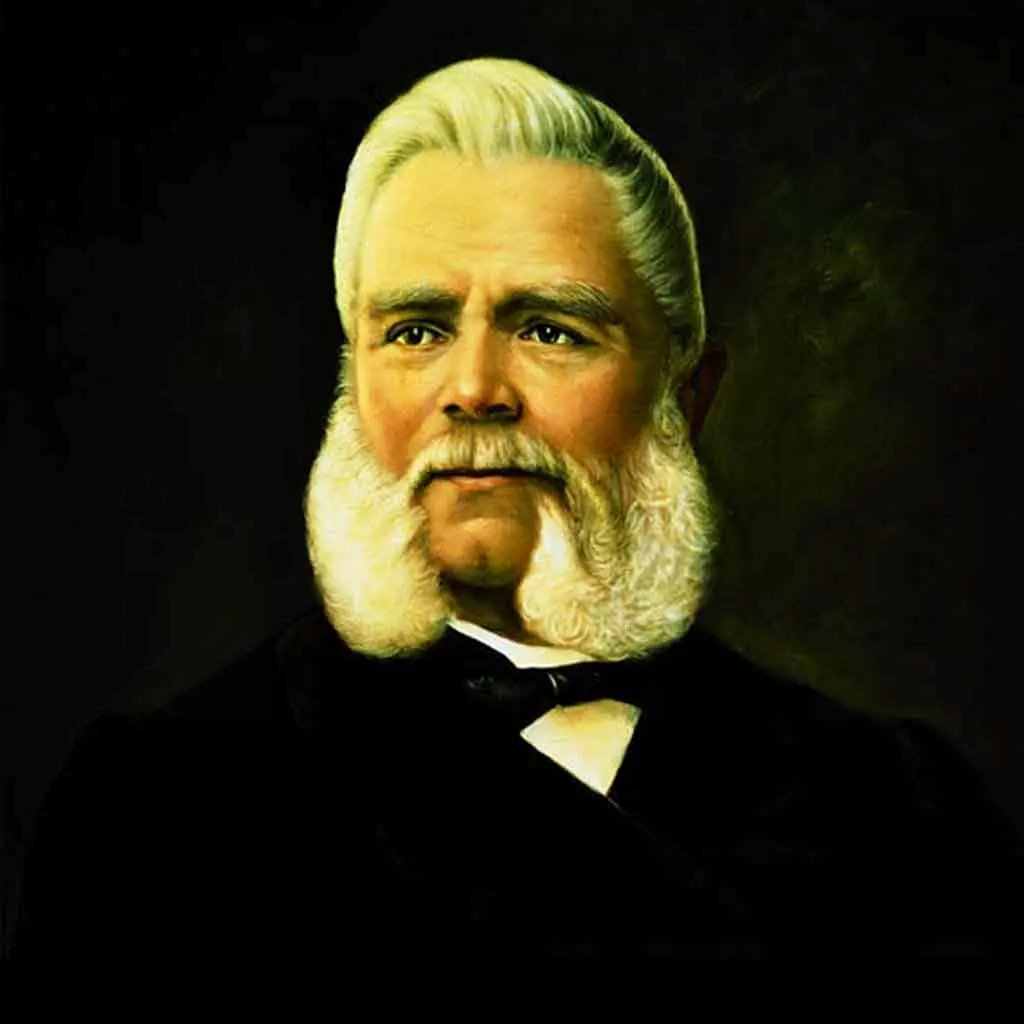

Who Was Jean-Adrien Philippe? The Story Of The Watchmaking Half Of Patek Philippe

La Bazoche-Gouët is a small town in the French Loire Valley. Today, roughly 1,215 people live there. In 1815, the number of inhabitants could have been a bit higher or a bit lower, but it’s safe to say that La Bazoche-Gouët was never a bustling hub of activity. It is a beautiful spot, though. The Loire Valley is known for its historic towns, including Orléans and Tours, as well as its world-famous castles, such as the Château de Chambord. The region, also called the “Garden of France,” is renowned for its fertile landscape. When Jean-Adrien Philippe was born in La Bazoche-Gouët, his destiny could have been to become an artichoke farmer. Despite that, because his father was a watchmaker, he also became one — an illustrious one whose name is still associated with the most prestigious brand in watchmaking, Patek Philippe. But who was Jean-Adrien Philippe?

The Loire Valley is a fertile place. There are plenty of vineyards, as well as artichoke and asparagus fields, that stretch along the riverbanks. Apparently, it’s also a breeding ground for gifted watchmakers. Jean-Adrien Philippe came into the art of timekeeping through his father, a skilled country watchmaker who had built several clocks with original and complicated movements. Young Jean-Adrien grew up among these and other clocks, and it gave him a deep understanding of horology. Maybe the town wasn’t big enough for two watchmakers, or maybe there was a burning ambition within Jean-Adrien; we don’t know. But we do know that, at 18 years old, he set off across Europe to refine his craft. It marked the beginning of a remarkable horological journey that would bring him worldwide fame.

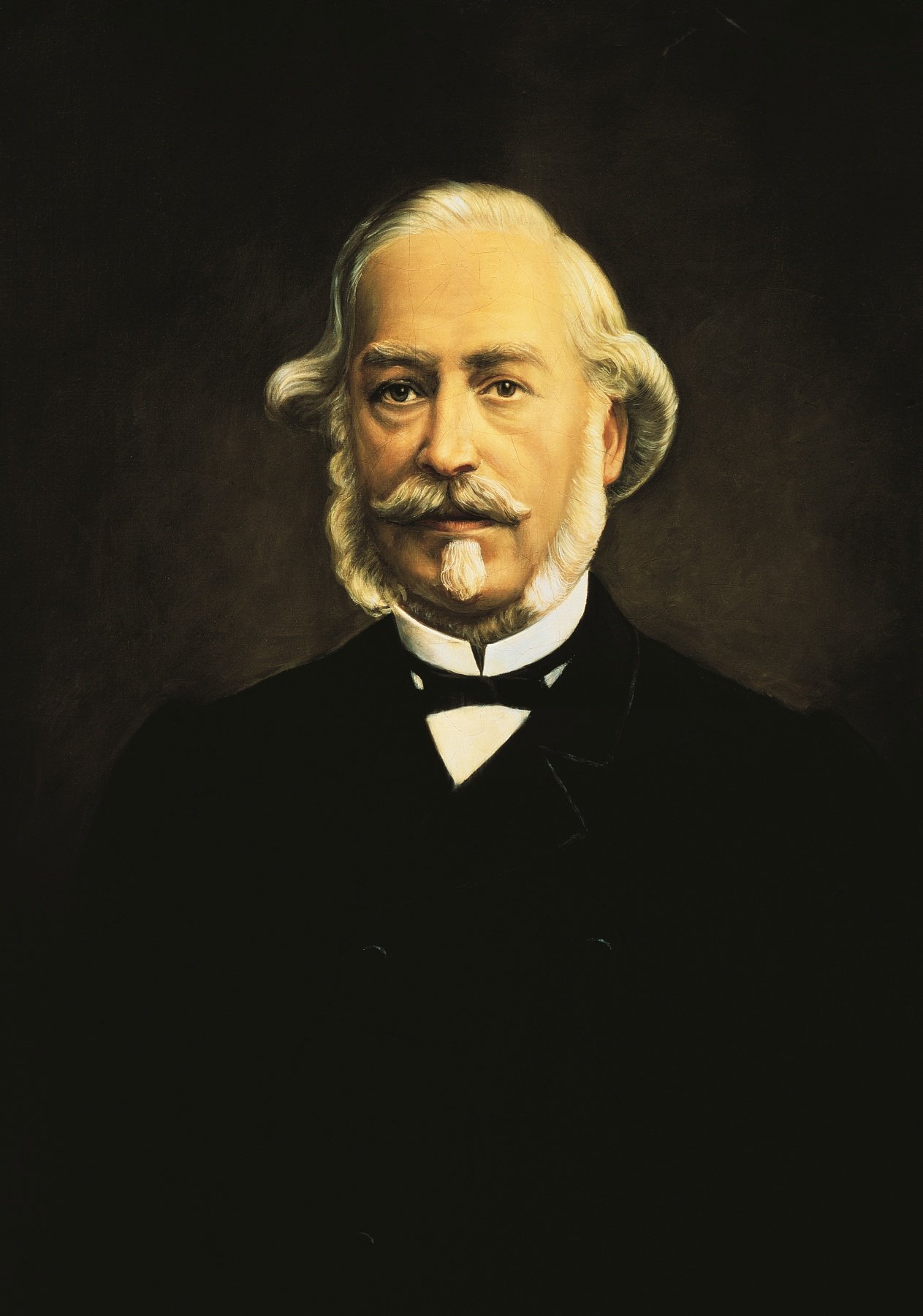

Who was Jean-Adrien Philippe?

Jean-Adrien Philippe traveled through France, Switzerland, and England before eventually settling in Paris. By coincidence, he arrived just as a government-funded factory for pocket watches was opening in nearby Versailles. Inspired by masters like Breguet, Berthoud, and Le Roy, Philippe aspired to earn a place among the great Parisian watchmakers. On his travels, he met a young Swiss watchmaker in London, and they partnered up to launch a business that soon produced up to 150 watches annually. At the age of 25, Philippe built his first self-designed movements, and he also began exploring a revolutionary idea that would come to fruition in 1842 — a method for winding a pocket watch and setting its hands without a key.

How and why did young Philippe come up with the concept of keyless winding and setting? We can only guess, but Fratello has a theory. It’s based on the premise that people living in the 19th century are much the same as we are living two centuries later. The average person today misplaces up to nine items a day, according to a recent Lostings Lost and Found Statistics report. It reveals that in the United States alone, over 400 million items are reported lost and found each year. Among the most commonly misplaced belongings are wallets, phones, and keys.

And there you have it — keys. People often misplace various types of keys. In the time of Philippe, they excluded the car key, but they probably included the key of the pocket watch. Perhaps Jean-Adrien was tired of losing his pocket watch’s key repeatedly and decided once and for all to eliminate the object and, thus, the problem. It’s a plausible, practical, and very human hypothesis, don’t you agree?

The invention of the winding crown

In any case, Jean-Adrien Philippe worked on a system that would eliminate the need for a key to set and wind the pocket watch. His research culminated in 1842 with the creation of a stem-winding system that he would later describe as “a simpler, more solid, and more convenient system than has ever existed before.” The importance of the invention was immediately recognized — further proof that losing the key to the pocket watch was a problem suffered by many more than just a frustrated watchmaker. In fact, the keyless winding system earned a bronze medal at the 1844 Industrial Exposition in Paris. That event marked a turning point in Philippe’s life and career because his invention attracted the attention of a man with the last name Patek.

How Patek met Philippe

Antoine Norbert de Patek (1812–1877) was a Polish independence fighter and political activist who fled his country after a failed uprising against Russian rule. He fled to France, but Russian diplomatic pressure made him leave for Switzerland. After trading in liquors and wines, he met with Franscizek Czapek, another exiled Pole and also of Czech descent. Czapek had worked as a watchmaker in Warsaw, and together, he and Patek set up a watchmaking business. The small firm Patek, Czapek & Cie. employed only about half a dozen craftsmen and produced roughly 200 high-quality watches each year. It seemed like a match made in heaven, but the two founders’ characters clashed.

Growing tensions between Patek and Czapek eventually led to Czapek’s departure. Eventually, in 1851, he founded Czapek & Cie., where he continued producing watches until 1869. However, his departure a few years earlier had left Patek searching for a watchmaker to continue Czapek’s work. And during the 1844 Industrial Exposition in Paris, he found the perfect man for the job. On the 15th of May, 1845, the position left vacant by Czapek was filled by the 30-year-old Jean-Adrien Philippe.

A closer inspection of the winding crown

The crown on your watch is an object taken for granted. Most likely, that’s because it’s so widespread. Whether you’re an Omega fanboy or a Hublot aficionado on the opposite end of the watch spectrum, you have the winding crown in common. However, the fact that we all use the rotating pull-out button known as the “crown” says a lot about the gravitas of Philippe’s invention. It’s everywhere, and since its inception in the 19th century, it has undergone hardly any changes.

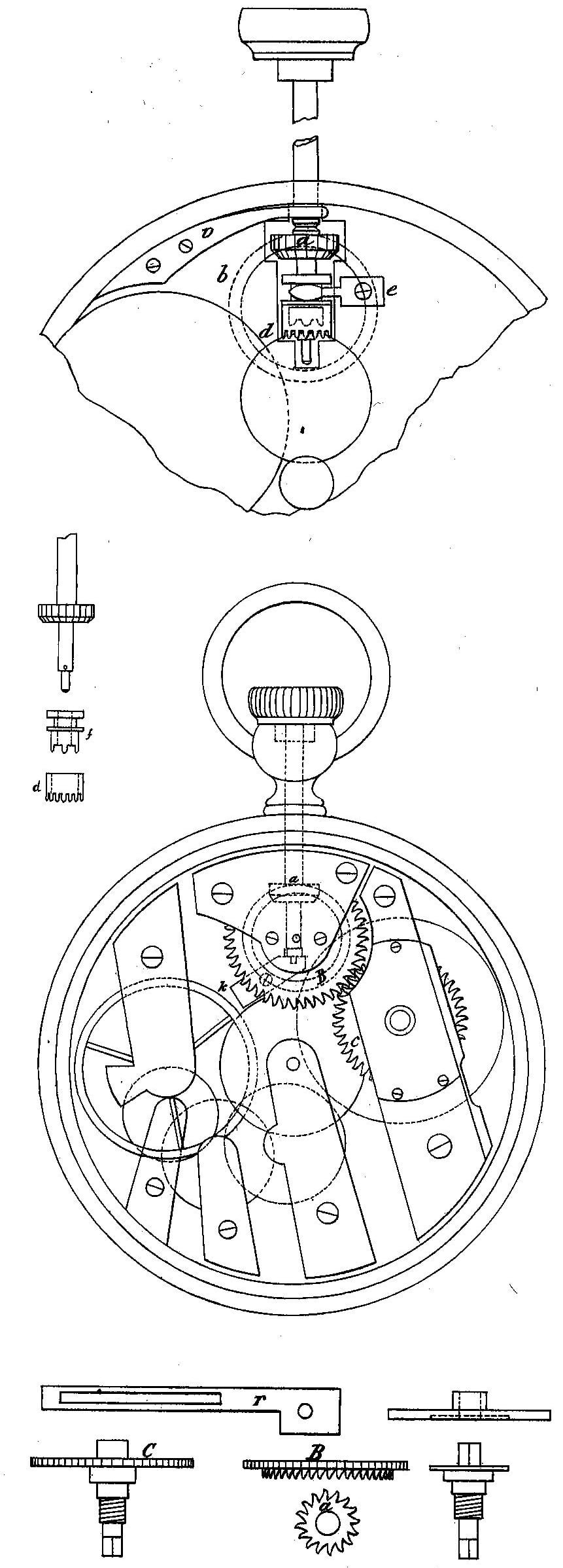

The system Philippe presented during the French Industrial Exhibition had all the features of the crown as we know it. In its resting position, the mechanism allowed the movement to be wound; when pulled out, it enabled adjustment of the hands. A small steel cylinder, able to slide along the square-shaped winding shaft, sat on the axle. Each end of the cylinder had gearing that alternately engaged for winding or for setting the hands. A rocker mechanism ensured that when the crown is pulled out, the cylinder disengaged from the winding system and switched to hand-setting mode. Pressing the crown returned it to its original position.

In 1863, Philippe introduced and patented an evolutionary breakthrough — the “slipping” spring. This clever mechanism ensures that a watch’s mainspring cannot be overwound either by the crown or a self-winding system, a fundamental feature of the automatic (self-winding) wristwatches we wear today. By that time, Jean-Adrien was already one of the name givers of Patek, Philippe & Cie.

Pocket watch signed “Patek, Philippe & Co., Genève,” movement no. 80050, case no. 203910, manufactured in 1888. This was the personal watch of Jean-Adrien Philippe and his son, Émile, who took over his father’s position after he died on January 5th, 1894. Émile had the watch engraved with his father’s name and date of death. — Image: Christie’s

Working at Patek, Philippe & Cie.

Some say the system for winding and setting is called a “crown” because he modeled it after the crowns seen on the heads of Europe’s many kings and queens. However, since Philippe was a watchmaker, the form-follows-function theory seems more valid. He wanted something round that offered a good grip for turning, and what he created coincidentally resembled the lavish “hats” royals put on their heads during special occasions. In the eyes of a watch fan, Philippe’s crown is the one crown that rules them all.

Antoine Norbert de Patek also thought so because, although he was not a technician, he was a perceptive businessman who immediately recognized Jean-Adrien Philippe’s talent. He quickly invited the inventor of the crown to join his firm — the future “Patek, Philippe & Cie. – Fabricants à Genève” — and Philippe accepted a few months later.

The movement inside Jean-Adrien Philippe’s pocket watch offers a view of his famous invention, the keyless winding system — Image: Christie’s

One revolution causes another

Soon after Philippe joined Patek, the French Revolution of 1848 disrupted business. It forced the company to use the slowdown as an opportunity to introduce mechanized production. Following the example set by Georges-Auguste Leschot at Vacheron & Constantin eight years earlier, and with the support of skilled technicians, Philippe developed machining tools capable of producing fully interchangeable parts. However, these efficient new methods did nothing to dampen his inventive spirit. During this period, he created some of the company’s most remarkable movements. For instance, he invented the aforementioned slipping spring, a compensation balance, several index assemblies, and winding stems designed for easier assembly.

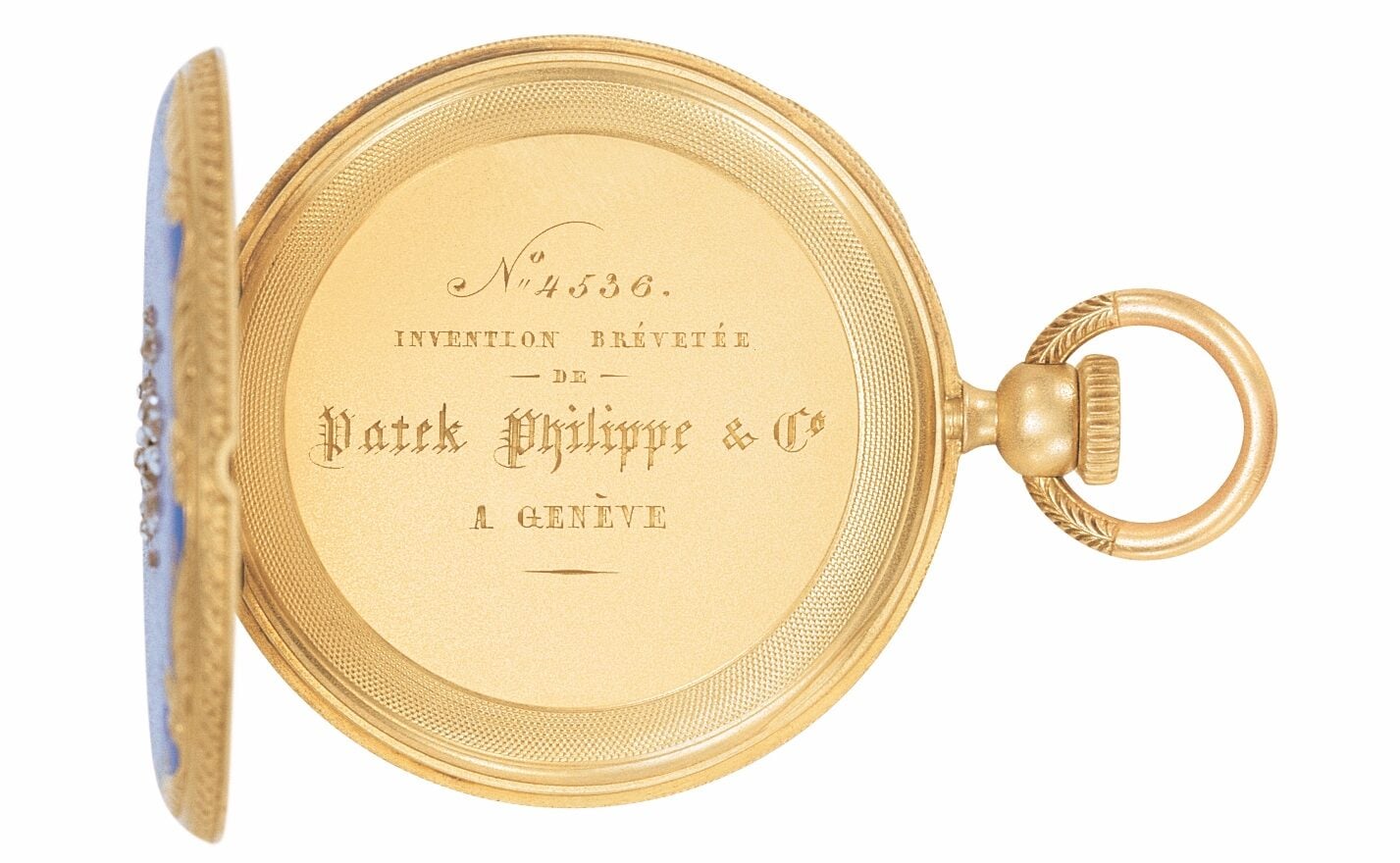

The pendant watch said to have belonged to Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland — Patek, Philippe & Co., Geneva, No. 4 536 (ca. 1850/51) with open face, keyless winding and setting, yellow gold case, fluted case band, white enamel dial with black painted radial Roman numerals, blued steel “Breguet” hands 13-ligne movement, ébauche from the Patek Philippe workshops, gilded, with cylinder escapement, monometallic balance, and flat blued steel hairspring

More than a watchmaker

Patek was confident Philippe’s involvement would take his business to new heights. He was right. Soon after moving to Geneva in 1845, Philippe joined Patek’s watchmaking endeavor as a partner and technical director. In this new position, Jean-Adrien’s technical genius came into full bloom. So, in 1851, Philippe’s pivotal role was recognized through the name change from “Patek & Cie.” to “Patek, Philippe & Cie.”

As the company’s technical director, Philippe oversaw manufacturing, refined production methods, and drove the development of new features and innovations. Advancing technical boundaries was his greatest passion and the area in which he truly excelled. At first, he focused on perfecting his pioneering keyless winding systems. This endeavor saw him secure several patents for his distinctive winding and hand-setting mechanisms. He was also deeply involved in the demanding craft of chiming timepieces. The company was already producing watches that struck the quarter hours. Soon after Philippe arrived, its first true minute repeater debuted. Philippe’s later contributions played a vital role in early milestones of horology, including the advancement of self-winding movement technology.

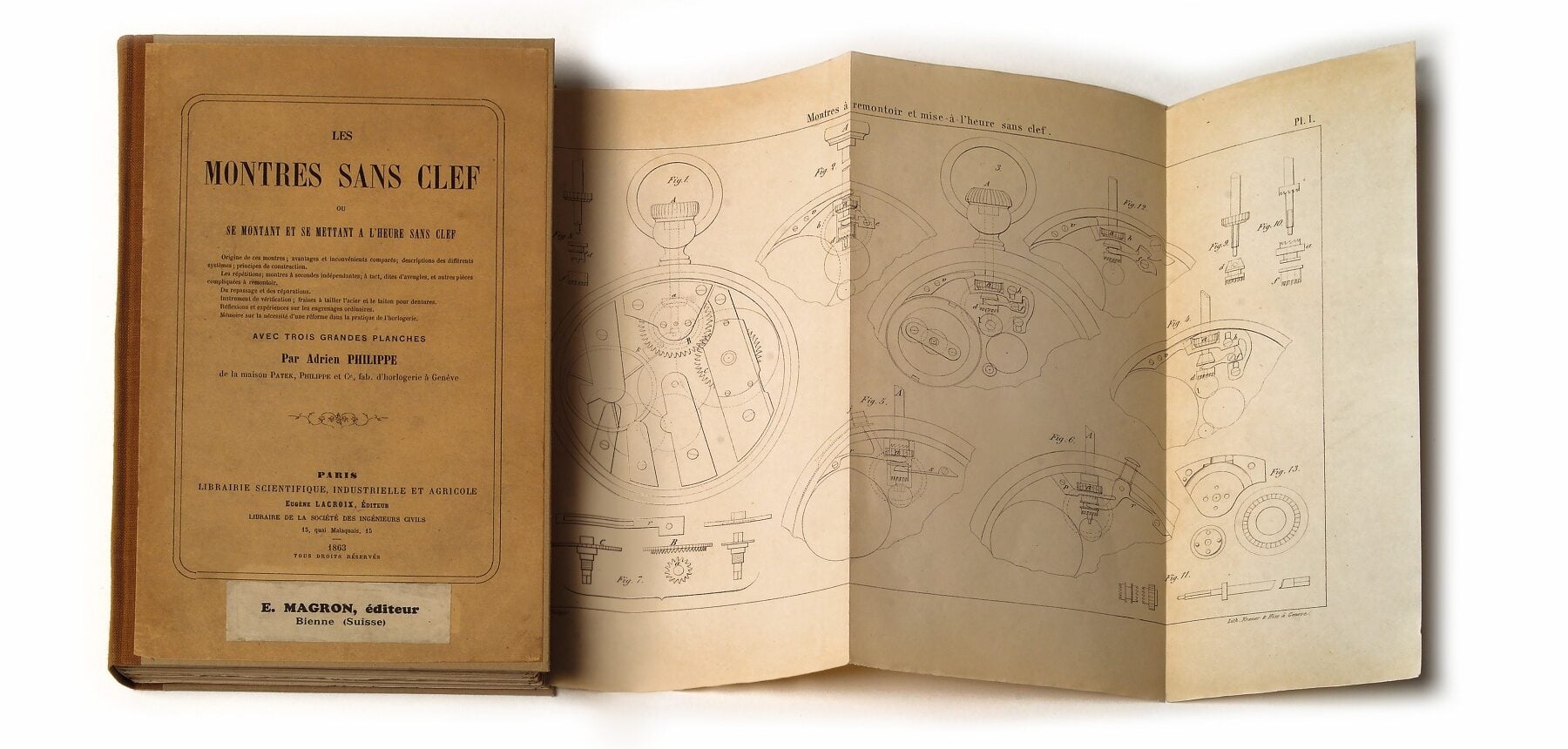

Beyond his mechanical achievements, Philippe also made significant contributions to the watchmaking field. He did so through his writings and by publishing studies on topics of interest to watchmakers. As you would imagine, his writings include a book on keyless winding, which was published in 1863. In recognition of his work, the French government awarded him the Legion of Honour in 1890.

The “magic” between Patek and Philippe

The combination of the watchmaker Philippe and the businessman Patek worked because each of them focused on different fields. But when those two fields came together, something extraordinary happened. Patek concentrated on the famous decorative aspects of Genevan watchmaking that had first captured his heart. He hired highly skilled artisans to adorn Patek Philippe watches using time-honored crafts, like enameling, engraving, guilloché, gemsetting, and marquetry. This marked the beginning of a tradition that remains alive at Patek Philippe to this day. And when combined with complicated movements, which Philippe laid the foundation for, timepieces of historical value emerged, helping Patek Philippe become the revered brand it is today. The powerful partnership between Patek and Philippe was the deciding factor in their company’s monumental success.

Ref. 992/187G-001 “Lake Geneva Barque” pocket watch in white gold with flinqué enamel and miniature painting

Philippe lives on

Jean-Adrien Philippe could have been an artichoke farmer who frequently lost his keys. Instead, he became a watchmaker who invented the winding crown. This most remarkable invention is now used by roughly 99% of the mechanical watches currently in production. In 1891, the year after the French government awarded him the Legion of Honour, he retired from Patek, Philippe & Cie. He passed his responsibility to his son, Émile. Just three years later, Jean-Adrien Philippe died. But his legacy lives on today at Patek Philippe, where more than 100 patents have been filed. And every Patek Philippe watch uses a crown.