Audemars Piguet Has Reinvented The Chronograph: What Does It Mean To The Watch World?

Audemars Piguet is celebrating its 150th anniversary by introducing plenty of novelties, and they’re not watches. The brand from Le Brassus is also presenting new movements. The latest perpetual calendars now feature an ingenious crown, for instance, but the biggest news of the year is undoubtedly the launch of the Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5. This watch features the caliber 8100, a completely new take on the mechanical chronograph movement. The AP watchmakers did away with the age-old principle of the heart-shaped cam. It’s safe to say that Audemars Piguet has reinvented the chronograph with its new caliber 8100.

Before exploring the meaning of AP’s new chronograph caliber, let’s look at other landslide movement inventions and how they fared. The heart of your mechanical wristwatch is 350 years old. Dutch polymath Christian Huygens invented the modern oscillator by pairing a balance wheel with a hairspring. He put a very thin spiral in the heart of a clock movement’s regulating organ, and although the mechanism shrank over time, the principles remained the same. Even TAG Heuer’s new hairspring made in carbon follows Huygen’s invention, which proved to be a timeless success. His idea of a tiny, thin spring controlling the oscillation of a watch movement’s balance wheel led to more precise timekeeping and allowed miniaturization.

Audemars Piguet has reinvented the chronograph, but what other recent horological reinventions do we know of?

These days, there are balance springs made of special low-temperature coefficient alloys, like Swatch Group’s nickel-iron Nivarox, and Rolex has the Parachrom hairspring made of a special niobium-based alloy. Modern technology has also given us silicon hairsprings immune to magnetic fields. TAG Heuer thought creating one in carbon fiber would be a good idea. In 2019, the brand presented the prototype Carrera Calibre Heuer 02T Tourbillon with a carbon fiber hairspring. The same year, the Autavia Isograph collection with that hairspring debuted. Still, the technology faced setbacks and didn’t make its commercial debut until 2025, when the TH-Carbonspring appeared in new limited-edition Carrera and Monacao watches. TAG Heuer chose to stay on Huygen’s path, but some brands strayed from it, searching for even better escapements. Do you know which two brands I mean?

Escaping from convention

Girard-Perregaux and Frederique Constant invented the two revolutionary new escapements I’m referring to. Since Girard-Perregaux presented its new escapement first, we’ll start with that mechanism, which is based on a moving blade instead of a coiled spring.

The Constant Escapement employs a uniquely crafted and directly integrated silicium blade. In 2008, Girard-Perregaux created a prototype using silicon-based technology. This was possible thanks to the developments the brand made in collaboration with Sigatec in the ’90s, during what Girard-Perregaux describes as the advent of Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE). Upon its release in 2013, the Constant Escapement L.M. won the GPHG’s Aiguille d’Or.

Today’s Neo Constant Escapement is an evolutionary movement. One of its features is the incorporation of a fifth wheel within its gear train. This fifth wheel delivers energy to two escape wheels equipped with three teeth, operating in sync with the movement’s 3Hz frequency. The escape wheels alternate in transferring energy, ensuring a steady flow rather than a simultaneous release. This energy then passes through a rocking lever to the buckling silicon blade, which lies at the heart of the mechanism.

Six times thinner than a human hair

The Constant Escapement harnesses the blade’s “elastic and bi-stable” characteristics — despite being six times thinner than a human hair — to engage a lever that imparts a precise impulse to the balance wheel. Each oscillation comprises 20 sequences calibrated to deliver a constant force throughout the movement. This consistency maintains a uniform amplitude, ensuring precision. The symmetrical design of the blade and the escape wheels positioned on either side of the balance wheel further guarantees an even distribution of force to the regulating organ. The result is a smooth, balanced, and fluid rotational motion.

The movement featuring the Neo Constant Escapement isn’t in the 50th-anniversary Laureato that just came out, though. It’s only vibrating in a watch with the name of the regulating organ. The 45mm × 14.8mm titanium Neo Constant Escapement (ref. 93510-21-1930-5CX) has a price of €105,000 and is a very exclusive creation. The alternative escapement inside the hand-wound GP09200 caliber hasn’t trickled down to more affordable watches, and it doesn’t seem likely that it ever will.

Picking up fast vibrations

GP isn’t the only brand rethinking the escapement. In 2021, Frederique Constant presented a silicon oscillator beating at 288,000vph — yes, 288,000vph, not 28,800vph, equaling a 40Hz frequency, 10 times faster than the industry standard. The Monolithic escapement vibrates a stunning 80 times per second instead of eight. This is only possible due to a completely different concept that eschews a pulsating spiral and a swinging balance wheel.

The Monolithic escapement can move so unbelievably fast because of the silicon material used, the way it’s printed, and the amplitude. Expressed in degrees, amplitude is the distance a regulating organ moves from a position of rest to the position of maximum travel. A balance wheel’s optimum amplitude is around 300 degrees. FC’s silicon oscillator travels only six degrees from rest, a 50-fold reduction. The advantage is improved accuracy during general wear without sacrificing power reserve, which would be the case for a normal escapement operating so rapidly. It results in exceptional isochronous performance and an 80-hour power reserve.

The high-tech escapement debuted in the classically styled Slimline Monolithic Manufacture, a sub-€5k watch. People with deep knowledge of and interest in movements were in awe. Still, because manufacturing and regulation of the Monolithic caliber were complicated, at the end of 2023, FC stopped producing movements featuring the new escapement. It may make a comeback like TAG Heuer’s carbon hairspring, but there’s no sign of it yet.

What does Patek do?

Since AP operates at the very top of the Haute Horlogerie pyramid, it’s interesting to see what the direct competition is doing to advance mechanical watchmaking. For instance, in 2005, Patek Philippe established its Advanced Research department, which is now part of the Research and Development division. The department is dedicated to pioneering research in new materials, technologies, and design principles. The goal is to explore new possibilities and perspectives in watchmaking.

Six “Advanced Research” watches have debuted so far. Much focus went into the use of silicon, and the latest creation was the 2021 “Advanced Research” Fortissimo ref. 5750P-001. This minute repeater features a mechanical sound-amplification system for a much higher volume than traditional minute repeaters and good acoustic quality regardless of the case material. The “Advanced Research” watches are like rolling prototypes, mules that test new technology in real-life conditions. Over time, the technology trickles down into production watches. Still, Patek is on the gradual path of evolution, and AP is trying to start a revolution with its caliber 8100.

Reinventing the chronograph with the remarkable caliber 8100

Audemars Piguet also worked on minute repeaters. The RD series started with the Royal Oak Concept RD#1 Acoustic Research, a watch that resulted from the R&D team focusing on water resistance, volume, purity, and harmony of sound. The watches housing the caliber 3132, which features a double escapement, are not in the RD series. Unlike the escapements from GP and FC, AP’s open-worked caliber 3132 features two swinging balance wheels and traditionally coiled hairsprings. However, one sits on top of the other on a shared axis, all in the name of accuracy. Today’s caliber 8100 doesn’t feature a completely different escapement, although it does have a flying tourbillon spinning it around once every minute. Instead, the movement shows AP’s quest for intuitive simplicity.

The first expression was the gearbox-like crown of the Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar models in steel and 18K sand gold that debuted earlier this year. The one-crown-to-do-it-all approach makes adjusting a perpetual calendar movement easier and removes the fear of breaking the delicate movement. Caliber 8100 makes operating the chronograph softer and more subtle than ever because of a completely reworked system.

Effortlessly starting a revolutionary chronograph

AP’s Research & Development department spent five years developing the caliber 8100 for the Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5 (ref. 26545XT.OO.1240XT.01 / CHF 260,000), the final watch in the RD series. The chronograph function of the automatic movement features a flyback function and minute and hour counters with rare instant-jumping hands. There’s also a flying tourbillon for good measure. The idea behind the innovative construction of the new caliber 8100 came to Giulio Papi, the director of watchmaking design at AP and a living legend when it comes to creating complicated timepieces, during the coronavirus lockdown. He had little to do but fiddle with his smartphone. That this device would serve as inspiration for a groundbreaking mechanical watch is almost unbelievable, but the result proves it can be done.

The side buttons on a smartphone, used to turn the device off — who still does that these days? — require only a light touch. Activating a chronograph requires considerably more force. Papi was captivated by the difference. “When you press the pusher on a chronograph, you move it approximately one millimeter with a force of 1.5 kilograms,” Papi explained during an embargoed unveiling of the new creation this spring. “The goal was to reduce the pusher’s travel to 0.3 millimeters, requiring only 300 grams of force, just like with a smartphone.”

Minimal energy

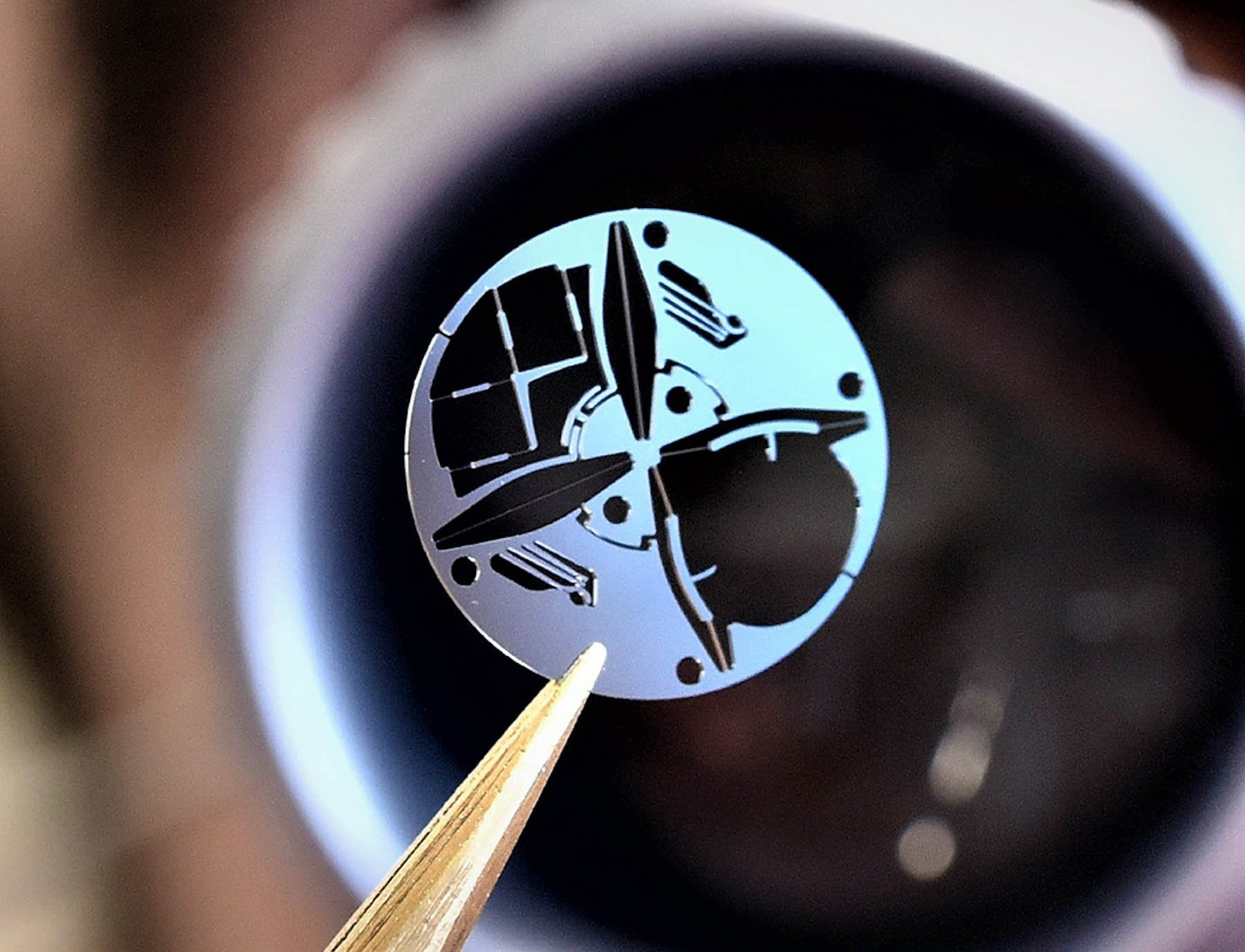

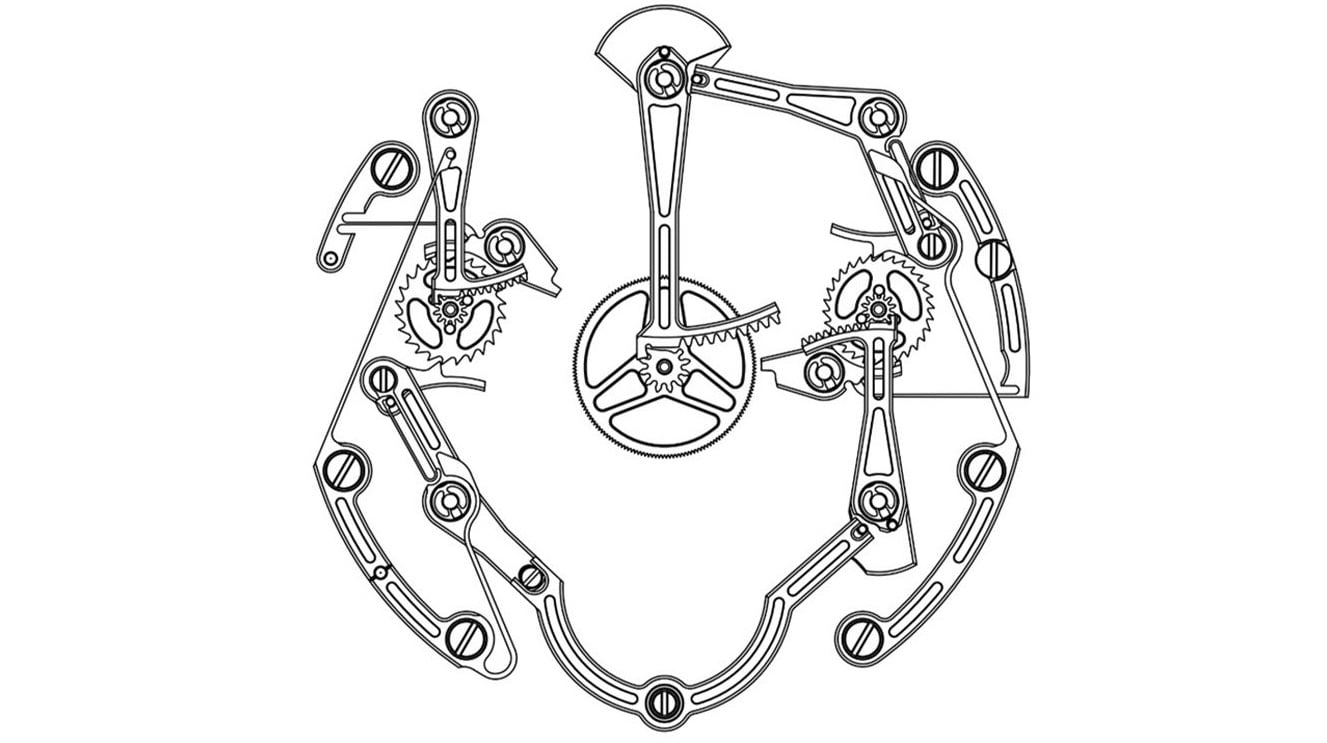

The development took a long time since an innovative rack-and-pinion mechanism replaced the traditional construction based on a heart-shaped cam and hammer. The new patented mechanism stores energy in the rack and keeps it under tension, preventing the chronograph hand from vibrating. Also, a friction spring, a component that acts as a constant brake when operating and resetting modern chronographs, is no longer necessary. The result is comparable energy consumption, but the energy, a rare and therefore cherished commodity in a mechanical movement, is now stored instead of dissipated.

Resetting a chronograph also requires energy, and AP’s watchmakers have also addressed this aspect. The goal was to achieve a smoother reset with less inertia. Once again, a press of the pusher releases the energy stored in the rack, causing the chronograph’s seconds hand to return to zero in a retrograde motion. Making the hand and various other movement components from lightweight titanium makes the reset instantaneous and consumes minimal energy.

Look, Mom, no brakes!

Chief Industrial Officer Lucas Raggi vividly explains how this movement works: “Think of a traditional chronograph as a car driving with the handbrake on. Caliber 8100 doesn’t have a handbrake. Instead of a handbrake, the car is now attached to a rubber band when it leaves the garage. This rubber band is then used to propel it back to the garage. The energy previously lost to the friction of the handbrake is now stored in the rubber band, or our patented rack-and-pinion mechanism. When the chronograph resets, the stored energy is released, and the hand returns to its position in less than 0.15 seconds. A lot of work has gone into understanding the behavior of the hands, so the reset is almost imperceptible to the eye.”

Other highlights of this movement are the crown with a function setting that integrates two modes via a pusher, an innovative vertical clutch system designed to start, stop, and reset smoothly, and the peripheral rotor. The Haute Horlogerie finish of the geometrical-looking movement is an aesthetic bonus. It includes carefully beveled chronograph bridges with a satin finish. The 379-part movement fits into a traditional 39mm “Jumbo” case, indicating its compact dimensions. It is exceptionally compact and thin, with a 31.4mm diameter and a mere 4mm thickness. A power reserve of 72 hours is also exceptional for a complicated movement of this size.

Why not?

A revolutionary new chronograph movement alone wasn’t enough to celebrate AP’s 150th anniversary. A tourbillon also became part of the mechanical celebration. When asked why a perhaps too-conspicuous tourbillon was added to the movement, Giulio Papi answered soberly, “The new chronograph mechanism requires fewer parts to function and takes up less space than a traditional construction. We had room left over for a tourbillon, so we thought, ‘Why not?’”

Who cares?

The question that points out the elephant in the room is: “Who cares?” Who cares about inventions in the parallel universe of mechanical watchmaking? Since this universe now thrives on image, storytelling, prestige, and other hard-to-quantify qualities rather than instrumental functionality needed in the real world, people care because they want to care, not because they need to. Also, mechanical evolution or even revolution is perceived subjectively, not objectively. Not many people answered the call when Frederique Constant tried to unleash a revolution. Why was that? Possibly, FC’s reputation was not prestigious enough. Unfortunately, sometimes, if you don’t have the name, you don’t get the appreciation and attention you deserve.

GP’s Neo Constant Escapement is also a lone warrior trying to stand out. The fast-moving blade inside its escapement was once announced as a new wonder of the watch world, but it never managed to conquer it. If the technology were easier and cheaper to produce, it would have made sense to see a string of GP creations in the current collection. But we don’t see different references outfitted with the silicium blade instead of a traditionally shaped balance spring.

On and underneath the dial

But, again, who cares? People are into watches, not watchmaking. It’s not about the outstanding revolutionary mechanics underneath the dial; it’s about the name on the dial. However, Audermars Piguet is a prestigious name in Haute Horlogerie and one of the most relevant brands. If AP decides not to limit the caliber 8100 to the 150 examples of the Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5 but starts producing sufficient quantities of this movement, it may find its way to more attainable Royal Oaks and Royal Oak Offshores. Then, the simplified, ultra-smooth, smartphone-inspired chronograph will possibly be a real game-changer.

The name on the dial impresses the wearer’s peers, while the tech underneath impresses the competing watch brands. Patents safeguard copying of the elements that make the caliber 8100 a revolutionary movement unique to AP. The Royal Oak’s status, charisma, and desirability, combined with a simplified and, thus, steadily producible caliber like no other, could make for a perfect storm. Not to mention, the chronograph is the world’s most popular and sought-after complication.

What are your thoughts on innovations in the field of mechanical movements? Do you find new technologies and creative approaches to existing complications impressive, or do they not interest you? Please let me know in the comments section.