A Close Look At The Omega Speedmaster Alaska Project — An Apex Predator Among Space-Dwelling Chronographs

The story of the Omega Speedmaster and the enigmatic Alaska Project begins not with the Moon landing but seven years earlier, long before Neil Armstrong uttered his legendary “one small step” phrase. In 1962, during the Mercury-Atlas 8 mission, astronaut Wally Schirra found himself orbiting Earth with his Omega Speedmaster 2998 strapped to his wrist. Following the successful splashdown, at a time when mass media was flooded with photographs of astronauts and rockets, one image from Schirra’s mission made its way across the Atlantic and onto the desks of Omega executives in Switzerland — Schirra, suspended in weightlessness, wearing his Speedmaster.

Until that moment, no one in Biel truly realized that this chronograph, originally engineered for timing events (of all sorts), had already left Earth and proven itself in the harsh environment of space. Once they did, the Omega execs reacted immediately and with purpose.

Ed White wearing his two Speedmaster 105.003 watches — Image: NASA

NASA needs a watch

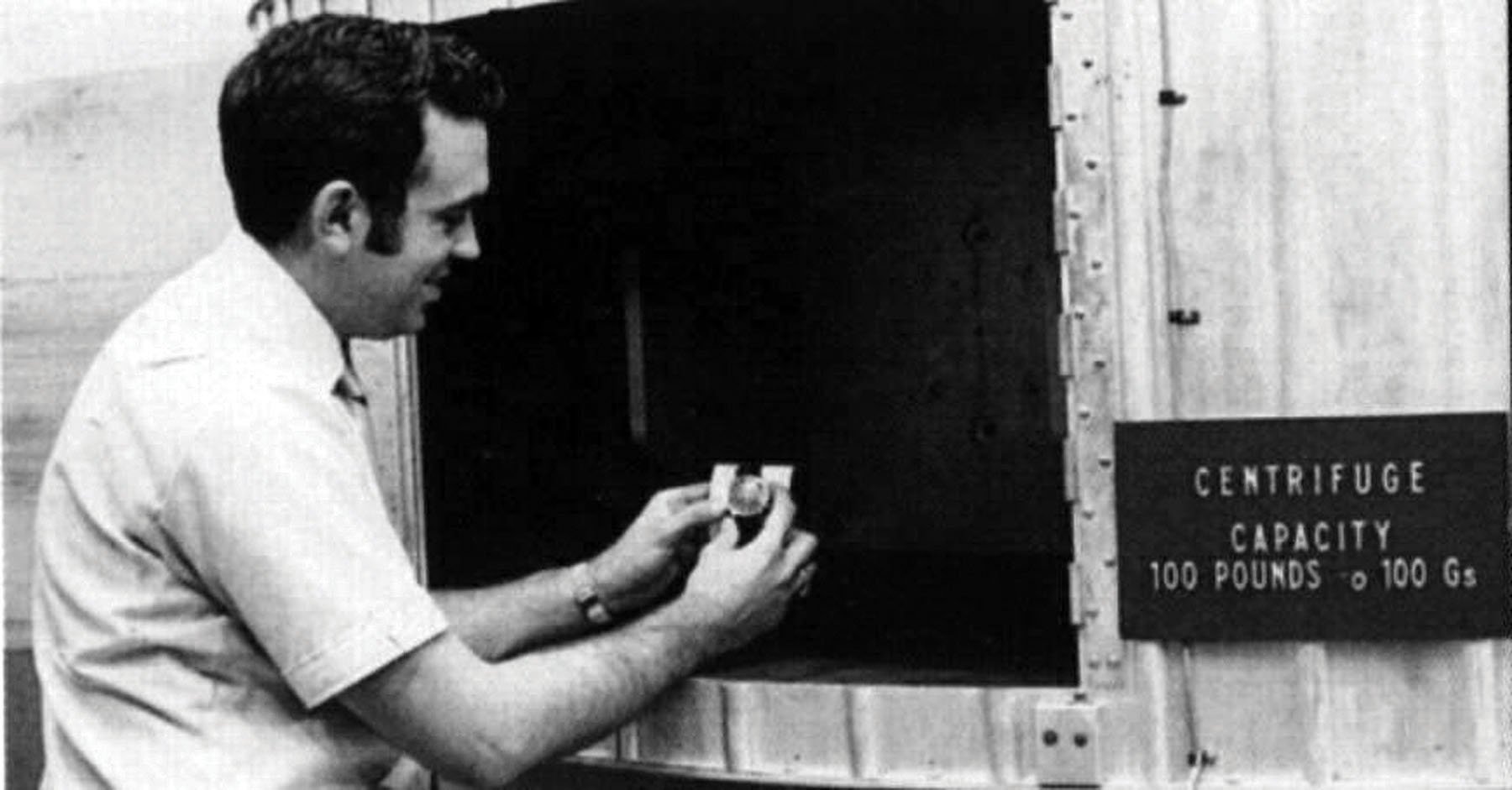

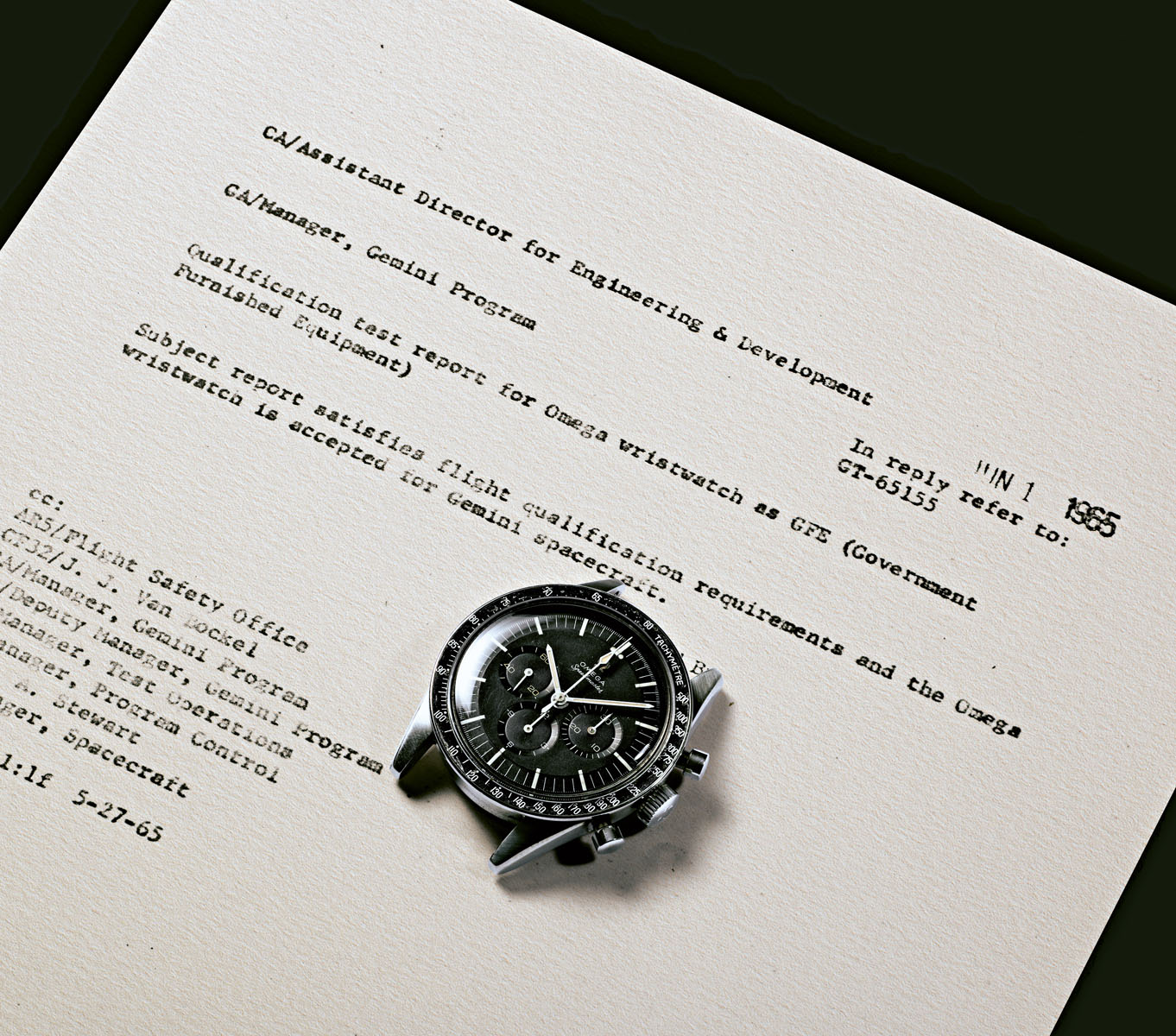

By 1964, Omega, Rolex, and Longines-Wittnauer had become the three remaining brands whose chronographs would undergo NASA’s notoriously brutal qualification program (we wrote about the three watches in detail here). To earn the coveted status “Flight-qualified by NASA for all manned space missions,” each watch had to survive a sequence of extreme, punishing tests designed to simulate the absolute worst conditions a timepiece might encounter in spaceflight. NASA devised 11 separate trials.

Achieving NASA spec

- High-temperature test: 70 °C for 48 hours and then 93 °C for 30 minutes in a partial vacuum.

- Low-temperature test: -18 °C for four hours.

- Vacuum test: heated in a vacuum chamber and cooled to -18 °C for several cycles.

- Humidity test: ten 24-hour cycles in >95% humidity with temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 70 °C.

- Corrosion test: an atmosphere of oxygen at 70 °C for 48 hours.

- Shock-resistance test: six shocks at 40 g in six different directions.

- Acceleration test: progressive acceleration to 7.25 g for about five minutes and then to 16 g for 30 seconds on three axes.

- Low-pressure test: pressure of 10.6 atmospheres at 70 °C for 90 minutes and then at 93 °C for 30 minutes.

- High-pressure test: air pressure of 1.6 atmospheres for 60 minutes.

- Vibration test: random vibrations on three axes between five and 2,000 Hz with an acceleration of 8.8 g.

- Sound test: 130 decibels at frequencies from 40 to 10,000 Hz for 30 minutes.

Passing this gauntlet meant that the watch could theoretically survive forces up to five times greater than those encountered during the most extreme emergency scenarios in crewed spaceflight, such as a ballistic emergency reentry of a Soyuz capsule. In the end, only one watch emerged victorious — the Omega Speedmaster ref. 105.003. It became the sole chronograph to pass NASA’s torture program without compromise, earning full flight qualification and cementing its role as the official watch for Gemini and Apollo astronauts. On June 1st, 1965, the Speedmaster received the official qualification to be used in space during EVA.

Flight-qualified

The 1968 launch of Apollo 7 marked NASA’s transition from near-Earth orbital missions to the bold lunar program that would eventually culminate in the first Moon landing. And with that transition came a host of new technical challenges. For example, during the roughly four-day journey covering approximately 386,000 kilometers to the Moon, the exterior of the spacecraft could heat to nearly 200 °C on the sunlit side, while dropping to -148 °C on the dark side. A thermal differential approaching 350 °C created enormous structural stress on the capsule’s outer shell and its sensitive onboard equipment. To combat this, engineers implemented what became known as Passive Thermal Control — more colloquially, the “barbecue roll.” Picture a rotisserie spit turning slowly over a flame. The spacecraft gently rotated along its central axis to distribute heat evenly across its surface, preventing catastrophic thermal concentration.

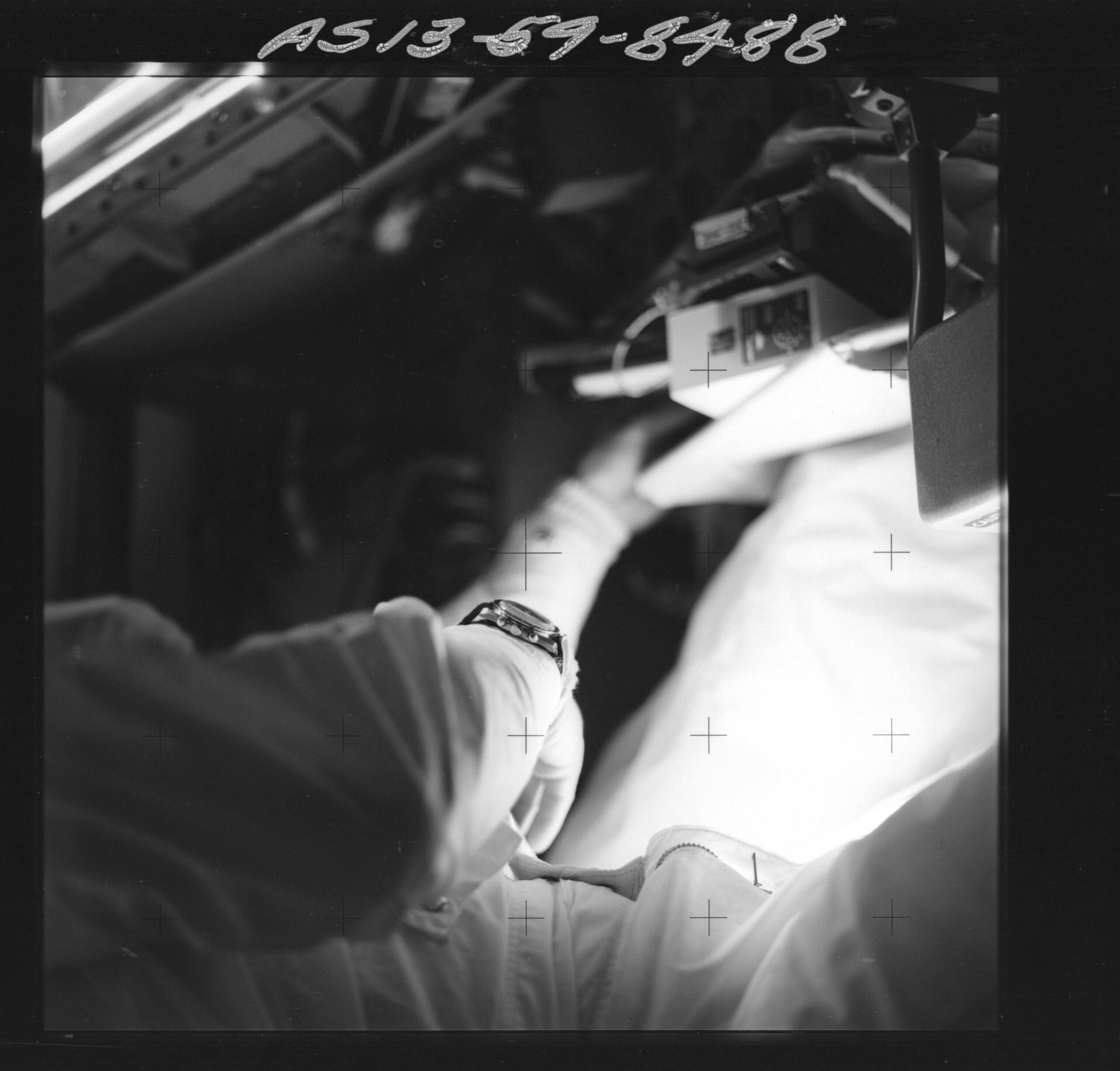

By this stage, the Omega Speedmaster had already secured its position as NASA’s official EVA (Extra Vehicular Activity) watch, and Omega quietly began developing a successor — a specialized instrument designed exclusively for NASA’s future missions, capable of correcting every shortcoming identified in the existing Speedmaster. This covert initiative received the code name Alaska Project.

The Speedmaster Alaska Project

The “Alaska” name had nothing to do with the US state. Instead, Omega deliberately chose the misleading code name to throw off competing brands and obscure the project’s true purpose. The initial prototype, Alaska I (ref. 5-003), emerged in 1969. Fascinatingly, it was not technically a Speedmaster in terms of case design, nor did it even bear the name, but it shared the same beating heart — the legendary caliber 861.

The Speedmaster DNA was still recognizable through its triple-register chronograph layout and baton-style hands. However, the case was radically different. Crafted from titanium, it had an asymmetrical cushion shape, a 44mm diameter, curved pushers, and a deeply recessed crown that stayed shielded from impact when not in use. Instead of a tachymeter bezel, which was useless in space, the Alaska I employed an internal chapter ring with fine subdivisions for high-precision timing. The chronograph hands were rendered in bright red, while the sub-dial hands were sculpted in the silhouette of the Mercury and Gemini capsules. This was a functional decision reflecting astronaut demands for maximum legibility under poor-visibility conditions, not a mere stylistic flourish.

A truly specialized Speedmaster

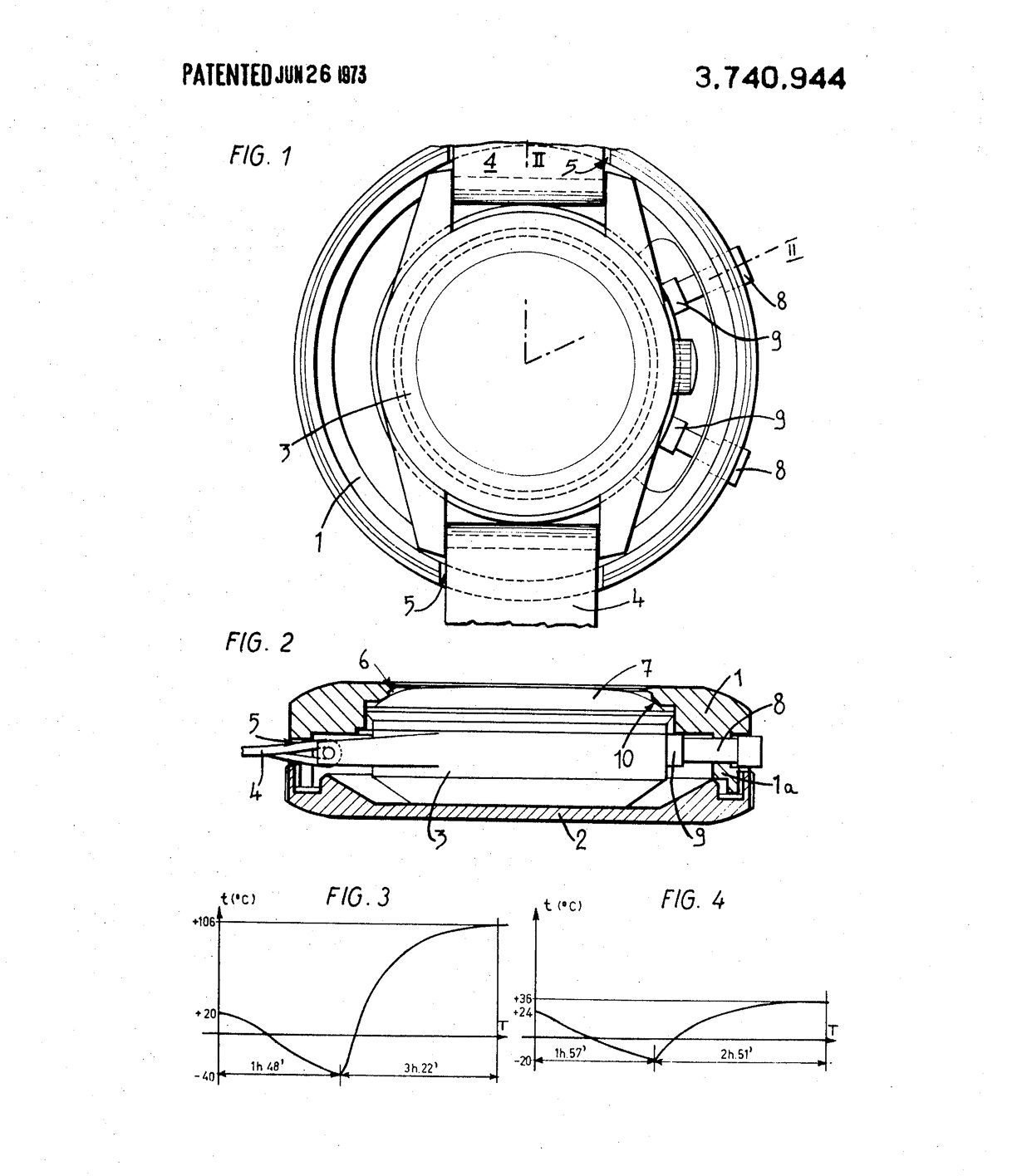

The most striking and technically significant feature of the Alaska I was its protective thermal housing — a removable heat-shield capsule constructed from anodized aluminum. Its purpose was to moderate extreme temperatures in vacuum conditions, providing the watch with a thermal buffer similar to the spacecraft’s barbecue roll. Omega’s patent US3740944A states that when the watch is left unprotected, its temperature could climb from 40 °C to 106 °C within three hours and 22 minutes of solar exposure.

Protected inside the housing, however, the temperature would reach only 36 °C (starting from 20 °C) within two hours and 51 minutes. To facilitate gloved EVA operation, the outer housing featured oversized pushers designed specifically for astronauts wearing thick extravehicular gloves. Since the dial could not be physically shielded, it was coated with zinc oxide, a reflective, heat-dispersing compound that provided an additional barrier against solar radiation and overheating.

Alaska Project patent

Alaska II

In 1972, Omega introduced the Alaska II. Speedmaster enthusiasts will instantly recognize its visual kinship with today’s Moonwatch models. This return to the classic shape was driven not by romance but by economics: manufacturing the titanium case of the Alaska I was prohibitively expensive. While the Alaska II preserved the traditional Moonwatch silhouette, it incorporated mission-oriented refinements. The case bore a fully bead-blasted finish to minimize reflections, since highly polished surfaces could reflect harmful solar rays in space.

The sub-dial scales adopted a radial layout for greater clarity, and early prototypes even featured a rotating bezel, which was far more practical in space than a fixed tachymeter scale. For the first time, the designation “Speedmaster Professional” was used on the dial of an Alaska Project watch.

Sadly, 1972 was also the last year the Alaska Project existed as an active development program. Costs were high, production was complex, and public enthusiasm for deep-space exploration waned sharply after the triumphant 1969 Moon landing. The prototypes never entered full production, but the legend endured.

Although the Speedmaster Alaska Project never made it into any of the NASA missions, it saw action on the wrists of Soviet cosmonauts from 1977 to 1981. According to Philip Corneille, who covered it in an article for SpaceFlight magazine in 2018, “Soyuz 25 cosmonauts Vladimir Kovalyonok and Valeri Ryumin wore Alaska II Speedmasters with red outer cases on the left forearms of their Sokol spacesuits.” You can find it in our article here.

October 9th, 1977 — Soyuz 25 cosmonauts Vladimir Kovalyonok and Valeri Ruymin — Image: MoonwatchUniverse

Later, in 1978, the Alaska Project II was also on the wrists of cosmonauts Vladimir Kovalyonok and Aleksandr Ivanchenkov during EVA. So, in the end, Omega’s specially developed Alaska Project made it to space.

A civilian-spec Alaska Project Speedy

In 2008, Omega finally unveiled a civilian version of the Alaska Project in a limited series of 1,970 pieces. The Speedmaster Alaska Project honored both the Alaska I and Alaska II in almost every respect. The dial retained the traditional Speedmaster arrangement but abandoned applied indexes in favor of luminous markers. Red remained exclusively on the main chronograph hand, a brilliantly restrained design choice, while the sub-dial hands once again evoked the silhouette of NASA capsules.

Beneath the case back, the iconic caliber 861 of the original 1970 Alaska Project was replaced with the updated caliber 1861. Mechanically, it remained the same reliable, robust, and proven Omega movement, with only minor refinements — a shift from bronze to rhodium-plated finishing, the change from a metal to a Delrin brake, and tweaks in jewel count. The most visually dramatic throwback was the return of the thermal shield, now a more user-friendly accessory included in the kit. While it might look like something straight out of a Halloween costume, it remains one of the most fascinating watch accessories ever included with a production Speedmaster, and an irresistible conversation starter for anyone who knows the model’s backstory.

Thoughts on the Alaska Speedmaster

From a personal standpoint, I’m probably one of the most biased people to evaluate Speedmasters. There’s hardly a version I genuinely dislike (with the notable exception of the Apollo XVII 40th Anniversary). Still, wearing the Alaska Project is a unique pleasure. It feels like a Speedmaster, yet looks like nothing else in the lineup. When it debuted in 2008, it wasn’t met with the enthusiasm it enjoys today; it often sat in display windows longer than expected, priced only slightly above the standard Moonwatch.

I vividly recall the market in 2013 while hunting for my first Speedmaster; both the regular Moonwatch and the Alaska Project were hovering around €3,000 on the secondary market for a full set. Today, the narrative has flipped entirely: the Alaska Project routinely surpasses €15,000, with mint examples commanding significantly higher prices.

Wearing the Speedmaster Alaska Project

On the wrist, the Alaska Project wears exactly like a Speedmaster Professional, with the same footprint and ergonomics, but the dial transforms the experience. On paper, a white dial with black hands should deliver perfect contrast and superb legibility; in reality, once the Sun begins to dip below the horizon, the classic black-dial Moonwatch pulls ahead.

Curiously, although the lume formula is the same, the Super-LumiNova on white appears brighter, likely because the green glow contrasts more sharply with the bright background. Strap versatility, however, is where the Alaska Project encounters its limitations. The Speedmaster Professional is famously a “strap monster, ” capable of pairing with virtually any material or color — steel, rubber, leather, NATO, canvas, you name it.

One might assume that the combination of white and red would be even more flexible, but in practice, it is surprisingly restrictive. Neutral tones — black, gray, navy — look exceptional, emphasizing the technical nature of the watch, while warmer hues like light brown tend to clash and diminish the aesthetic harmony.

Final thoughts

Despite these quirks, the Alaska Project remains one of the most original and compelling Speedmasters ever created, boasting a backstory that is rich and captivating enough to intrigue even the most discerning watch enthusiast. With its thermal shield, its NASA-inspired design, and the included NATO straps made from materials reminiscent of astronaut suit fabrics, the complete set is more than justified in its cult status. And if I had to choose just one chronograph to accompany my black vulgaris Omega Speedmaster Professional, there’s no question that it would be the Alaska Project.

You can read a previously published story on the Alaska Project watches (including the Alaska Project III and IV models) here.

Special thanks to Zvonimir Svalina for the story. You can follow him on Instagram here: @portalsatova