The Early Rolex And Tudor Oyster Watches That Saw Action In WWII During The Battle Of The Atlantic

Rolex is a hallowed name in horology. Yes, like me, you may be one of those who share in a widespread exasperation at waitlist games, the difficulty in attaining a new timepiece for non-VIPs who want one, and what the brand can represent to some in this age littered with vacuous social media influencers. Rolex is divisive, and we here at Fratello have written extensively on the Crown, from stories about modern marketing pitfalls to the evergreen appeal of a Rolex classic. Whether we feel love, anger, a sense of “meh,” or all of the above, we can’t seem to stop discussing Rolex. This is natural considering the enormous market share that Rolex and Tudor have.

For me, Rolex is not about the modern pitfalls. Rather, it’s about a brand steeped in rich history and good stories. For example, consider the Fratello saga of Australian surfer Matt Cuddihy finding a Rolex Submariner at the bottom of the ocean, which was later reunited with Ric, its owner of many decades. Or consider the humble Rolex field watch that served with Australian soldiers, the “Rats of Tobruk.” Something from the Rolex “stable” can speak to us enthusiasts, and this has nothing to do with Rolex being an “it” brand or investment. Rather, it’s because Rolex just makes good watches. I deeply appreciate Fratello Managing Editor Nacho’s taste for the Explorer II 16570, for example. You can read about that here.

Looking back to the 1940s

Therefore, this is not a story about modern Rolex or the problems with our consumerist (and frankly less romantic) world that modern Rolex in part reflects. This is a story about tiny, humble timepieces strapped to burly wrists, in turn, attached to human beings who helped save the Allies in the greatest conflict of the last century, the Second World War. These watches don’t even get to 36mm in case diameter, but they did participate in the longest continuous campaign of WWII.

As my colleague Brandon covered in this excellent article series, Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf was a key implementer of the notion of a waterproof watch case for the masses. This became known as the Oyster case. While others had already developed “waterproof” cases before Rolex, Hans Wilsdorf’s company was the first to turn them into a raging commercial success through the use of effective marketing. This included Wilsdorf equipping swimmer Mercedes Gleitze with a Rolex Oyster for her English Channel swim on October 21st, 1927. Fixed to a necklace around Gleitze’s neck, the watch was submerged in the frigid waters for over 10 hours and passed this endurance test with flying colors.

Already proven and ready for battle

Rolex was already a proven watch company by the onset of WWII. Throughout the 1930s, Rolex had been doing well globally thanks to its patented Oyster cases and perpetual rotor-wound movements. As my colleague Brandon notes in his history series of the brand, “As World War II progressed throughout the early 1940s, Wilsdorf found it difficult to export his watches from Switzerland, leading to a decline in sales worldwide. During this time, however, Rolex watches became popular with soldiers, who bought them to replace their standard-issue wristwatches.”

Soldiers did indeed appreciate these Oyster watches, so much so that the Royal Canadian Navy seems to have acquired Oyster-cased watches for naval officers in the early 1940s or, at the very least, that RCN officers bought them and had them engraved. In either case, there are some examples of engraved Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) Tudor Oysters. These watches usually had simply “Oyster” or “Oyster Raleigh” on the dial. In fact, we have reached out to the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation to see if there’s anything in the archives about them. If that search leads to anything, we will be sure to bring you that part of the story.

Mysterious naming conventions

The predominant theory is that these mysterious Rolex timepieces with different names emerged because, in the 1930s and 1940s, Rolex still had an agreement with Gruen to not sell Aegler-based watches in North America. This meant watches produced by the overarching Rolex company had some oblique branding in Canada to honor its agreement with Gruen, using names like “Oyster” and “Commander.” The watches were almost all 29–32mm in case size, many had the reference number 3478, and they had the Rolex/Tudor caliber 59 inside (a rebranded Fontainemelon caliber 30). One collector of these watches has managed to track down 21 different names (!) of these cross-branded watches. However, according to preliminary research, it seems that “Oyster” and “Oyster Raleigh” were particularly popular with Canadian servicemen.

This was not entirely unusual for the era because Tudor had not established itself as the clear “shield” for the Rolex crown yet. Hans Wilsdorf had been experimenting with other names, including “Unicorn.” Why not experiment in Canada, then? Names aside, these hardy watches from Rolex Watch Co. (RWC) ended up being very popular with Canadian naval officers. In this photo, what is clearly an Oyster-cased watch is on the wrist of none other than Vice-Admiral Rollo Mainguy, the commanding officer of the HMCS Ottawa, a C-Class Destroyer that served as a convoy escort and Submarine hunter in the Atlantic. Vessels like this saw fierce action, and the Ottawa (initially built in the UK as HMS Crusader) was lost to a German U-boat attack in 1942.

Serving at a time of global crisis

When Canada answered the call to aid its “motherland” as part of the British Commonwealth, it was not at all prepared for war. The Royal Canadian Navy had 13 vessels in 1939 when war broke out. But in a flurry of activity, the young nation managed to become part of the reason the Allies prevailed in WWII. It is no exaggeration that if the United Kingdom had lost the Battle of the Atlantic to the Axis, it would have been starved into submission. Winston Churchill knew he needed a large navy of escort ships that could tackle German U-boat “Wolf Packs,” hunting groups that were doing vast amounts of damage to British merchant shipping. The RCN (and the RCNVR by extension) was critical to this strategy.

During WWII, the RCNVR became the backbone of the Canadian Navy and recruited many of its officers and sailors. Largely thanks to the RCNVR’s efforts, Canada’s navy had nearly 100,000 members by 1945. The RCN had also become the fourth-largest fleet in the world — behind only those of the US, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union — with more than 400 warships (far more than the 13 it had at the start of the conflict). Although the RCN had no battleships or submarines, Canadian sailors served with distinction on both types of vessels in the Royal Navy. This was all a far cry from where Canada had started when war broke out in September 1939.

Formidable conditions

Having a waterproof watch would have been useful while serving on a small vessel in the Atlantic. Notorious for storms, huge waves, and even ice blizzards, the Atlantic is a fearsome environment. Indeed, a watch that could handle these conditions would have been quite attractive to sailors.

Rolex had widely marketed the Oyster case before the war as an answer to water ingress. For those serving on, for example, a small Flower-class corvette (essentially, a modified fishing trawler design with weapons for war), it was not uncommon to experience huge Atlantic swells sweeping over the sides of the ship. This was commonplace for other smaller vessels as well. Watches with Rolex Oyster cases, marketed as “waterproof,” were better for withstanding these moments of inundation than most.

A tale of sacrifice

The accounts of waves sweeping over vessels highlight a simple fact: most of the vessels that Canadian sailors served on were quite small, like destroyers, destroyer escorts, frigates, and corvettes. The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous campaign of WWII, lasting the full duration of the war in Europe (1939–1945). While the RCN sank or helped sink more than 30 U-boats, its losses were still considerable. The RCN lost 14 warships to enemy attacks and another eight to accidents at sea. Consequently, approximately 2,000 RCN sailors lost their lives.

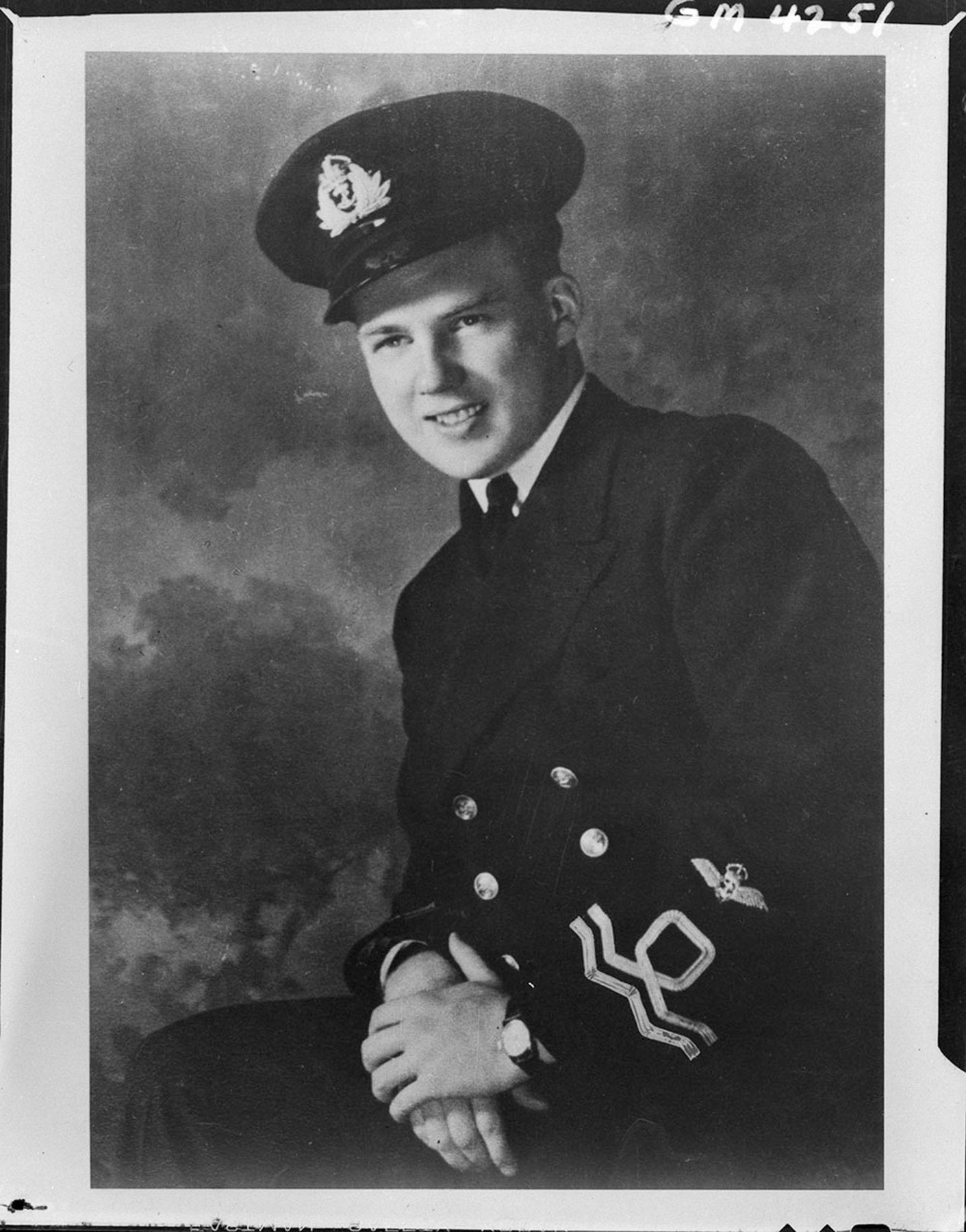

Canadians fought far and wide. One of those who lost his life in service of his country was Lt. Robert Hampton “Hammie” Gray, a member of the RCNVR from Nelson, British Columbia. He was a navy pilot with the British Pacific Fleet when he sank the Japanese corvette Amakusa on August 9th, 1945, an act which cost him his life.

The Pacific front

Lt. Gray, the only Corsair ace in the Royal Navy, had been leading two flights of Corsairs in the attack against Japanese naval ships. As he leveled out his aircraft for an attack run, it was blasted with heavy flak, cannon, and machine gun fire. The engine of the F4U Corsair, an enormous 2,000-horsepower 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial, would have been roaring.

His aircraft caught fire, and one of his 225kg bombs was shot off. Steadying his plane, he aimed the remaining bomb and hit the Amakusa, sinking it. A few seconds later, his burning plane hit the ocean at high speed, destroying it. Lt. Gray was one of the last Canadians to die in combat in WWII. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Apparently, the Canadian fighter pilot’s bravery so amazed the Japanese that he achieved an honor unique among Allied personnel: he was the only member of Allied forces to have received a memorial dedicated to him on Japanese home soil (erected in 1989).

A mysterious photo

Incredibly, in a portrait taken of Lt. Gray (two paragraphs above), he seems to be wearing an Oyster-cased watch. Fratelli, I would value your insights on this one, but the oversized crown and the lug design certainly look like those of an Oyster. This would stack up with how popular Oyster watches had become within the RCNVR, particularly among officers. We can’t know for sure, but it would be a fitting timepiece for the fighter ace.

Final thoughts

While researching for this article, I found it inspiring to learn more about the story of Canada’s brave sailors in WWII. As an Australian (Australia is a fellow Commonwealth nation), I always enjoy discovering more about this chapter of world history. It seems fitting that some of those who served wore a watch that stood the test of time. Whether these early Oyster-cased watches from Rolex were issued or just simply bought by Canadian sailors doesn’t matter too much to me. The fact is that they were there and used in some of the most difficult conditions that humans could face. It makes me happy to own a vintage (albeit 1960s) Oyster!

What do you think, dear Fratelli? It would be great to know more about these early Oysters. Let me know if there are any stories that you would like me to explore.