Water Resistance In Watches — Why “30m” Doesn’t Always Mean The Same Thing

If you’ve spent any time looking at case backs, you’ll have noticed the little engravings —“30m,” “50m,” “100m,” and so on. On the surface, it feels straightforward: “30m” should mean you can dive down to 30 meters, right?

Unfortunately, no, it definitely does not. But ask one brand, and it will advise you that “30m” is fine for handwashing and splashes. Ask another, and it will assure you it’s good for surface-level swimming. So, what’s going on here? Why does “30m” not mean the same thing across the industry? Let’s take a closer look!

Water resistance — Where the numbers come from

Water resistance ratings are based on static pressure tests, usually expressed in bars, atmospheres (atm), or meters. A “30m” or “3atm/bar” rating means the watch has been tested against the pressure you’d find at 30 meters below the surface. But that’s only in a controlled lab environment — no movement, no temperature fluctuations, no sudden pressure surges.

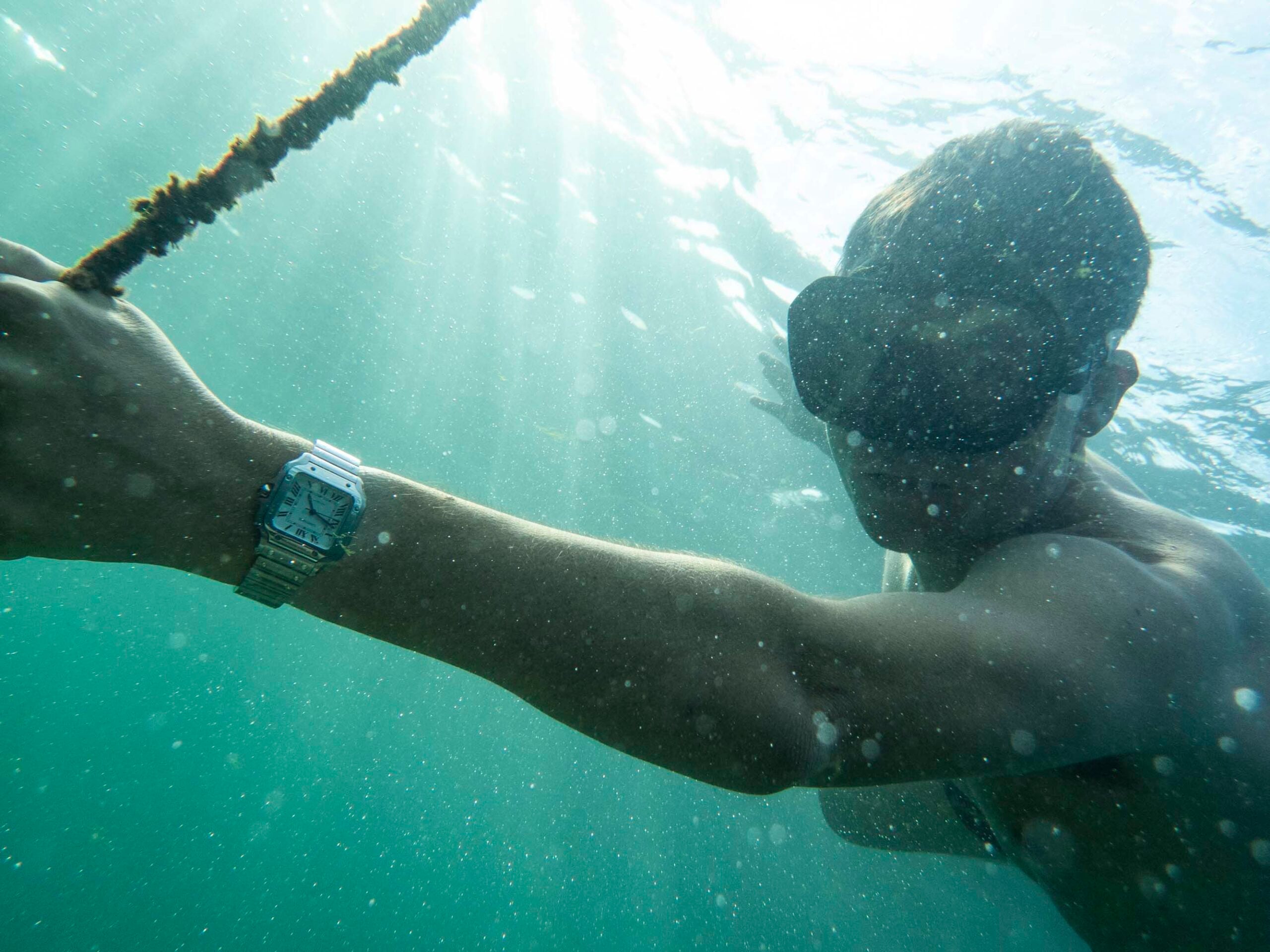

Real life is messier. Swinging your arm into a swimming pool, a wave hitting your wrist, or stepping from a hot shower into cool air can create pressure spikes that exceed the test parameters. That’s why the number on the back isn’t a literal guarantee you can take your watch to that depth.

Dry tests, wet tests, and safety margins

The testing methods themselves also differ. Dry (air) tests measure case deformation under vacuum or pressure. They’re quick, clean, and precise. Wet tests immerse the watch in water and check for leaks, often after applying air pressure. Both have merits, but they don’t always reveal the same vulnerabilities. Add to this the fact that some brands build in generous safety margins — testing well above the stated rating — while others stick strictly to the nominal figures, and suddenly, “30m” isn’t a universal term anymore.

So why does one brand say “splash only” while another says “swim away”? This is where communication style becomes just as important as engineering. Some companies are conservative in their guidance to avoid warranty claims (“30m = rain only”). Others, confident in stricter testing or better gasket systems, will say that the same number is fine for swimming. The result? Two watches, both marked “30m,” might live very different lives on your wrist.

IWC Schaffhausen — A case in point

IWC handles this problem in an unusually transparent way. Rather than sticking with the potentially misleading “meters” convention, the brand lists water resistance in bars. More importantly, IWC explicitly warns that these ratings are not literal dive depths. On its website, the company explains that meters “cannot be equated with dive depth because of the test procedures that are frequently used.”

“The following are some examples for explanation: an IWC watch with an indicated water resistance of 1 bar is protected against splashing water. With water resistance of 3 to 5 bar, the watch can be worn when swimming or skiing, and at 6 to 12 bar, it will have no problem with water sports or snorkeling. Diver’s watches with an indicated water resistance of 12 bar are professional measuring instruments designed for scuba diving. Special diver’s watches resistant to 100 bar or 200 bar are suitable even for deep-sea diving.”

In practice, this means IWC gives you both the number and clear guidance. This clarity sets IWC apart. Rather than leaving the consumer to interpret “30m,” the brand maps the rating to real-world scenarios.

Other approaches

Not all brands take this tack. Rolex, for example, is famous for in-house torture testing and for rating its cases conservatively. A 300m-rated Submariner is tested to greater pressures in the lab. Omega, with its Seamaster line, similarly exceeds ISO standards and tests to an additional margin of error.

At the other end of the spectrum, you’ll find makers of dress watches that do the minimum required and then hedge their messaging; “30m” here really does mean “keep it away from water unless you’re caught in the rain.” The inconsistency isn’t because anyone is cutting corners — it’s because testing philosophies, marketing strategies, and risk tolerance differ.

What this means and a simple cheat sheet

So, how should you read those numbers on the case back? A few rules of thumb help. First, “30m” or “3 bar” is fine for handwashing, splashes, and maybe rain. Don’t swim with this watch unless the manufacturer confirms it’s OK. Next, “50m” or “5 bar” is OK for light swimming but not diving. With a rating of “100m” or “10 bar,” a watch is suitable for swimming, snorkeling, and daily wear without worry. This happens to be the minimum requirement for a dive watch. Finally, at “200m” or “20 bar,” you’re in the territory of professional dive watches.

Remember, though, that seals degrade over time. Gaskets dry out, crowns wear, and case backs lose compression. If water resistance matters to you, have the watch pressure-tested during servicing. It’s key that if you regularly take your watch into the ocean or the pool, you get it pressure-tested roughly once a year. I am the first to admit that I don’t strictly stick to this rule, but usually try to do this every 18 months or so. This helps indicate if the seals are intact and functioning as they should.

Concluding thoughts

Water resistance is one of the most misunderstood aspects of watch specifications. The numbers look scientific, but without context, they can lead you astray. IWC Schaffhausen stands out because it explains that difference — bars, not meters, and guidance on what each rating actually means. Compare that to other brands, and you start to see why two “30m” watches don’t behave the same when wet. As with most things in watchmaking, nuance matters. Next time you’re eyeing a new piece, don’t just check the engraving on the back.

Instead, read what the brand says about it. If you’re planning to swim, choose a watch designed for it. And if you’re heading into the sea, reach for the Aquatimer, not your 30m-rated dress chronograph. Remember, when in doubt, get your watch tested at your local watchmaker!