Who Was Abraham-Louis Breguet? — Get To Know The World’s Most Famous Watchmaker

You know the brands; now it’s time to learn about the people who founded them. We will get up close and personal with names you know so well without really knowing them, if you know what I mean. In this new series, Fratello will introduce you to the people behind famous brands and their creations. The first installment features the founder of Breguet, a Swatch Group brand celebrating its 250th anniversary this year, but we will also introduce you to famous watchmakers of today. First things first, though — Abraham-Louis Breguet. “The most famous watchmaker of all time” is one way to describe him, but it doesn’t tell his life story. Hopefully, we will satisfactorily answer the question, “Who was Abraham-Louis Breguet?”

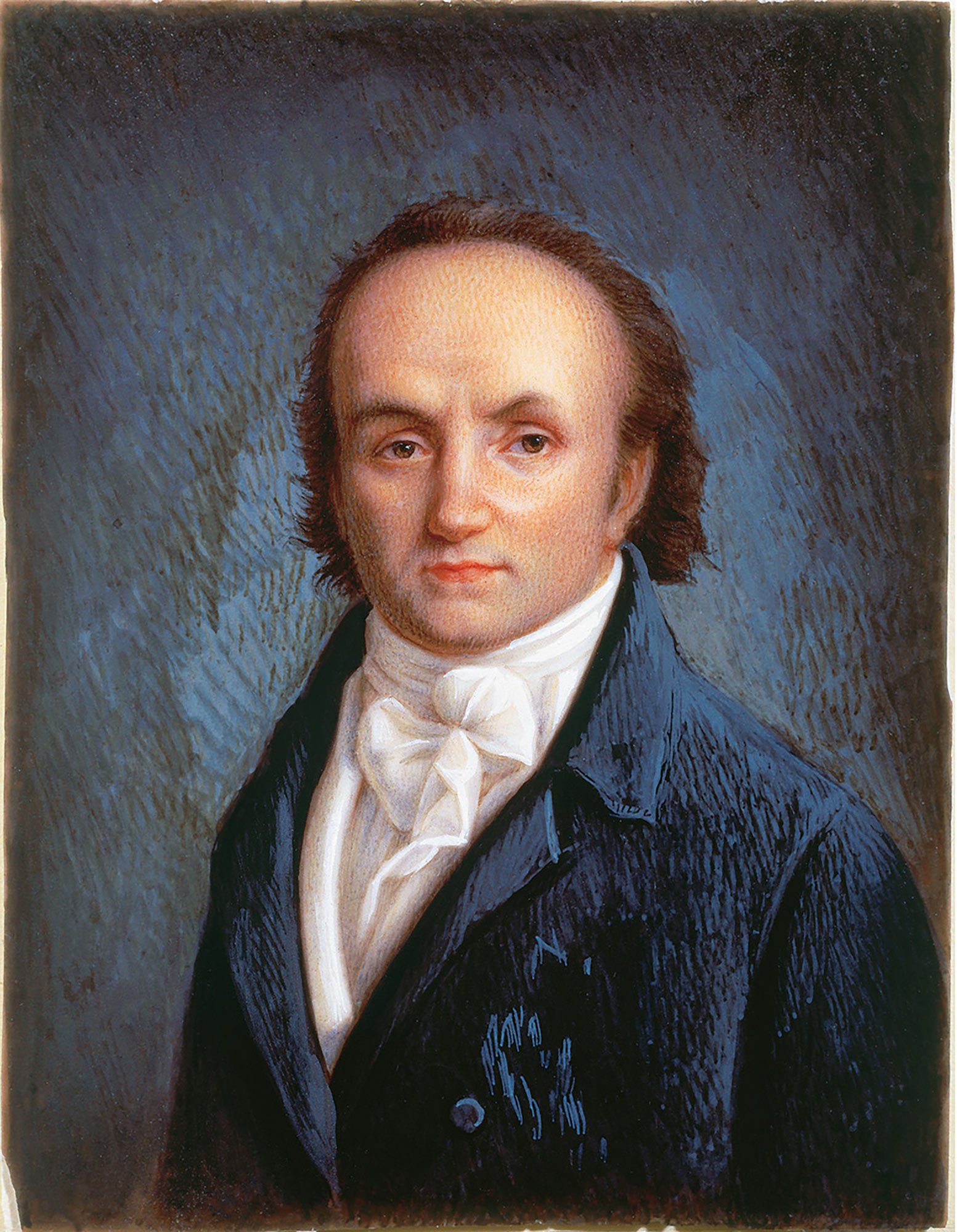

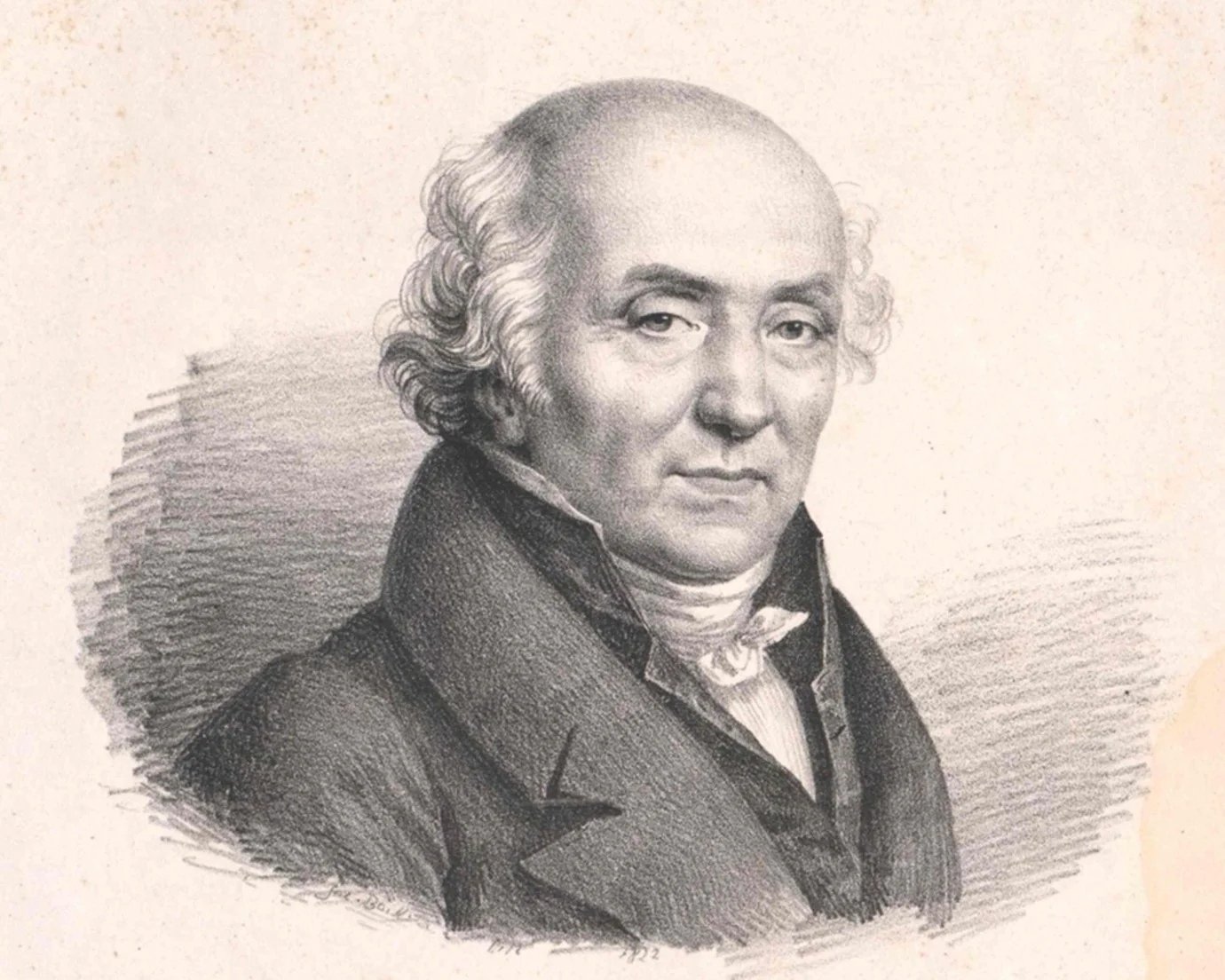

This story doesn’t tell about the history of Breguet as a manufacturer. Instead, it focuses on the brand’s founder, Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747 Neuchâtel, Switzerland – 1823 Paris, France), an outstanding scientist and technician. He devised numerous inventions within horology, such as the tourbillon, the first wristwatch, and Breguet’s “pomme” hands. He initiated the neo-classical style in watchmaking; his creation of a refined and legible design became the trademark of Breguet and many timepiece brands since. Swatch Group acquired Breguet in 1999, and the house’s rich heritage and innovative spirit are reflected in more recent inventions, such as the silicon balance spring and the magnetic pivot. Today, the brand resides in the Vallée de Joux, the famous Swiss watchmaking valley, some 75 kilometers southwest of Neuchâtel, the birthplace of Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Who was Abraham-Louis Breguet? — The early years

Abraham-Louis Breguet was born to Jonas-Louis Breguet and Suzanne-Marguerite Bolle, descendants of French protestants who fled catholic France for the safety of Switzerland in the late 17th century after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In 1758, when Abraham-Louis was only 10, his father died, and his formal education ended two years later. His mother subsequently married Joseph Tattet, a member of a prominent family of watchmakers with a showroom in Paris. At first, young Breguet wasn’t interested in the craft, but eventually, he embraced it enthusiastically.

In 1762, at age 15, he was apprenticed to an unknown master watchmaker in Versailles, then the hub of France’s finest horological talent, closely tied to the royal court. He also attended evening classes at the Collège des Quatre-Nations — also known as the Collège Mazarin after its founder, Louis XIV’s minister Cardinal Mazarin — where he excelled in mathematics and physics. Later, renowned watchmakers Ferdinand Berthoud and Jean-Antoine Lépine took him under their wings, and he impressed them with his skill and intellect.

Kings, queens, and dukes

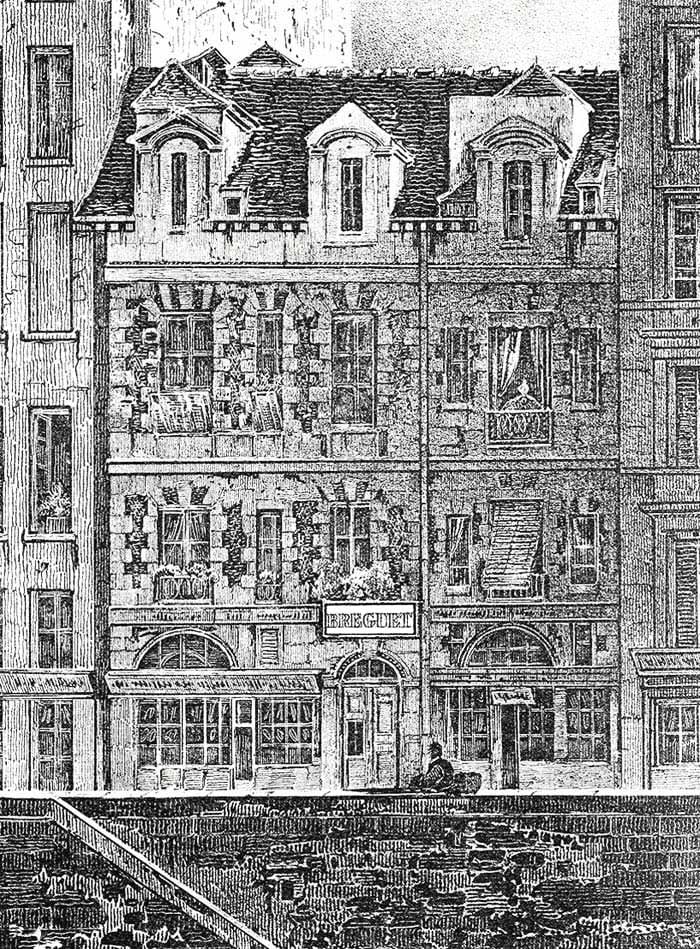

Abbé Marie, Breguet’s mathematics teacher and mentor at the Collège Mazarin, introduced him to the dukes of Angoulême and Berry, who then introduced him to King Louis XVI. The king’s fascination with mechanics soon brought Breguet numerous royal commissions. The world’s first automatic watch stems from that period. It didn’t use a rotor; the oscillating weight jumped up and down around a pivoting arm. The first Perpétuelle was sold to the King’s cousin, the Duke of Orléans, in 1780, five years after Breguet opened his watchmaking workshop at the Quai de l’Horloge on the Île de la Cité in Paris, funded by commissions from wealthy and influential patrons. Queen Marie-Antoinette was also a client, and Breguet’s connection to the king and queen greatly enhanced his reputation and success.

The illustrious Breguet no. 160, the “Grand Complication,” more commonly known as the “Marie-Antoinette” or the “Queen,” was not commissioned by the queen. Rumor has it that Swedish count and admirer/lover Hans Axel von Fersen ordered it. Breguet’s 160th creation was an 823-part pocket watch containing every watch function known at the time. The work started in 1783 and was completed 44 years later by Breguet’s son, Antoine-Louis, four years after his father’s death and 34 years after the queen’s.

The watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet

Opening his atelier marked the start of Breguet’s independent career as a watchmaker, allowing him to explore new ideas and shape his distinctive style. In the years that followed, his workshop grew into a renowned center of horological innovation and craftsmanship, establishing his reputation not only as a master watchmaker but also as a pioneering inventor. He invented many things during this period, including the blued pomme hands.

“What he did was completely new,” Vice President and Head of Patrimony Emmanuel Breguet told me some time ago at the Breguet Museum on the first floor of the brand’s boutique on the prestigious Place Vendôme in Paris. “The hands are long and slender rather than baroque. The absence of rich ornamentation was radically new for that period. Breguet introduced a radically new aesthetic. He created clarity, space, and light by rotating the slender hands across a white dial, which was absolutely revolutionary.”

Exile in Switzerland

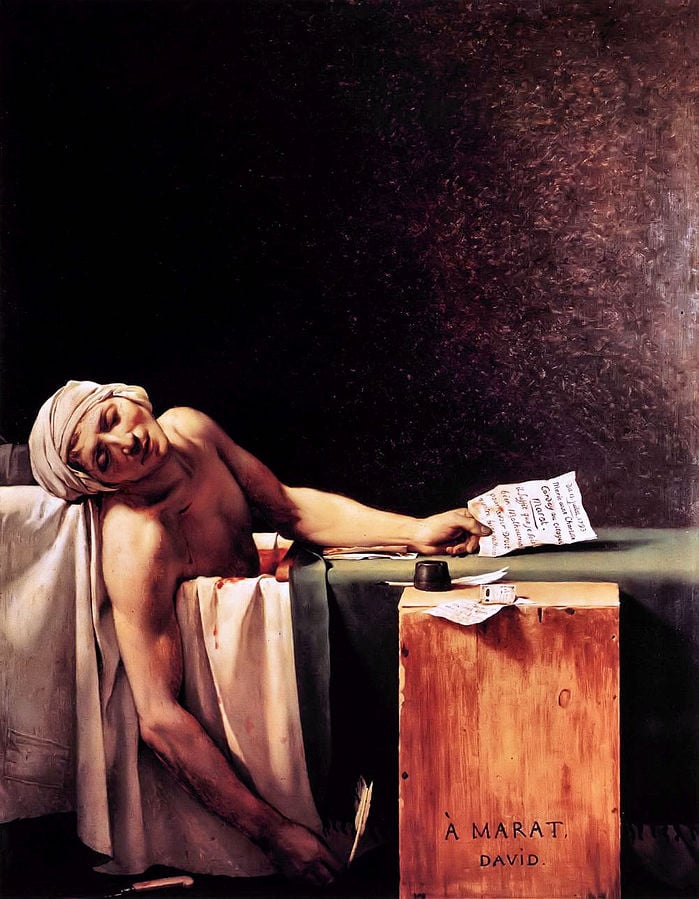

Although Breguet worked for the court, he was a liberal and a member of the Jacobins, the most famous political club during the French Revolution (1789–1799). However, he condemned the Reign of Terror, which led to his exile in 1793. The guillotine was awaiting the watchmaker, but he fled the country with a safe-conduct pass arranged by Jean-Paul Marat, a prominent Jacobin and agitator. Marat, like Breguet, hailed from Neuchâtel. The two had a complex friendship and were connected by Marat’s sister, Albertine, who supplied watch hands to Breguet’s workshop.

One day, Marat and Breguet were visiting a mutual friend in Paris when an angry royalist lynch mob gathered outside looking for Marat. To save his friend, Breguet disguised Marat as a woman, including a powdered face and rosy cheeks. They waited until nightfall and then calmly walked out arm in arm, merging into the crowd, after which Marat escaped to safety. In 1793, however, Breguet couldn’t help Marat when he was stabbed to death in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday, one of his many political enemies.

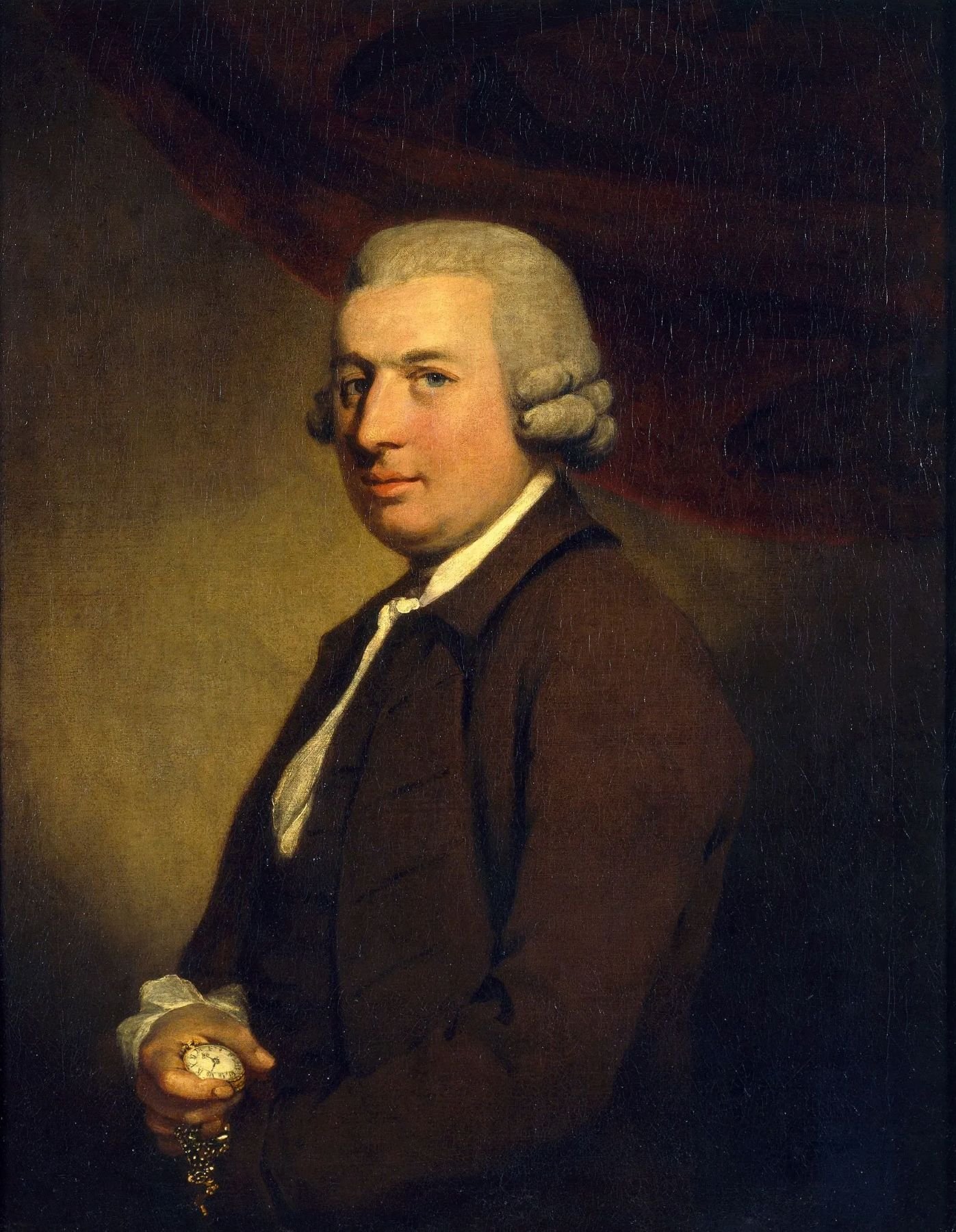

The friendship between Arnold and Breguet

Before and during his exile, Breguet frequently traveled to London in the 1780s and 1790s. He became close friends with fellow chronometer maker John Arnold. Later, this relationship extended to their sons, with John Roger Arnold working for Breguet in Paris and Louis-Antoine Breguet working for Arnold in London. Both Breguet and Arnold were genius inventors who influenced each other. For instance, Breguet incorporated ideas from Arnold into his dial designs. And then, of course, there’s the tourbillon. Some say Breguet could not have developed the mechanism without Arnold and that the Englishman should be credited for co-inventing it. The two watchmakers probably talked about the concept, but nothing was left in writing. Something did happen in 1809 that could serve as an indication that Arnold played an important role, but that’s for later.

Back in Paris

Breguet’s exile didn’t sit well with him. He worried about his employees, his house, and his workshop. And although his friends, who had fled to London, pleaded with him not to return to the still-unstable city but to the safety of England, he returned to Paris in 1795, at the age of 48. Determined and fearless, he reclaimed his house and restored his workshop on the Quai de l’Horloge. But the city was a wreck, both emotionally and economically. The Terror has decimated the aristocracy, watchmaker Breguet’s most important clients. In their place, however, new social classes were forming. This wealthy bourgeoisie and the new Napoleonic aristocracy became Breguet’s new clients — indeed, “nouveau riche.”

He also found time to marry Cécile Marie-Louise L’Huillier, the daughter of an established Parisian bourgeois family. Her dowry probably provided part of the capital required to establish the business. Breguet then had to find a new clientele, but more on that later. First, we look at the tourbillon, which was arguably Breguet’s biggest invention.

The mechanism had been on his mind when he returned to 51 Quai de l’Horloge. During his exile, Breguet studied diligently and met with numerous Swiss watchmakers in the Jura Mountains, from Geneva to Neuchâtel. The driving force behind the tourbillon was the challenging quest to achieve the most consistent movement possible. Breguet’s deep understanding of the laws of physics made him realize how positional changes influence a movement’s accuracy. A drop in accuracy was particularly noticeable when pocket watches were held vertically. He figured out gravity was to blame and started thinking of a way to eliminate its influence. He succeeded by placing the balance and escapement in a rotating cage that fully rotates around its axis once per minute.

The enlightened tourbillon

“Tourbillon” is the French word for “whirlwind,” but there’s more to the name than that. It is plausible that Breguet arrived at the name from a more astronomical and enlightened perspective. During his lifetime, the academic Breguet studied the work of philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596–1650) and Diderot’s famous Encyclopédie, the first volume of which appeared in 1751. In the standard works of the Enlightenment, the word “tourbillon” referred to a planetary system and its rotation around a single axis or to the energy that drives the planets’ rotation around the Sun.

As a man of the Enlightenment, Breguet named his complicated invention with science in mind, not in reference to a meteorological phenomenon. The tourbillon rotates orderly and irresistibly around a central axis, just like a planet in a galaxy. Breguet’s astronomical idea for a regulator rotating on its axis proved successful, as his tourbillon significantly improved the accuracy of timepieces.

To obtain a patent for his invention, Breguet had to submit a file containing an illustration and a letter to the Minister of the Interior; a bureaucratic nightmare in the best French tradition. In the letter, Breguet wrote: “I have the honor to present a dissertation describing a new invention for use with chronometric instruments. I call this device the Tourbillon Regulator […] By means of this invention, I have successfully compensated for the anomalies resulting from the different positions of the centers of gravity caused by the movement of the regulator.”

The patented tourbillon

Whether the minister fully understood all this is unknown. However, Breguet’s patent was approved and recorded on the 7th of Messidor, year IX, as it was on the French Republican calendar just after the Revolution. The exclusive right to produce the tourbillon was granted for 10 years, from 1801 to 1811. Considering the complexity of the invention, this was extremely short. This was also evident because producing the first Breguet pocket watch with a tourbillon took several years.

After two experimental models — watch no. 169, given to the son of John Arnold in 1809, and watch no. 282, completed in 1800 but sold by Breguet’s son much later — the first tourbillon pocket watch wouldn’t debut until 1805. The general public first saw the tourbillon at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products in Paris a year later. Breguet praised his tourbillon as a mechanism that allowed timepieces to “retain their precision whether upright or inclined.”

Between 1796 and 1829, Breguet and his associates constructed 40 tourbillons — plus nine other pieces that were never completed and are listed as written off, discarded, or lost. More than half of these creations have a cage that rotates once every four or six minutes. This is remarkable because Breguet’s patent describes a cage that rotates every minute.

Among the customers of his tourbillon creations are monarchs and aristocrats. It is also quite remarkable that a quarter of Breguet’s tourbillons were used for their intended purpose — to tell the time as accurately as possible. Marine navigators used pocket watches with tourbillon movements for navigation at sea and calculating longitude, and prominent scientists also benefited from the precision of Breguet’s invention in their research and experiments.

No diary, but plenty of inventions

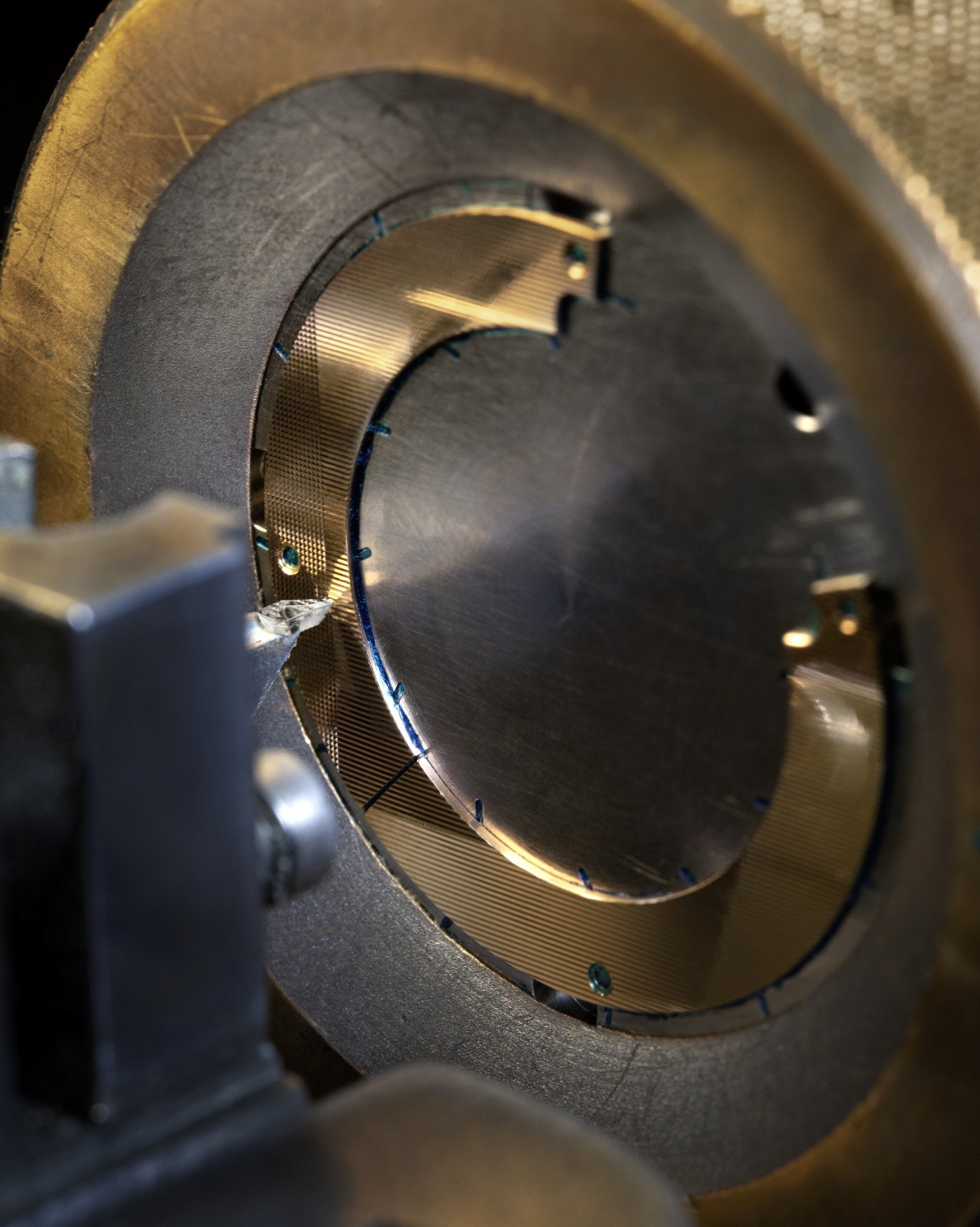

It’s hard to talk about the man Abraham-Louis Breguet because he didn’t leave a diary. Instead, he left a string of inventions. Some were technical, some aesthetic, and some a bit of both. The idea of adorning the dial of a pocket watch with an engraved geometric guilloché pattern came to him in 18th-century London. He saw furniture and ivory objects embellished with various guilloché patterns and decided to apply this technique to his watchmaking creations on a much smaller scale. The first Breguet pocket watch with a guilloché dial appeared in 1786, and many creations would follow.

For furniture, guilloché is no more than an aesthetic enhancement. But for an 18th-century pocket watch, it had practical uses. Abraham-Louis was faced with counterfeit Breguet pocket watches and devised ways to outsmart the counterfeiters. Applying a delicate guilloché pattern was reserved for highly skilled craftsmen and way too ambitious for counterfeiters looking to cash in on his name. Later, in 1795, Breguet also introduced the secret signature etched into the dial. The miniature signature only revealed itself after inspection under a magnifying glass.

Quarter repeater watch no. 168, guilloché gold case, platinum body, guilloché silver dial, blued steel Breguet hands, gold cuvette bearing the inscription “Given to Mr. Baron Albert de Pichon-Longeville by His Royal Highness the Duke of Angoulême, 1814”

A guilloché dial also has other practical functions besides outsmarting counterfeiters. The relief cleverly traps dust that might enter the pocket watch’s movement, making it a practical advantage. Also, a speck of dust in an engraved pattern, unlike on a flat, smooth, white dial, doesn’t stand out — an aesthetic advantage. An additional benefit of a guilloché dial compared to a plain, lacquered, or enameled one without relief is its readability. Because it reflects light less harshly and sharply, it is easier and faster to read.

Marketing genius Breguet

Abraham-Louis Breguet left France when it was a monarchy and returned to a republic. “The world had completely changed,” explains Emmanuel Breguet, a seventh-generation descendant. “His old customers were gone, and he had to earn money by building a new clientele. Now he returned to Paris to make affordable watches for a less affluent demographic, but with the quality of a Breguet. His Montre de souscription is a subscription watch. You subscribe, pay a portion, and you pay the remaining amount upon delivery, guaranteed by Breguet. This made Breguet watches more accessible, and the advance payments helped finance the development of other projects.”

The idea behind the Montre de souscription and its technical construction are equally fascinating. The ingenious subscription watch is reliable and accurate at a lower cost than usual at the time. To achieve this, Breguet designed a robustly constructed movement that inexperienced watchmakers could repair and maintain. Furthermore, it had to be produced in sufficient quantities to meet the high demand. A total of approximately 700 subscription watches were built and sold.

To reduce costs, Breguet used a single long and slender central hand over the spacious dial layout. The dial indicated the hours, half hours, and quarter hours, as well as 10- and five-minute intervals. The first subscription watch was sold to M. Coquille on the 11th of Germinal, year IV, the date according to the French Republican calendar. That’s April 1st, 1796, according to the Gregorian calendar. The movement’s architecture was crude in the early examples, but it gradually became more refined.

Today, the design of some souscription models lives on in the Tradition collection, and the recently introduced Classique Souscription 2025 is a contemporary wristwatch interpretation of the original single-handed models.

Another watch for a queen

In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte became the powerful First Consul, and in 1804, he crowned himself Emperor of France. The old regime was dead, buried, and forgotten, but Breguet and his reputation were not. The emperor and his first wife, Empress Josephine, became lucrative customers. And for the emperor’s sister, Caroline Maria Annunciata Bonaparte, Breguet created a world first. Emperor Napoleon ensured that his sister became Queen of Naples — then an independent empire — in 1808, when he crowned her husband, Joachim Murat, the second Napoleonic King.

For the Queen of Naples, Breguet created a wristwatch. It’s sufficiently documented to be crowned the “World’s First Wristwatch.” Unfortunately, a search for the original, small, and oval watch has been unsuccessful. Still, in 2002, the contemporary Reine de Naples debuted with a design based on archive drawings of the original creation.

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s last decade

Breguet was most definitely a social man. He networked with royal courts in many countries, for instance, and started the first-ever “Kickstarter campaign” after his return from exile. He also befriended many great watchmakers. Louis Moinet, who, later in his career, invented the chronograph, was one of them. Breguet recognized young Moinet’s talent immediately, and from 1811 onward, Moinet served him as his personal adviser. The two also collaborated on artistic and technical matters.

At the same time, Breguet’s reputation within the scientific world continued to rise. In 1814, he was appointed a member of the Bureau des Longitudes. And the following year, after the monarchy was restored, King Louis XVIII named him official chronometer maker to the French Royal Navy. His prestige grew further in 1816 when he was elected a full member of the French Academy of Sciences. Three years later, in 1819, Louis XVIII personally presented him with the rank of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

Breguet’s influence also reached beyond his generation. In 1822, the 16-year-old Isambard Kingdom Brunel, one of Britain’s most outstanding engineers, studied for several months in his Paris workshop. It’s not hard to imagine he benefited greatly from Breguet’s experience and innovative environment.

Who was Abraham-Louis Breguet? The man behind the name

Despite his many accomplishments, Breguet was remembered as much for his character as for his genius. Sir David Salomons, a renowned collector who owned 120 Breguet watches, including the extraordinary “Marie-Antoinette” watch, recounts in his 1921, 230-page study of Breguet, titled Breguet 1747–1823, that he often rewarded his craftsmen more generously than they expected. For example, if an invoice ended in a zero, he would extend the digit into a nine. He also encouraged his apprentices, always reminding them never to let failure weaken their determination. Breguet was indeed a modern manager and motivational speaker avant la lettre.

Abraham-Louis Breguet died in Paris on September 17th, 1823, leaving behind a thriving business and a legacy that reshaped horology. Today, the Breguet name lives on as a brand that is part of the Swatch Group, a conglomerate that includes brands like Omega, Longines, and Blancpain. Abraham-Louis Breguet was laid to rest in the 11th division of the Père-Lachaise cemetery. The grave is not easy to find, but it’s worth visiting if your heart beats for horology.