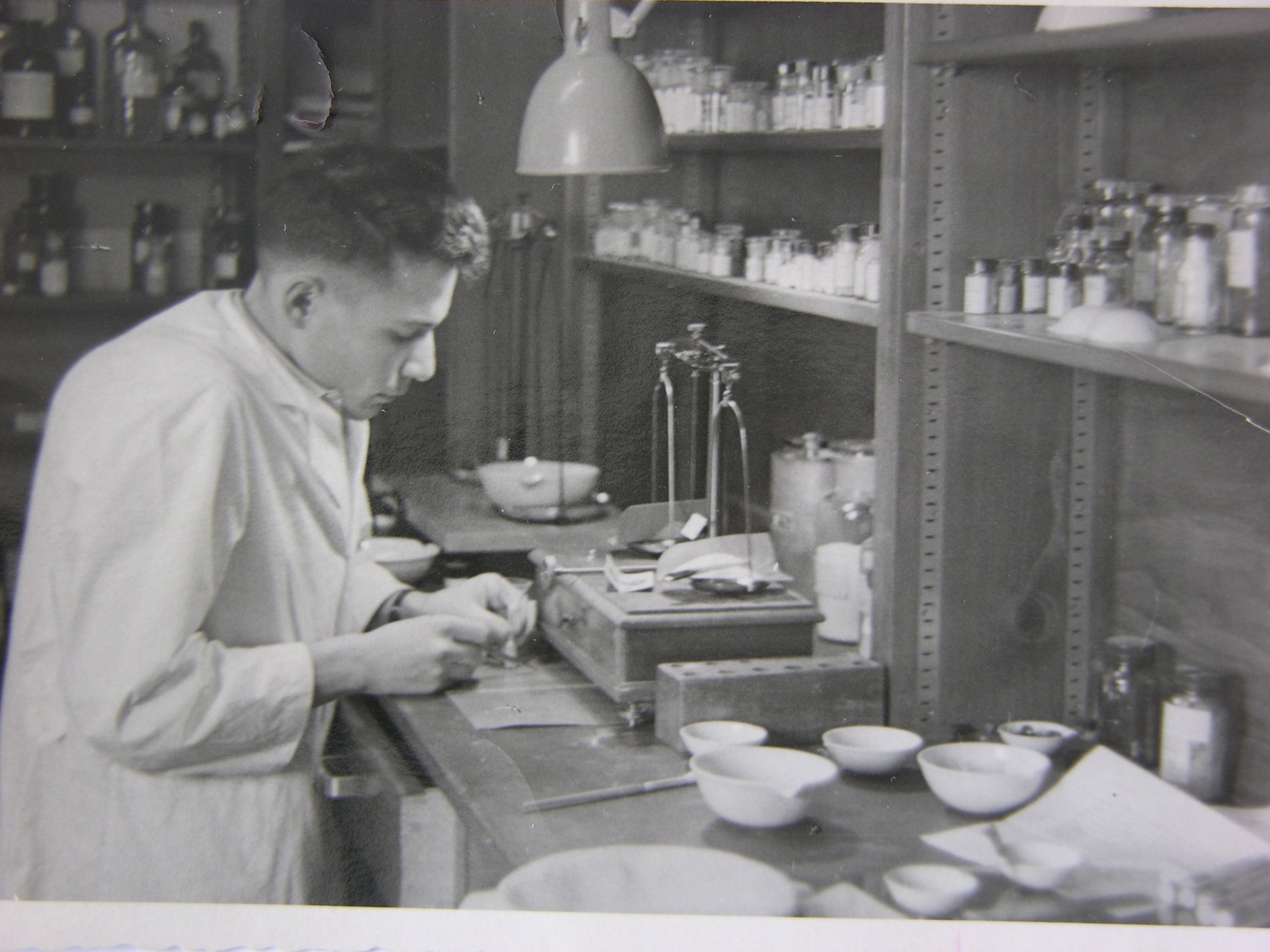

If my memory serves me right, this company existed from the birth of luminescence, long before the strong but harmless lume of today. Albert says, “Basically, RC Tritec is the main manufacturer of these materials. It all started with my great-grandfather, in 1934 to be exact. He was a pharmacist in a family who was producing herbal medicine, what we now know as Phytopharma. There were 13 children in his generation, so Albert decided to strike out on his own. Yes, by the way, his name was also Albert Zeller. All the generations have the same name; call it tradition or lack of creativity, but that’s something we’ll have to discuss with my father.”

Albert tells us about the birth of lume as we know it. “My great-granddad wanted to bring something new to the market, a high-tech product. Back in the 1930s, radioactivity was at the forefront of innovation, like today’s blockchain, nano surface treatments, and so on.” But as Albert tells us, his great-grandfather did not plan on using this to facilitate time checks in the dark.

A radioactive, medicinal start

Not many of us know the pharmaceutical beginnings of RC Tritec, but Albert sheds light on the story: “Back then, people found out that if you could fill the top of a needle with radium-226 and inject it into a tumor, everything around the tip of the needle would get radiated. This was the first puncture-based cancer treatment.” As the top tech of the day, people thought that with radium’s cancer-curing abilities came health benefits. Albert goes on, “My great-grandfather started with drinking glasses with radium in the bottom to irradiate the water, imbibing it with untold health benefits. From a scientific point of view, this is complete nonsense. But if you believe in something strong enough, the effect is psychosomatic.” But after a while came the breakthrough with luminous materials.

Luminous materials and their unhealthy conclusion

Albert tells us his great-grandfather started to diversify, keeping the radium focus. “My great-grandfather worked with a combination of zinc sulfide, a luminous crystal, mixed with radium-226. This combination led the zinc sulfide to glow the entire night. You had radium as a source of the energy, and the radiation led the zinc sulfide to glow and emit light. Albert Zeller the elder wasn’t the first, as seven other companies in Switzerland were producing similar materials.”

Albert tells us about the start of radium applications. “In the US, there were big brands using radium and the application of luminous pigments was done by brush. It was mainly ladies using the brushes, and then when the brush wasn’t sharp anymore, they licked it.” Today, we know that even being close to radioactive materials causes cancer, not to mention ingesting them.

Could a sustainable alternative be found?

Radium was believed to have health benefits due to its effects on cancer. But it was discovered to be an alpha-emitting material, so it did not have any future because it was actually harming people. The company looked for another solution along with other producers to find a healthy, sustainable alternative. Albert continues, “Our company looked for suitable materials and found tritium as a suitable candidate. We were the first to combine tritium with zinc sulfide, leading to a similar process while emitting fluorescent light in the dark. But tritium has a hydrogen base. It’s a gas, so you cannot open the bottle and hope that it’ll stay around the zinc sulfide. The basis of our success was attaching the tritium to styrene, polymerized on top of the zinc sulfide. With this slightly radioactive coating, the tritium activated the pigment to make it glow.”

Was tritium the lasting solution?

Albert continues, “The radiation was not measurable anymore. Tritium can only be measured in liquid scintillation, so people thought that if it’s not measurable, it should not harm anyone. But tritium has a half-life of 12 and a half years, so after that, you’re at half of the performance. In reality, the half-life is shorter still, so after five to 10 years, you’ve already halved the performance.” This is something we all recognize from vintage watches with the “T < 25” at 6 o’clock and the desirable, creamy lume that has decayed to the point of non-function. But it sure looks good on a tropical-dial Sub!

Stay tuned for part two, Fratelli, and let us know what your favorite type of lume is in the comments!

Find and follow me at @thorsvaboe