A Case For Future Watches: The Supercomplication Smartwatch

A smartwatch does quite a lot. From a watch enthusiast’s standpoint, however, it doesn’t do nearly enough. Sure, you can get watch faces that display the time in analog. But the similarity to an actual mechanical watch is akin to a child’s R/C car versus an actual car. Where are the gears? Where are the complications? In short, where is the horology? It may seem like such a technological device must forgo the mechanics of time for simple emulation by necessity. I’m here to say that smartwatch developers are missing a huge opportunity. The grandest one, even.

For all of its computing power, a smartwatch like the Apple “Watch” allocates very little of it to telling time. Sure, it displays the time and date perpetually, and one can use it for alarms and timers. But the time is delivered to the device from exterior sources, regardless of how closely the watch face emulates well-known watches. The alarms and chronographs don’t incite the same excitement a mechanical chronograph does, and good luck looking for further complications. You’re left with asking Siri if you want to know the phases of the moon, the equation of time, or whether it’s a leap year. That’s hardly a romantic way to marvel at time, especially if you have any experience interacting with Siri.

Replacing emulation with simulation

But it needn’t be that way. A Samsung Galaxy Watch5 employs an Exynos W920 computer chipset with a 1.18 GHz dual-core clock rate and 12 Gb of LPDDR4 memory. I can see the watch nerds’ eyes clouding over with these unfamiliar specs. Essentially, this places the computational power of a Samsung Galaxy Watch5 at double that of an iPhone 4. Coincidentally, the Cray-2 supercomputer from 1984 shared similar processing power to that of the iPhone 4. The Apollo guidance computer that put men on the Moon had the processing power of about double that of an original Nintendo NES. The NES’s clock rate was about one one-thousandth of the Galaxy Watch5, and the RAM was millions of times less at 2 Kb.

All this is to say: if NASA could get men on the Moon with 1/500th the processing power of a modern smartwatch, if a supercomputer from 1985 is similar in power to an iPhone 4, and if today’s smartwatches are twice as powerful as an iPhone 4, there’s no reason that what I’m about to propose can’t be possible.

Complicated computers? Meet complicated watches

The Henry Graves Supercomplication pocket watch took Patek Philippe three years to design and five years to build in the early 1900s. It featured 24 different watch complications and remained unchallenged for over 50 years. In 1989, the Patek Philippe Calibre 89 surpassed it with 33 complications. It remains the most complicated watch ever made without computer assistance.

Computer assistance made the Vacheron Constantin Reference 57260 possible. Reference 57260 was introduced in 2015 and features 57 complications. Some of these complications include both perpetual Gregorian and Hebrew calendars; seasons, equinoxes, and solstices; sunrise times, sunset times, and length of days and night for the owner’s home city; moon phases and age; a complex chronograph, an alarm and other chiming functions. The 57260 took eight years to make.

These supercomplication watches also happen to be incredibly expensive when they turn up for auction, fetching millions. This is because the incredible knowledge, skill, effort, and time that go into these watches resulted in one-of-a-kind pieces. But all of these complications fit inside the cases of pocket watches smaller in diameter than a teacup saucer. For all their complications, the three-dimensional space they inhabit is relatively small.

Put a watch in it

I had a few games on my iPhone 4 years ago. I enjoy racing games myself. The 3D racing games spanned tracks that were multiple virtual miles long with detailed scenery and vehicle details to make the experience as realistic as cell phone technology could deliver at the time. We had come a long way from 2D Mario Bros. on the Nintendo NES twenty-something years before.

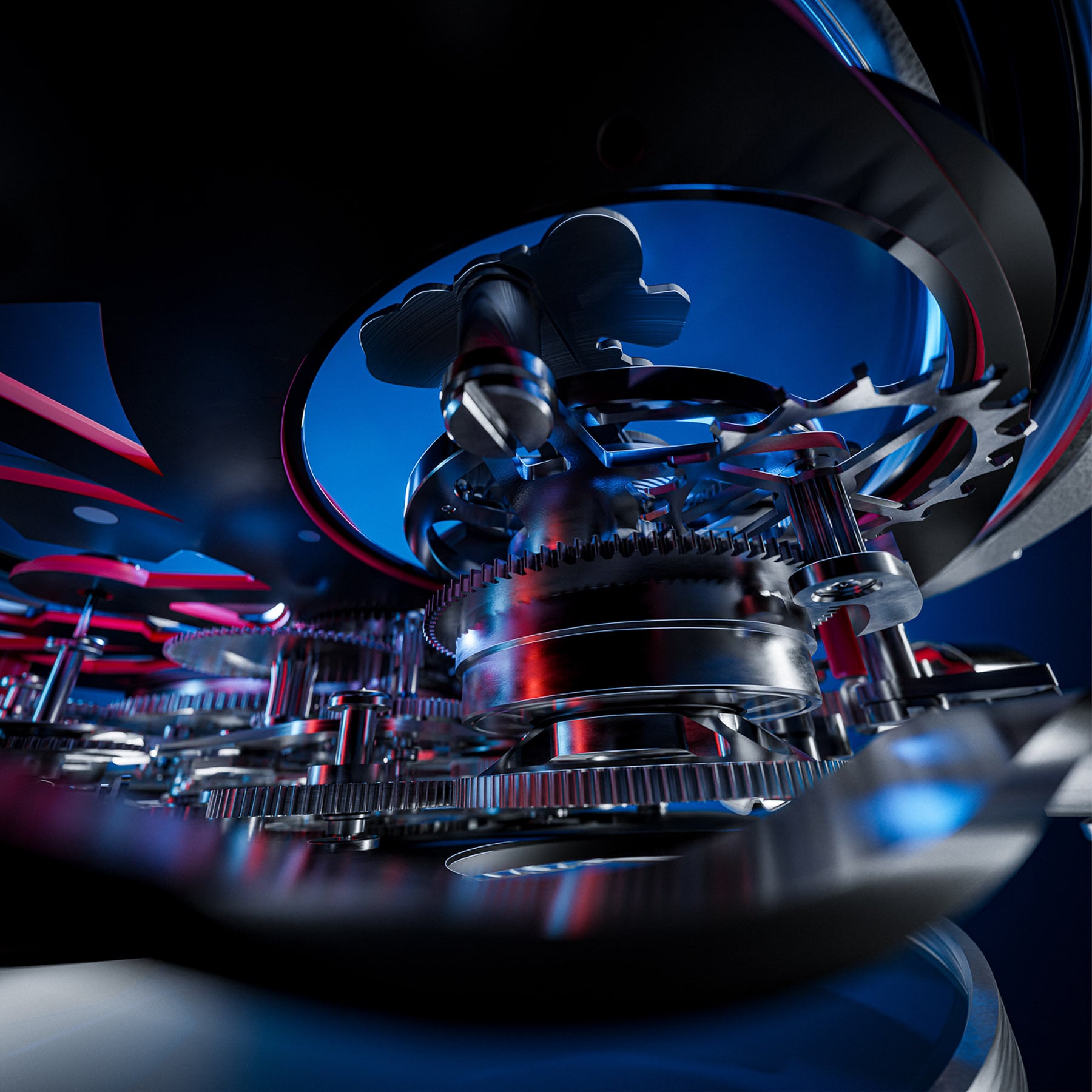

What would be possible if the same memory and graphics that went into the three-dimensional racing, shooting, and adventure games on our phones were put towards a program that simply contained an operating, virtual mechanical watch? Can you imagine what computational resources would be available to it?

A watch in a three-dimensional virtual space would not be constrained by the same pitfalls our real-world watches are subjected to. Gravity need not exist, nor does temperature, doing away with many of the headaches those two elements play on accuracy. But more importantly, construction would be a breeze compared to physically making a watch. In virtual space, a programmer can zoom in or out as much as necessary. Additionally, there’s no reason a virtual caliber would need to be constrained to a certain orientation or shape.

The (virtual) sky is the limit

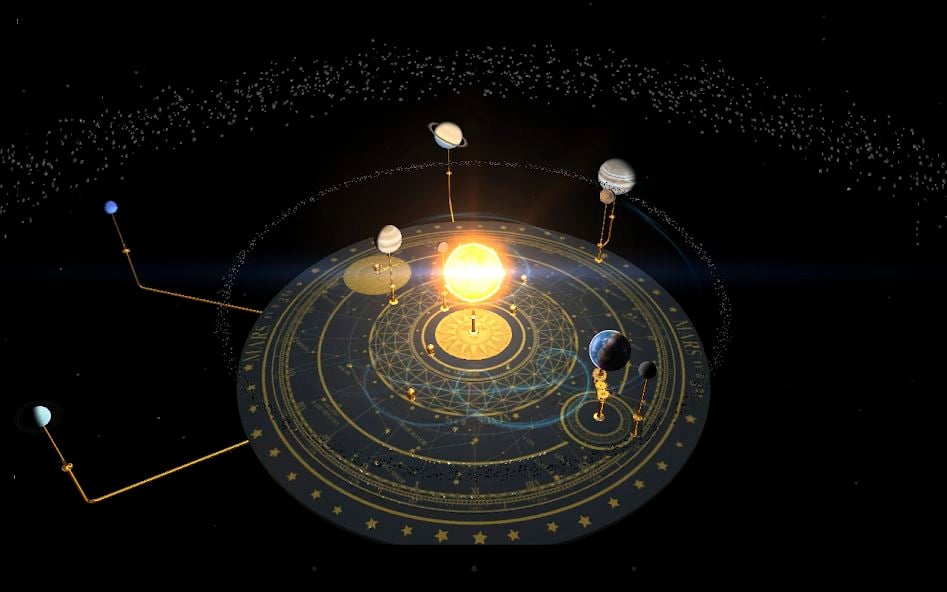

In fact, there’s no reason that programmers wouldn’t be able to take virtual watchmaking to heights similar to what we experience in the wild fantasies of video games. Complications wouldn’t need to stop at the terrestrial. Formulas and gearing could be incorporated to account for the progression of other planets and moons in our solar system. One could, in effect, have the most complex orrery within virtual space. Speaking of which, some programmers took it upon themselves to digitize an orrery as an Android app. It’s a very cool, interactive model of our solar system and a step toward simulated astrological mechanics for the sake of entertainment.

The universe on your wrist

Take all of that and throw it in a program and visual format that works as a smartphone app. One might not find the concept of what is essentially a video game of complicated watchmaking all that alluring on paper. But it is the lack of real horology and watchmaking that makes smartwatches so unappealing for many of us. I’m not suggesting it will make converts of all the analog-allied enthusiasts, but for the watch enthusiasts that must wear or have to like wearing a smartwatch, being able to experience time in a more traditional sense might make the experience more enjoyable.

I don’t believe the creation of the caliber would even be the most difficult aspect of design for a smartwatch-based supercomplication. I think, with the limited real estate, the biggest challenge would be determining how to best display the information. It couldn’t be too overwhelming; there’s only a small square screen to work with. Maybe the dials and hands could be separated onto various screens. In fact, if one were to put the virtual complication in a cube enclosure, one could essentially make each of the six faces of the cube a display face that the user could swipe through. On the two-dimensional display of the smartwatch screen, that might not look like much, but 3D has always been more fun.

Double the power, double the fun

Considering smartwatches are now already twice as powerful as the iPhone 4s from not that long ago, I see little reason why the three-dimensional space of the virtual watch caliber couldn’t be set up to be explored via the touch screen of the watch. If I was racing Porsches on my iPhone 4 in 2010, I don’t see why one couldn’t pinch, pull, and swipe their way through and around a virtual watch movement on a smartwatch in 2022. It would allow one to enjoy (virtual) watchmaking in a way not available to the real world, where one might zoom around and through gear chains, springs, and bridges.

Of course, such an interactive app might require a negotiation between OS providers and app developers. Most apps for smartwatches today operate as little more than widgets, doing and displaying the bare minimum to get the task done. But there are games available for smartwatches, and 3D-navigatable ones at that. It might not be all that much of a stretch to set such an interactive program as the default clock.

Ridiculous or necessary?

Most importantly, a virtual watch complication would wrest the command of time from the cold clutches of broadcast data and deliver it back into the rightful hands of gears, springs, and (watch) hands, virtual though they may be. Assuming the caliber is designed for utmost accuracy, the program wouldn’t even need to connect to the smartwatch’s time data. One could “set” the virtual watch as any other watch would be set and then run indefinitely in the background. Imagine the face of a stranger glancing over as you use your smartphone to manually set your virtual watch.

… it’s the severe practicality of smartwatches that causes many of us to spurn them. A little impracticality is exactly what smartwatches need to help bridge the gap between the computationally-digital tribe and those firmly rooted in anachronistic mechanics.

I understand that this sort of program wouldn’t be practical. That’s not what we’re here for. In fact, it’s the severe practicality of smartwatches that causes many of us to spurn them. A little impracticality is exactly what smartwatches need to help bridge the gap between the computationally-digital tribe and those firmly rooted in anachronistic mechanics. Watches are a lot like little poems. The sum equals more than its parts and meaning, emotions, and other ineffable qualities are transmitted through the experience. Nowadays, I read plenty of poems on a screen. I see no reason why the poetry of time couldn’t translate to some degree as well. But in the meantime, I’ll appreciate watch poetry in analog.

Would you wear one?

Is a smartwatch-based supercomplicated watch something you’d be interested in? Should the worlds remain separate and the purity of watchmaking not be sullied with such a disgraceful avatar? Let us know how you feel about such a concept in the comments below. We’re now through part two of the three-part “A Case For Future Watches” series. The first part was all about taking user interaction away from the physical watch. This part was all about putting user interaction into the digital watch. Stay tuned for the third part, coming soon, where I complete the trilogy of horological concepts that the future may or may not be ripe for.

You can find more of me on Instagram: @WatchingThomas